Anjali Karpe

At a time when STEM courses are seen as clearly preferred…at a time when these courses get translated into “proper” jobs…at a time when technology is celebrated for its wondrous outcomes…it is indeed difficult to hold up the banner for teaching history. Economics, finance, and business still stand tall, but the same is rarely heard of history. But not absorbing history is like denying our self, our identity, our existence too in some way, because history is the window that allows us to understand the context behind every decision connected to those preferred subjects that have been placed on a pedestal. Ignorance of this and hence a denial of this will take us into a sterile world that is devoid of human emotion and relationships.

Dystopian as this may sound, it has to be recognized, and so the case for history must be made. After all, education strives to raise and nurture those who will take on the task to address the problems of the world, to right the wrongs, to extend fair play and justice to those who need it most, to empower the weak and infuse empathy in the strong. We will need politicians, scientists, economists, who approach their responsibility with care and a sense of equity. And these can never be imparted through a course on morals and values. And hence, the study of history.

It simply needs to work!

As a student in the 1970s and 80s I grew up traversing state educational boards to national ones as we changed schools with my father’s transferable job. While we grappled with challenges like studying Kannada that was a compulsory component of the Karnataka state curriculum and then suddenly shifted gears to deconstructing sanskrit grammar in Madhya Pradesh or then dramatically jumped levels of hindi literature in New Delhi, my memories of studying social studies transitioning into history are fairly consistent – there were textbooks that structured almost all events into a list of causes, events and effects; there was a minimal expectation of any elaboration of these points; and the grades would be earned on reproducing this content verbatim, with no effort at any variation in rephrasing or retelling.

Yet, I went on to study history and the one strong reason for this was the way history was viewed, discussed and deciphered on the home front. My father’s love for biographies recreated historical figures from Hermann Goerring to Mary Queen of Scots as we picked up the same books as part of gently-nudged, recommended reading; my mother’s love for monuments took us on wonderful road trips to Chittorgarh and Fatehpur Sikri and we were fortunate to get guides who were passionate and immensely knowledgeable. We were fortunate that the biographies were so well-written that we felt connected to the lives and times gone by; and our walks through these ruins helped us create wondrously, romantic visions of centuries past.

These experiences found their way into the history that was taught at my varied schools and while I studiously went through the causes and effects of events and memorized bullet points that wrapped up the story of an iconic individual, I was deeply conscious of another “side” to the study of this subject. Most of my classmates were less fortunate, and for them history was dull and boring, a meaningless recall of dead individuals and forgotten events, who had nothing whatsoever to do with their present.

As a teacher of history – teaching the ICSE as well as the IGCSE curriculum – I was determined to make this subject work for my students and ensure that they understand the relevance of history. Yes, it was a subject that studied the past, but they needed to see why this past mattered, how it had shaped their present – their being and thinking. Teaching the subject for the past many years, it is my firm conviction that if history is not approached as the means to make sense of the present and as a guide for the future, we will be doing a disservice to the subject as well as our students.

And I would like to begin by stating that the curriculum you have to teach may not lend itself to this approach. In which case, the challenge for the history teacher just gets harder. Having said that, the curriculum should never come in the way of the enduring understanding we want history students to have. It is with this goal that the history teacher must deliberately plan to stimulate student thinking, to ask the right questions and form balanced opinions; and to connect the dots and arrive at a better understanding of the world and its interconnected existence.

The question and extent of the WHY and the HOW

If you ask students why history should be studied, you might get glib answers that say – “because it repeats itself”, or “we should learn from the mistakes of the past….” These oft-repeated, proverbial statements have never been unpacked for students and very often they become meaningless as rote learning of dates and sequencing events take centre-stage for this subject. Beginning with the “why”, or the purpose of studying history, lays the foundation for all the questions that must be asked – not just why this subject is studied, but why certain decisions were taken at a certain point in time; why did things go right or wrong after such a decision; why did some things matter so much that they took a direction of their own; and why could some things not have been averted, leading to dramatically significant outcomes.

The why leads students to an understanding of causation – of a flow of events that had a seed sown at some point in time in the distant past. This in turn becomes the basis for a deeper reasoning and argumentation, the two key aspects of understanding significance and the impact of individuals and events in the short term as well as the long term. It is this significance that imbues meaning to the study of past events as students try and gauge that the long-term impact very often leads into their present world; in fact it answers so many questions about why we think or believe or act the way we do. Think of cheering loudest for India in a quarter final India-Pakistan match versus the milder excitement when India plays West Indies for example, in the finals!

