Indu Nair

In this article, I want to reflect on my experiences of building a library and its collection as windows and mirrors, the challenges faced while doing so in a diverse library community, and the steps I would like to follow to address these challenges. Before diving in, I’ll begin by providing a quick background of windows and mirrors as a concept.

Emily Style introduced the concept of school curricula serving as “mirrors and windows”1 – mirrors to help students see themselves and their lived realities, windows to see the same of others. Windows could also help them see, and possibly appreciate, more than just differences; they could also see their shared humanity! The Library Educator’s course, offered by Bookworm, Goa, introduced this very concept, in the context of libraries and good, diverse library collections – collections that offer readers both “mirrors and windows”.

I confess I was immediately drawn to this seemingly simple, yet beautiful idea. Partly because I realized what a validating and life-affirming experience it could be to see yourself, your lived reality in a book (i.e., a mirror); but also because I suddenly saw the immense potential that library spaces had to foster and cultivate empathy and understanding – traits that are especially vital in an increasingly troubled and polarized world. The concept of “windows and mirrors” has stayed with me since, but no longer seems as simple as it once did. A continued engagement with Bookworm, Goa, and my own budding experience in the library, have instead added further layers of nuance and complexity to the matter, and for that I am glad.

For one thing, it has become increasingly clear that diversity in the library doesn’t just exist in our collections – nor should it! It does and should exist in our library users (and library educators) as well. This diversity exists in our communities at large, and in school libraries, at the very least, in the parents and families of our library users. This very diversity has left me with one question: How does one consciously and actively build a library space and a collection that acts as “windows and mirrors” for readers, while also being aware of, and sensitive to, the concerns, discomforts, and anxieties of library users and their larger community? Two books that come to mind are Guthli Has Wings by Kanak Shashi, and Friends Under The Summer Sun by Ashutosh Pathak. Both stories capture aspects of childhood, while sensitively portraying the lives of characters who may be transgender. Both stories gently and honestly introduce windows and mirrors vis-à-vis gender identity. Similarly, there are stories that create windows and mirrors along other axes of diversity, including, but not limited to, religion, caste, class, disability, body positivity, sexual orientation, race, etc. While these books are valuable additions to any children’s libraries, I can see some members of school communities in general feeling uncomfortable with their presence in libraries. As a library educator who believes in the importance of “windows and mirrors”, how do I hold space for any discomfort resulting from my not compromising on a good, diverse collection? It is a question that I see myself grappling with in my ongoing work as a library educator.

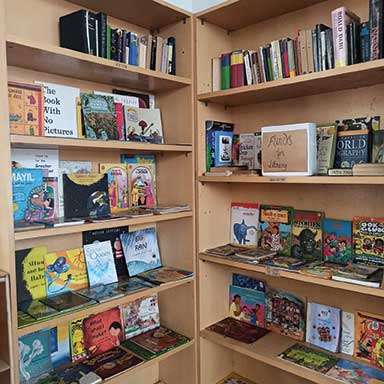

Windows and mirrors in Bidiru Learning Centre’s library

At Bidiru Learning Centre, compassion and empathy are two of several core values central to our approach to education. Unsurprisingly, they are prioritized and reflected in different learning spaces, including our library. The concept of ”windows and mirrors” plays a large role in this: from the way our team curates our library collection (trying to capture diverse voices and experiences), to the ways in which we engage with our books – pre and post-read aloud activities, discussions, etc. This was true even when we were operating primarily in the online mode, as we were trying to curate a sizable collection of physical books and had to depend more on online sources like Story Weaver. In addition to focusing on developing our students’ love for reading for pleasure, we tried to use the “windows and mirrors” concept as a lens to help us select good stories. The concept has even lent itself to discussions around human libraries, exploring questions such as: “If I could borrow a human book, what/who would I ‘borrow’?”, and “If I were a human book, what would my title(s) be, what would my stories be about?”

Of course, all this needs to be done without becoming preachy; without taking away from the joys of reading and exploring stories. After all, the objective is not moral education, but to help the reader develop a love for reading for pleasure, while exploring and connecting to different worlds and realities through “windows and mirrors”. This needs to be kept in mind while picking titles, designing activities and leading discussions.

