Sujata Noronha

We inhabit a complicated world. There is likely to be very little argument with this statement. So, it is not surprising or startling to recognize that the library space as a place is unlikely to be free of complications. Yet the word library continues to play out in images and contexts – probably sepia toned, of quiet contemplation, serene environs and ideas in texts that belong to the romantic period of literature. Rarely, if ever, does the word library conjure up a space of pop colour, noisy reverberations, play, pondering, disquiet, provocations, and tension. Yet, for over a hundred of our sister library educators in this country, we are nudging such complications – compelling ourselves and others to have big conversations in the library, to take risks and to reimagine what the potential for library work can enable. These risks include questioning the dominant narrative around idyllic childhoods, pushing back against the idea that the library is a place of only light fun and recreation as well as risks along the lines of questioning the very existence of libraries as reproducing knowledge streams that may be hegemonic, dominant, and oppressive to many people. These are not merely acts of resistance, which they are but are also some of the ways in which a library responds to complications it knows are out there in the world “… in the endless cycle from destruction to greatness, libraries have always recovered: it is in our nature to leave our own stamp on society.” (Pettegree, A., Weduwen, A. d., & Barrett, S, 2021).

We need to reflect and act on the library as a place that responds to the complications of the world in order to be relevant and progressive.

In 1931, SR Ranganathan bequeathed the ‘Five Laws of Library Science’ to the domain of library work. He recounts that the origins of these five statements were arrived at by intensely studying, applying, and reflecting on the activities of librarianship prevalent at the time. The time was the late 1920s, colonial India moving towards an independence movement, dominated, at least in the newly forming library sciences, mostly by upper caste men who were renowned scholars in the ‘sciences’. Was this too a complicated time? It really depends on whose point of view, you choose to hold, but the reality is that there can hardly be a time in the Anthropocene that is not complicated. Yet, library work which was distilled almost a hundred years ago to a positivist frame – articulated simply and attractively in five statements, continues to be interpreted unimaginatively. The laws, written as five statements, exist for our interpretation and imagination. And, the space of children’s libraries, within schools and communities, has remarkable potential for complication if we agree to big conversations.

The fifth law of library science states, ‘The library is a growing organism’ and for a long-time growth has been interpreted mostly in terms of the collection of library materials – numbers, varieties, relevance, form and such – and to some extent, space and staff are also elements of growth in the interpretation of the fifth law. But in a world that is rapidly shifting, merely relying on ‘countable’ items cannot be considered growth for the library. Ranganathan writes, “Unlike the other four laws, the fifth law invites our attention to the fact that the library as an Institution has all the attributes of a growing organism. A growing organism takes in new matter, casts of old matter, changes in size and takes on new shapes and forms” (S R Ranganathan, 1931)

Tired by Langston Hughes

I am so tired of waiting

aren’t you,

For the world to become good

And beautiful and kind?

Let us take a knife

And cut the world in two –

And see what the worms are eating

At the rind

The library as a responsive organism demands that we ‘bring in’ new matter not always in physical ways but in our attitudes, conversations, and attempts to meet the complications of our time. This is a time for reconsideration of who holds power in the library, what we have privileged as knowledge, whom we have elevated, whose voices we are reproducing, what do we imagine is a real childhood versus a ‘romantic’ one, and what spaces do we want to attempt to create – to enable a new, more just order.

Many of us are socialized around touch as an act of love, rarely questioning the very condition upon which human survival depends from birth – yet work in the library with diverse groups of children showed me how extremely contentious this can be and how ill-prepared I was in the early years of my practice. The tension around hand-holding for example, in a circle game alerted me to the politics of touch that very young children learn from socialization. Children were not able to articulate the why but they knew the how and their hesitancy to touch enabled me to recognize the importance of talking about touch. I was at the time, not fully able to address this but I began by looking at my collection and had many wonderful affirming conversations using Why Are You Afraid to Hold My Hand by Sheila Dhir (Tulika, 1999) as a starting point that extended and includes Friends in School by Jhoopka Subhadra from Untold School Stories (Mango, DC Books, 2008) and other texts.

This kind of a re-imagination while not easy and comfortable is still possible in the library, irrespective of one’s own socio location but mindful of one’s privileges because the very identity of the library rests on the premise of inclusivity, openness, freedom, and equality. But each of those principles demands from us, the educators in that space, an examination and re imagination.

