Gopal Midha

A few days ago, I attended a “reflection meeting” at a school. The Head of the middle school was sitting with a few teachers. She began the discussion with some pointers about the approaching Annual Day. After 30 minutes of instructions on the responsibilities of each teacher, the discussion finally shifted into reflection mode through the analysis of a lesson plan. A teacher presented how she planned to teach the concept of “pressure” to grade 6 students. For the next 15 minutes, all the others in the staff room discussed how the plan could be improved and soon after, the school day ended for the weary teachers who were glad to head home.

I sat in the staff room as everyone left, thinking of what had happened. The school had allocated 60 minutes for reflection but what I observed did not really seem like a reflective session. Suggesting changes to a lesson plan would definitely involve thinking, but I wondered if all thinking was reflective? And what about the first 30 minutes of the meeting spent on administrative tasks? Why did “reflection” get sidelined? Was it just another case of urgent tasks usurping activities that are important? Do we come ready with the tools of reflection or can there be a method and structure to make it more effective for teachers?

I sat in the staff room as everyone left, thinking of what had happened. The school had allocated 60 minutes for reflection but what I observed did not really seem like a reflective session. Suggesting changes to a lesson plan would definitely involve thinking, but I wondered if all thinking was reflective? And what about the first 30 minutes of the meeting spent on administrative tasks? Why did “reflection” get sidelined? Was it just another case of urgent tasks usurping activities that are important? Do we come ready with the tools of reflection or can there be a method and structure to make it more effective for teachers?

So, I began to dig deeper into this concept of reflection and reflective engagement. This article presents my current understanding of this concept and presents a method which I believe will be useful for teachers and other professionals.

Reflection is important but how do we do it?

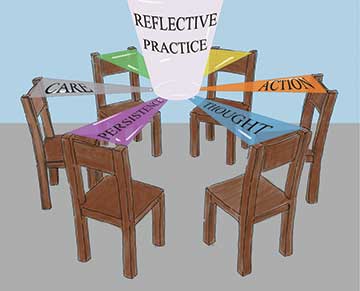

John Dewey describes reflective thought as an ‘active, persistent, and careful consideration of any belief or supposed form of knowledge in the light of the grounds that support it and the further conclusions to which it tends’ (Dewey 1933: 118). So, for thinking to be called reflective, it requires persistence, care, and action. Further, reflection tries to go behind the scenes and figure out what beliefs we hold and where they lead us.

This sounded like a good enough beginning. I am not sure that we are born experts on reflection. It seems like a deliberate and careful process of probing into the innermost chambers of thinking. And this might not be easy. First, a lot of our actions are grounded in beliefs hidden from us. Second, we never really were expected or supported to do this kind of thinking in school.

Most of our actions are based on assumptions we make about our environment and what we want that action to achieve. Let us take an example from an observer’s diary of a classroom. We pick the action mid-way while Arundhati (the teacher) is explaining something to her students.

…She writes the definition of a right-angled triangle on the blackboard.

As she writes, she says aloud, “A right angled triangle is one in which one of the angles is 90 degrees.”

I look around and see the students writing the same definition. I catch Arundhati looking back and doing a quick scan. Is all in order?

After she writes, she moves to the left side of the blackboard and draws a right angled triangle, naming the angles ABC. Angle B is 90 degrees.

She waits for a few seconds and then asks loudly, “Has everyone written this? Can I rub this?”

I hear a loud “Yes”. Some students are still writing though.

As she rubs the blackboard, she asks Jenil, one of the Grade A students in the class, “Tell me, what is a right-angled triangle?”

He stands up and then confidently reads out the definition.

“Good”, says Arundhati.

“Now who can tell me what a triangle is called if all its angles are below 90 degrees?”

A lot of hands go up.

An everyday experience like this could provide a rich source for reflection. It could help answer questions like:

- What are the assumptions that the teacher is making about:

• her classroom

• her students

• mathematics and

• her own teaching of mathematics - How aware is she of these assumptions that guide her actions in the classroom? Would she have a theory about how she acts – a theory of action?

Theories of action

In the 1970s, Chris Argyris and Donald Schon developed an interesting framework to describe why people act the way they do. They said that people always have a theory which guides their action. Suppose we asked the teacher the following questions:

Q: We saw that you wrote the definition of the right angled triangle on the blackboard. Can you tell us why? Also, what are the benefits of doing so?