As we start arriving at conclusions though, students tend to wonder and question the extent to which happenings of the past are significant. Being able to weigh significance or impact and then synthesizing this into a greater understanding of historical development from the past to the present is perhaps the most important aspect of critically thinking about our time and place in the present. The teacher of history helps students to construct these elements – not by feeding them with chunks of content, but by providing them the skills to decipher and interpret a whole range of historical sources.

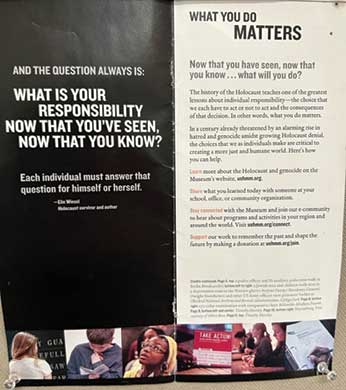

Becoming historians can be empowering for students. With the bare outlines of a story given to them to set the context, try giving students sources – extracts from diaries, newspapers, letters, speeches as well as photographs and cartoons. The effect is almost magical for them as they start spewing out greater details, building and supporting the skeletal story you have started them with. As a teacher, your job is to extend that first shot of curiosity that is sparked when students start constructing details of their own accord, with their own understanding and knowledge. The deep satisfaction to see your students transform from passive listeners to active historians has an excitement that is hard to describe. Very often a brand new unit can take off starting with just looking at sources, scanning them for literal details and then moving on to wider interpretations and deeper connotations.

The internet is the best thing that happened!

At a time when the internet throws up every possible detail of information, what can a history teacher possibly unravel to students? The answer to that is NOTHING! There is nothing that you can give to your students by way of details that the internet does not do better! But this dramatic announcement rides on the back of a transformation that is imperative for history teachers. Reinvention is crucial and if we do not want to be replaced by a device, we will need to redefine our role. In some ways we are liberated from being wise sages who are meant to know every detail about everything. What can we now do with this pile of detail is the question and we can immediately move towards getting our students to think – a higher level skill that will completely replace the traditional rote learning that has been associated with the subject.

Students will gradually conclude that just because there is all this information available at a click, it is neither accurate, nor trustworthy, nor relevant to a specific study. Being able to cull out content is a skill that must be guided, and this will be connected to the scope of the question being asked. This deep understanding of the demands of the questions cuts across subjects and disciplines.

With the content so accessible, the nature of questions being asked and considered will need to change as well and thus one can move higher in the pyramid of Bloom’s taxonomy. Recalling information should frankly be brought down to a minimum. Where in the future will our students have to rattle off a ton of recalled data? In fact, they will need to get used to confronting data and then making sense of it. As teachers we can prepare them by giving the information and then posing questions where they have to analyze and apply. And yes, it means upskilling for teachers who will no longer be needed for their knowledge base alone, but more to direct students to think, research, and create.

The excitement always spills over!

Teach history because you are passionate. Of course this applies to every subject that is part of a curriculum. But I place it here because it has to be consciously considered when embarking on teaching a history program. For a subject that spans our political, economic, social and cultural journeys over time, a subject that defines our identity and endeavours, it is impossible to get students to realize and reflect at this enormity without the teacher’s passion and excitement.

Mapping activities and assessments by reliving, recreating, and retelling the past is one of the most effective ways of channelizing this passion to engage students. They will need to step into the past through the projects they undertake and travel independent as well as group journeys. Taking on the persona of an individual from the past and writing a letter or diary will give them a perspective that is far deeper than going through a list of landmark events associated with that individual. A range of these created letters and diaries will allow a group to share, argue, and discuss individuals and issues, perspectives and dimensions.

Get students to create their own newspaper, time-stamped as per your unit of study and give them a clear structure of what their articles should cover. Here again, the nature of questions will guide your students through delving into the stacks of information to pick out relevant details, use the content to make connections that expand to cover a deeper understanding and arrive at conclusions that broaden their horizon of human civilization. All these will mould thinking in ways that no lectures on values and ethics can manage and the lessons will have deep roots because they are learnt through journeys of self-reflection.

The purpose of studying history is vast as it weaves innocuously through a range of stories of human beings and the civilizations and cultures and empires that have brought us into being. As teachers let us give our students a fair chance to deep dive into this study. Otherwise, we will most certainly fall into the trap of proving that the only reason to study history is to glibly conclude that it repeats itself.

The author is the Deputy Head at the Bombay International School in Mumbai. Besides being a passionate teacher of English Literature and History, she is a strong believer in holistic education and has worked consistently in areas that foster learning outside the purely academic domain. Student leadership, co-curricular pursuits and strengthening student agency through empowering them has been key to her journey in education. She can be reached at anjalikarpe@gmail.com.