Lakshmi Mitter

The question “What do you understand about human-animal conflict?” elicited varied responses from the 8–11-year-olds, such as:

“I know what ‘conflict’ means, but I don’t know what ‘human animal-conflict could mean.”

“Maybe it means humans fighting with animals,” said another.

“Fighting with animals as in fighting for something? Humans may need animals for something and to capture them they need to fight.”

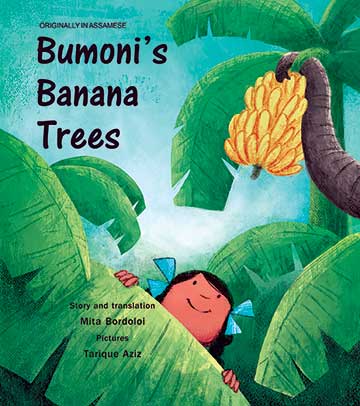

As I listened to this conversation, it occurred to me that those of us who live in urban areas seldom encounter wildlife and are therefore unfamiliar and not very sensitive towards other creatures. Our association with wildlife is limited to books or the television; at the most some of us might have gone on a wildlife safari. We may or may not be able to do much in terms of conserving wildlife, but knowing why it is important is something we must be aware of. Just as these thoughts started taking root in my mind, I read an interesting article titled, In harmony with nature in Teacher Plus (February 2023). The article introduced me to a wonderful book, Bumoni’s Banana Trees written by Mita Bordolai and illustrated by Tariq Aziz. In the book, the protagonist, Bumoni sees elephants from the Kaziranga National Park visit their backyard to eat bananas. This goes on for consecutive nights. The family is forced to think of way to stop the damage, but Bumoni also wants to help the elephants!

My mother, who also read the article, gifted this book to an eight-year-old and was keen to have a fruitful discussion with the child’s mother about their reading experience. Much to her annoyance, the child’s mother said her child had read the book and would like to return it so that it could be passed on. More than the shock of seeing her well-intended gift being returned without any appreciation, the fact that this mother and child could not enjoy some time together reading and talking about the book appalled her.

What would it be like to read Bumoni’s Banana Trees together?

My mother and I talked about the book at length and the lukewarm reaction from the child’s mother. It occurred to both of us that probably the child had been given the book and asked to read by himself. It’s likely that once he finished, he gave it back to his mother and it ended there.

We went back to the article, In harmony with nature, and discovered that it suggested that the book be read and enjoyed in a group. I decided to give it a try and introduced the book to my young reading companions (8-11 years of age).

We first spoke about human-animal conflict and then opened the book. The very enthusiastic group of readers were drawn in right away on seeing Bumoni walk out of her backyard plantation, looking happy, holding lots of bananas, and her dog following her with a banana. We talked about what it would be like to have a big banana plantation in our backyards. Interestingly, the concept of a backyard itself was new for many children suggesting that the only kind of homes they have known are apartments. But that did not stop them from coming up with business propositions to sell the extra bananas after Bumoni’s family had had their share. The young always teach us to think forward.

As we read along, we looked up images of banana blossoms. Some had tasted it and said they hated it. My telling them of its health benefits fell on deaf ears. Others who had neither seen nor eaten it were fascinated with its many layers and the time and effort it takes for preparation before it can be consumed. Each child, however, had eaten on a plantain leaf.

When we got to the crux of the story where Bumoni’s family has a problem to solve, the group had interesting reactions. Here are a few:

- Let’s block the river to prevent animals from the forest from crossing, but that’s cruel.

- What if we build a fence around the plantation?

- What if we call the forest department for help? Perhaps they don’t know.

- What if we call animal caretakers for help?

- What if we make provisions to feed the animals who crossover from the forest to the fields?

- Can the zookeepers help? This question led to an older child in the group explaining the difference between a National Park and a zoo. Furthermore, the group realized that National Parks are wilderness areas (usually large) that are home to many species while zoos have select species in captivity.

- Why do we need wildlife when all they seem to do is to cause trouble? Why conserving wildlife is crucial for human existence? The children began to appreciate that it is not only a question of empathy towards animals but also a matter of ecological balance – not just about one of us but about all of us. That discovery at some level became possible, thanks to this book.

Talking about how this book came into being

The author Mita Bordolai wrote this book with a purpose. But how did she get the idea? We read the interview that was part of the Teacher Plus article. Most came to know about the Kaziranga National Park for the first time while a couple knew about it from their textbooks and maps. However, beyond that they knew very little about it. The interview in the article gave the children an inside look into how this fascinating book came into being. At the end, a young reader observed that while coming in close proximity of wild elephants would have been a scary experience for those who were at close quarters, for the readers it was definitely a major learning.

The author is the founder of Talking Circles – an online cohort-based learning program. She can be reached at lakshmi@talkingcircles.in.