Arundhati: Well… writing the definition helps students understand it. They have to copy it so they can re-read it. Then I can also ask questions which keeps them alert during the session and gives me feedback as to whether they are able to understand what I am teaching.

Her answer would be called her Espoused Theory*. A clear explanation of what her actions are intended to achieve and why. However, it is possible that on closer introspection and with support, she realizes that she writes on the blackboard and asks questions because:

- It keeps the students “busy”, maintains classroom discipline, and gives her silence to think through the lesson.

- It encourages students to compete with each other; it motivates them.

- That is the way she was taught and she now equates with her own learning.

All these are powerful tacit theories that she holds in her head and follows, and knowing them will help her become a much better teacher. Argyris and Schon would call them ‘Theories-in-Use’.

On closer observation, you might see that all these theories are designed to keep certain things (aka governing variables) within acceptable levels. These could be classroom discipline, respect for teacher, motivation, and so on. If I keep the students engaged in writing something, it will ensure that they are quiet! And once these governing variables are out in the open, it becomes possible to change them if required. And it is reflection which brings them out in the light.

So, at this stage, it might be useful to sit back and write a bit about your own classroom session. Here is a left-column and right-column method to do so. Give yourself a good 30 minutes of un-disturbed time. Start with an A4 size sheet.

So, at this stage, it might be useful to sit back and write a bit about your own classroom session. Here is a left-column and right-column method to do so. Give yourself a good 30 minutes of un-disturbed time. Start with an A4 size sheet.

Step 1: Draw a line in the centre of the paper dividing it into a right half and a left half. You can simply fold it once and then use the crease as the dividing line.

Step 2: Think of a critical incident in the classroom that you would like to reflect upon. A classroom situation which bothered you or made you happy or just left you feeling that something was amiss.

Step 3: In the right hand column, write a description of that incident as if a camera/objective observer was recording it. Be as factual as possible. Avoid judgments or interpretations. Be the camera eye and describe. Use lines/ bullet points for separate things you notice.

Step 4: Now, turn to the left hand column. For each point on the right, write as honestly as you can about what you thought and felt when it was happening. This is for your eyes, so you can afford to interpret. Be honest.

Step 5: As you write, you will notice the tacit assumptions that guide your work. Just make a note of it on a separate piece of paper. Probe softly about the variables which govern your work. Be honest and really gentle. I have a tendency to become a critic and judge myself for feeling angry or annoyed. That is not the idea here. Since reflection can provoke something unexpected about yourself, accepting it as it is will be useful. Imagine your closest friend supporting you through this process.

The exercise, when done repeatedly with different incidents, can be very powerful. Over a period, it will start highlighting some of the governing variables which you want to control. It will also allow you to discern various strategies that you use to keep them under acceptable limits. Sometimes, you will notice that your actions are not leading to the intended consequences (eg. Arundhati might note that students remember the definition but cannot apply it. Or only 4-5 students always answer her questions and the remaining students tend to switch off whenever she asks, “Who knows the answer?”).

Now, we are actually engaging reflectively on an action. Hard work, but the insights are usually worth it and save you hours of ineffective but hard work.

You might also notice that you can not only try different strategies to keep your governing variables in check (single loop) but also sometimes challenge your governing variables and change them (double loop). For instance, Arundhati might decide to try a different way to motivate her students without making them compete (say, increasing task diversity or giving feedback based on the richness of the response than on its speed). Or she could include a totally new variable – say mathematical thinking which she feels needs to be deliberately brought in even if the classroom could get a bit noisy.

To conclude, although our notion of reflection is usually sitting down and thinking, using a structure or a tool allows us to be more effective. And tools which require writing often help us slow down to see our own ladders of inference and the hidden assumptions that guide our actions.

The tool and the framework developed by Argyris and Schon can be used to identify our theories of action. It might not be a perfect all-in-one tool. It might require a group of teachers who could use it to share their insights. But the tool is simple and the only pre-requisite is complete honesty. The question is, are we willing to try it for a few times so that we know what works and how to use it well?

Perhaps, this might encourage a few of us to move away from feedback – oriented reflection meetings, where people just share what they feel like rather than hold their own ideas to a polite scrutiny. I hope it does.

__________________________________________________________________________________

*The word means ‘supported’ and interestingly, comes from the sense of take “as a spouse”.

The author heads the Policy and Program Evaluation Desk at Tata Institute of Social Sciences and works towards strengthening teacher education and support. He can be reached at gopalmidha@gmail.com.

Related articles

Can reflective practice be taught?

Observing really what is

Mirrors, images and reflections