Jennifer Thomas

Library and art

Till a few years ago, I didn’t think much about a connection between library and art. Being part of a community of library educators has helped me discover the natural connection between art and reading, vis-à-vis, common elements like imagination, creativity, and pictures. In his seminal study of children’s drawings, John Matthews* showed that there is a relationship between thought and drawing. Drawing and other forms of visual arts support a movement from simple, spontaneous concepts to more complex ones and enable higher cognitive functions. This organic movement is lost when drawing in schools is limited to imitation, repetition, and filling in colours. In this article, I describe my experience of participating in a professional development program that was designed to enable library educators to integrate art more organically in the library.

This experience enabled me

– to help children look at art without getting intimidated,

– to support children to create their own authentic art,

– to extend and deepen reading experiences using art.

The Mehlli Gobhai Workshop series was offered online by Bookworm, Goa to educators in April 2022. It had the artist, Mehlli Gobhai’s The Tree Book$ as the central artefact, which inspired us to look at nature closely and design our own tree books. Facilitators from 11 organizations across India met online for six sessions with the Bookworm visual arts educator, Sanika. During this time, we experienced what it meant to look at abstract art, talk about it and finally create nature inspired art, ourselves. Sanika would in part model, and in part, guide us on how we could conduct these sessions. Lesson plans were shared with us that helped take these sessions forward with children, leaving enough space for adaptations and flexibility to work in our contexts.

When we took this to the children, all the sessions were located within the space of a functioning library to integrate books, reading, and art. Books were an important part of each session. There were book talks, book games, and book borrowing. The idea of making tree books started with a shared reading of Mehlli Gobhai’s The Tree Book.

The library I work in is located in a private unaided English medium school in a suburb of Mumbai. The school follows the Maharashtra state board curriculum and it has an active library program that is inspired by the idea of an open library (Mukunda, 2006). Prior to this, I had taken an interest in bringing art closer to children through the Self Development and Art Appreciation Course which the Maharashtra state curriculum had prescribed for classes IX and X. With the course scrapped in 2021, this workshop gave me an opportunity to learn another way of bringing art to younger children.

Children and art

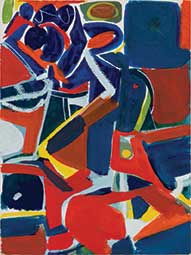

When I took a few of Mehlli Gohbai’s abstract paintings to my children (9-12 year olds) on the first day, they hesitated to accept the work as art. For most, it was the first time they were looking at and responding to abstract artwork. Slowly, some said the paintings represented

“Mess”

“Confusion”

“Sadness”

By holding back my comments and giving children time to respond, some even saw objects hidden as symbols!

As we proceeded to make our own abstract paintings, there was hesitation to make the first mark on the paper. Encouraging children to work directly with colours helped. The approach is to limit the use of pencils, which invariably leads to the use of erasers.

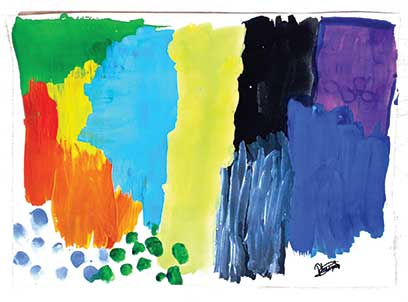

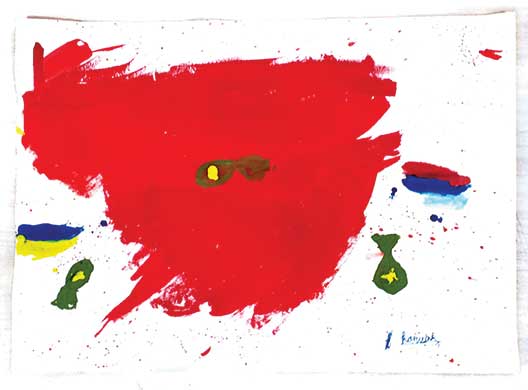

Sharing my art and talking about it helped children think about how they could get down to making their own artwork. They listened intently. They thought carefully. They were provoked to look inside themselves. Deep personal connections were evident in what they painted.

Dhwani: I’ve tried to show my life through the pandemic and now…these colours show how we all suffered a lot and now brightness and happiness is coming back into our lives.

Kanishk: I’ve drawn the Ukraine – Russia war and the dots show the many lives that have been lost.

Rikhav: Sometimes I wonder how our eyes see so many colours. I’ve tried to draw an eye…seeing all the colours.