For instance, how does one open up for discussion a rich, beautiful story that involves characters who are transgender, without imposing a moralistic agenda? I tried to navigate this when I read Friends Under The Summer Sun with a small group of students at Bidiru Learning Centre. Post-read aloud, I asked a few open-ended questions to gauge how much had been understood, and how the students felt about what they had read. I was mindful to leave space for the children to express any discomfort – and one child did (“Oh God!”), open to letting the discussion flow, responding accordingly, allowing the peer group to respond to each other, and ready (to the best of my abilities) to answer questions if any were asked.

Similarly, our entire team tries to keep this in mind when picking up titles for the library2. We try to avoid stories with a clear-cut moralistic takeaway3 and instead look for stories that are engaging, meaningful, and enjoyable, and also add to the richness and diversity of our library collection. Happily, there is a treasure trove of children’s literature to pick from – thanks to some increasingly conscious efforts to publish stories that reflect voices and lived realities otherwise poorly heard or not heard.

Opening windows for those only seeking mirrors

As resolutely convinced as I am about the need for, and beauty of, libraries and their collections serving as “windows and mirrors”, I understand that there are those in this diverse community who may have their reservations. In an increasingly polarized world, there are those who only want to see mirrors, only want library collections to reflect their lived realities and world views. Quite often, these are people who benefit from maintaining the status quo.

These reservations are admittedly trickier to tackle because they’re more connected to individual and sometimes societal concerns, discomforts, and anxieties. Sometimes they require multiple discussions, potentially uncomfortable conversations and deep dives or reflections on everyone’s part – library users, library educators and extended communities included. Sometimes they challenge long held views or hidden biases that maintain the status quo. Sometimes they may even lead to conflict – at the very least, conflict of ideas if not personal conflict. While I don’t believe this is negative, I fully acknowledge that it can be tricky and uncomfortable – especially for someone who can be somewhat conflict averse. The question of how to navigate these waters is both fascinating and potentially nerve-racking.

How do I, as a library educator, open windows for them?

There was a time when I thought the answer was clear: convinced about “windows and mirrors.” Stand your ground. That’s all. I thought it was an all or nothing situation. Then, at an event organized by Bookworm, someone raised a similar question, and the response they got blew my mind. Effectively, it was to stand your ground in terms of “windows and mirrors”, but take your community with you. Move with your community – library, school, or extended. As I understood it then, be open to having those conversations and dialogues. The more I think about it now, the more I see it also involves holding space for people, and their discomfort and their anxieties – at least in conversations with them. Perhaps encouraging them to sit with their discomfort a little, as I might sit with mine, to try and understand it more. Acknowledging their right to feel the way they do, while also refusing to let their discomfort dictate what happens in the library – especially if it dilutes the practice of “windows and mirrors”. While I sincerely hope to be able to do this in my practice as a library educator, I acknowledge the following:

i) I desperately need more practice in the above – the more I do this, the more insight and understanding I can gain on this question.

ii) This need not always be a linear journey of progress. Removing that expectation of myself might actually better help me navigate this question.

iii) I may not always have the bandwidth to do the above, and that’s ok. My mental health is important too.

iv) This does lead to the larger question about if and where library spaces draw the line – especially in the face of bigotry, fear, or even hatred.

- “If the student is understood as occupying a dwelling of self, education needs to enable the student to look through window frames in order to see the realities of others and into mirrors in order to see her/his own reality reflected. Knowledge of both types of framing is basic to a balanced education which is committed to affirming the essential dialectic between the self and the world.” – Style, Emily. Curriculum as Window and Mirror, 1988.

- Illustratively, some of the titles we have picked so far include Head Curry by Mohammed Khadeer Babu, Wings To Fly by Sowmya Rajendran, Ismat’s Eid by Fawzia Gilani Williams, Red. A Crayon’s Story by Michael Hall, Bhimayana. Experiences Of Untouchability by Srividya Natarajan and S. Anand, Mother steals a bicycle and other stories by Salai Selvam and Shruthi Buddhavarapu, and more.

- Moralistic takeaways aren’t always stated outright, i.e., “the moral of the story is” – sometimes it’s found in the tone of the story, which can be harder to spot.

The author is a library educator on her learning journey at Bidiru Learning Centre, Bengaluru. She can be reached at indu.indesha@gmail.com.