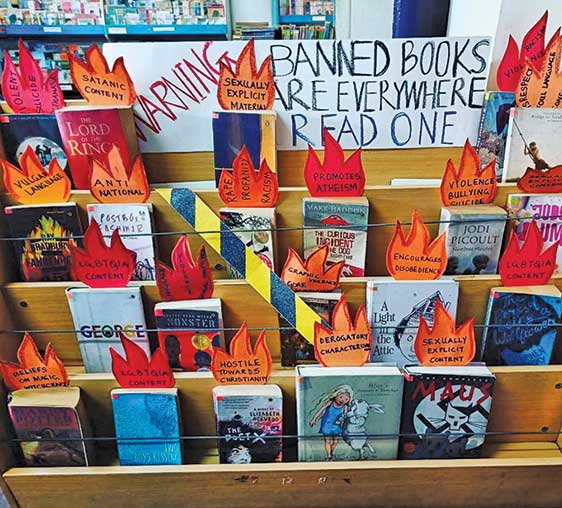

In the past few months, we have witnessed through media and for scores of people through direct oppressive acts of violence – inhuman actions. Do we continue to then only exhibit and promote romantic stories in the library and a space that is silent? Can we begin to be brave and create spaces to talk about social orders, who have voice, whose stories are shared and from what point of view? Can our collections begin to include non-dominant voices and formats and can we open ourselves to preparing for a brave new world?

In our practice we are repeatedly shown how ready children are to receive and enquire about complications and also how unprepared we are to face these. Often, when left to our own lines of planning in the library, we may unconsciously select topics and texts that stay far away from the complications of life around us. But children live in the real world and are very aware of these complications and often have questions about them. The library could well be that space of that imagination. It took a 13-year-old child’s question about ‘Falistine’ to open up many other questions in a small circle at the library and a consequent planning and offering on ‘Understanding Palestine through literature and poetry’.

Some other simple passive ways may be researching, sourcing, and sharing – media to watch – news clippings on notice/display boards that tell the same story from different points of view – links to podcasts and talk-shows that question dominant paradigms, printing out memes that may sharply remind us about matters at hand, and include humour and satire as powerful tools of resistance and questioning.

Some simple active ways may be

• Inviting persons who are keen to talk about matters of importance and creating a space for dialogue.

• Making a list of texts that could be read or put on the library wish list for the immediate future.

• Inviting children to make posters that communicate their feelings and positions and having a poster wall exhibition in a visible space.

• Responding to poetry that evokes a response in art that can be displayed.

Some engaged ways for the educator may be skilling yourself on how to begin and plan for ‘risky’ and big conversations through reading other practitioner blogs and reports, attending ongoing professional development workshops, or just talking and reaching out to fellow practitioners in the community.

Presently, library spaces for children are attempting to include diverse books and experiences that accommodate the rich, cultural habitus of our people, but too often these texts represent uncomplicated lives and are almost fearful of unbalancing a long-held hegemony on what children must read and engage with. At the same time, the world around our children is exploding with messages, information, and experiences that no one is prepared for. Can the library continue to be a refuge and a place of resistance – one that is also seeking answers and hope in our openness to explore these complications?

S.R Ranganathan, when explaining the Fifth Law concludes the chapter by writing, “…What further stages of evolution are in store for this growing organism – the LIBRARY – we can only wait and see.” (S R Ranganathan, 1931). In the first century of public libraries (around the 1880s) those who entered the library, “did share one vital characteristic, in that they were by and large aspirational: the library was an instrument of social or personal improvement.” (Pettegree, A., Weduwen, A. d., & Barrett, S, 2021). We must, then, move towards that what we find difficult and unsettling, in order to be relevant to readers and the library as we move into another year of library work. We need to be responsive organisms.

Window by Naomi Shihab Nye

Hope makes itself everyday

springs up from the tiniest places

No one gives it to us

we just notice it

quiet in the small moment

The 2-year-old

“kissing the window” he said

because someone he loved

was out there.

References

• Ranganathan, S. R., (1931) The Five Laws of Library Science [Madras], The Madras Library Association

• Pettegree, A., Weduwen, A. d., & Barrett, S. (2021). The library: a fragile history. [United States], Blackstone

• Hughes, L., 1902-1967. (1994). The collected poems of Langston Hughes. [New York], Random House

• Nye, N. S., (2020). Everything Comes Next. [New York], Greenwillow

The author is a library educator based in Goa, India. She can be reached at sujata@bookwormgoa.in.