It is worthwhile to note that the workshop was happening in the context of still fresh memories of the COVID-19 pandemic and they had not yet resumed regular face-to-face schooling. This was a voluntary summer workshop. The Russian attack on Ukraine in March-April 2022, dominated the news with prominent images of loss and destruction. To a certain extent, the choice of their colours reflects the heavy and negative emotions (fear, death, uncertainty) they were probably experiencing. As an educator, it was revealing to me how reality mediates children’s art and how important it is for facilitators to enable unfettered expression by creating a safe environment. The library was a perfect ally for this as children recognized it as a space, different from that of their classrooms – safe and comforting.

Later, children shared how they were worried and apprehensive on the first day as they didn’t think of themselves as artists. But as the sessions went on, some things changed. Looking at artworks by popular artists with their peers led to talk and discussion which otherwise rarely find space in the conventional classroom. Artworks such as O’Keefe’s Lawrence Tree, Mitchell’s Trees III and Carnegie’s Black Square generated much discussion on perspective, colours, and lines.

There was another thing that helped, which I realized only later. One day Bernice told me, “When you came and saw my tree painting and said “WOW”, I really felt happy. I felt like I could really paint well.” As facilitators, sharing genuine and positive feedback with students as they create their artwork is crucial.

The last three sessions were held in a public garden. The experience of identifying a tree to illustrate, to observe, to wonder, and research and plan the pages of a book, was a joyful and stimulating experience. Arnav noticed mangoes overhead, a butterfly sat on Angel’s nose, Kanishk imagined the tree against the night sky, Dhwani used Google lens to find out more about her tree. The sense of freedom and responsibility this act of slow looking, choosing, and deciding brought was new for most. At the end of the five-week long workshop, seven tree books were created and each one was a fascinating story world in itself.

Reading and art

In our day-to-day practice in the library, we now try to integrate art in other simple ways. Art integration serves many purposes – motivating reluctant readers to read, improving reading comprehension and even fostering critical thinking skills among children (Jordan and DiCicco, 2012).

This experience taught me that we can include art at different points in the reading experience. Here are some ideas:

• Showing a painting or photograph before we enter a story text is a good way to help build background knowledge.

E.g., Before reading Michael Morpurgo’s war story Our Jacko, we spent time looking at the title page, observing the illustrations and slowly building our schema around a possible war. Later we watched a video on World War I.

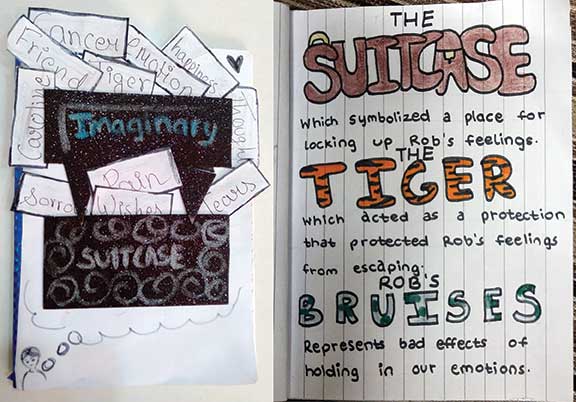

• Illustrating metaphors helps children think more deeply about the story and make connections as they read.

E.g., While reading a risky text about grief and loss, children thought about symbols in Kate DiCamillo’s novella, Tiger Rising. Here is an example of how readers made sense of the many symbols in the story through art.

A few years ago, it was hard for me to see such a deep connect between art and reading. I have now come to realize that integrating art in the library can lead to many exciting new outcomes, building empathy and critical thinking among children, motivating reluctant readers to read, and enabling collaboration between children. In our library, this journey has just begun and we remain hopeful that it will lead to many more children becoming discerning readers of the word and the world.

References

• DiCamillo, K. (2001). Tiger Rising. Candlewick Press.

• Gobhai, M. (2020) The Tree Book. Talking Cub.

• Jordan, R.M. and DiCicco, M. (2012) Seeing the Value: Why the Visual Arts Have a Place in the English Language Arts Classroom. Language Arts Journal of Michigan: Vol. 28: 1, 27-33. https://doi.org/10.9707/2168-149X.1928. https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1928&context=lajm

• Matthews, J. (2003). Painting in Action. Drawing and Painting: Children and Visual Representation. London: Paul Chapman Publishing.

• Morpurgo, M. (2014) Our Jacko. Walker Books.

• Mukunda, U. (2006) The Open Library. Bangalore: Centre for Learning. https://archive.org/details/TheOpenLibrary.

*Artist and educator who has worked with learners of all age groups from nursery to university. He wrote extensively about the origin and development of visual representation, expression, and symbolism in early childhood.

$A wordless picture book from India which tells a beautiful story through striking paintings of nature.

The author is an educator with a deep interest in libraries and reading enabled through her work at Sharon English High School, Mumbai and Bookworm, Goa. She can be reached at jennifer.ktg@gmail.com.