Rupangi Sharma

Every educator is a design thinker. You solve the problem of quality learning and education which is your product and service. You make millions of decisions to address the problem statement: how can I make learning more enjoyable and effective? Your customer or user is your student. You understand their needs, empathize with the problem areas where they are struggling and then realign your goals in a way that will meet their learning needs. That is what human-centred design is all about.

Based on what your students need to focus on, you then develop lesson plans and modules for your classes and when you teach them you make a mental note of what worked and what didn’t. Your lesson plans and modules are prototypes that you test when you walk into your classroom. When you realize – sometimes instinctively and other times through students’ explicit feedback – that something isn’t working, you go back to the drawing board and then reiterate on your lesson outline. This process repeats itself as a continuum till you have a product that solves your customer’s needs.

In other words, design thinking is a cyclical process that starts with empathy. Empathy is the ability to understand and share someone else’s feelings. As an educator, when you understand what your students need, you empathize with them. And once you step into their shoes, you can define what needs to change, ideate on how you can make that change, create a prototype and test it in the classroom. That’s what the design thinking cycle is – an incredibly empowering tool to create impact in any and every field. As a design thinker, you are armed with the right skills and techniques to solve problems. You start to see problems as opportunities for designing solutions.

In a world that is rapidly changing and evolving, that’s just the kind of mindset all of us have to develop, especially our students, who are faced with a future that will continue to be riddled with climate change, technological advancements rapidly replacing jobs, and many such complex factors that require the ability to solve difficult problems. They face an unpredictable future, one in which they will need to think creatively, befriend failure and problem-solve to create a better future for themselves.

I joined the field of education after reading Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed, and realizing how much I agree with Freire: students are not containers that teachers fill with their knowledge. The ‘sage on the stage’ method of teaching is outdated. As someone who is a creative thinker, I always felt betrayed by some parts of the education processes I was exposed to as a student. Why couldn’t students be co-creators in their learning journey?

Students should take a more active role in designing their own learning experiences and reflecting on them. Not just that, there is nothing more powerful than peer learning: if that’s something that we leverage at a Master’s level, why not start from pre-school? Research shows us that you learn when you teach. Add to that, humans are social learners. So, peer learning and peer teaching translate into extraordinary results in the classroom. In my first year of teaching, I saw the impact of small changes like asking my students to stop addressing me when they speak in class, and instead make eye contact with their peers and learning to truly listen to each other. Later on, I utilized processes and technologies that would build a collaborative classroom environment in which students teach and learn from each other.

I also strongly believe that our system of segregating subjects and creating silos in the process of inquiry inhibits a student’s naturally playful curiosity. Inquiry necessitates asking questions and encouraging students to question every assumption, belief, and knowledge recorded so far in textbooks. The most impactful innovations, historically, have challenged pre-existing assumptions and experiences, and they have taken root in interdisciplinary forms and evolved over a period of time. Case in point, the computer and internet were military innovations. An innovation in a particular field has spillover effects and it’s when like-minded people with the same passion share knowledge and collaborate that industries are spawned.

When I taught innovation and design thinking to students, as an experiment to test their assumptions, I asked them: who is an innovator? Hands shot up as I scribbled their replies on the board: Steve Jobs, Einstein. But they sensed I wasn’t satisfied with their answers. I paused and then asked them if they thought they could be innovators? Some of them looked at each other and shrugged their shoulders, puzzled by my question.

Another student said, “But, everything in the world has already been solved!” That’s exactly the kind of fallacy that our textbooks teach our students, since they fail to talk about the complexities they will face in the real world. We, as educators are complicit too, as we fail to tell our unsuspecting students that when they walk out of schools, all they will ever be faced with are problems that have not been solved! This is also precisely why we must teach our students design thinking, which apart from its applications in creative careers, is a mindset and framework that cuts across fields.

Design Thinking has powerful contemporary life skills, like creativity and collaboration, embedded in it. Now let’s get down to brass tacks. How can educators impart these skills in the classroom? I have taught scores of students to be design thinkers and innovators as well as teachers to a) role model and teach design thinking (DT) b) design their curriculum using the DT framework. I have also trained CXO (C-suite) level management on design thinking and its application. Let’s break down the DT framework:

- and 2. The first two steps are interlinked, as you begin by empathizing with your user and defining the problem you want to solve for them: The first step in the DT process is to define a problem that you would like to solve. How do you go about doing this? The easiest way to do this is to reflect and think about what kind of problems you see in the communities and groups around you. In my book, Young Innovators, Entrepreneurs and Change-makers, I have profiled the stories of 65 young people between the ages of 7 and 21, who have solved a range of incredibly complex problems, and now run their own social enterprises and businesses to scale their impact.

Their personal experiences or conversations with groups of people around them contributed to their aha moment. For Harshita Arora from Saharanpur, who sold her cryptocurrency app to Redwood City Ventures in Silicon Valley in her teens, and whose payments infrastructure start-up has now received a $75 million funding – the idea for the former was sparked when she spoke with like-minded friends on online platforms who advised her that there is a massive need for a cryptocurrency app for investors.

So, start by talking to people around you, doing in-depth research online and through surveys, and reflecting on your own experiences to empathize with the end user. More likely than not, if there is something that bothers you (you can also be the user), it is a local problem that might have global applications. Ask your students: what is something you want to change?

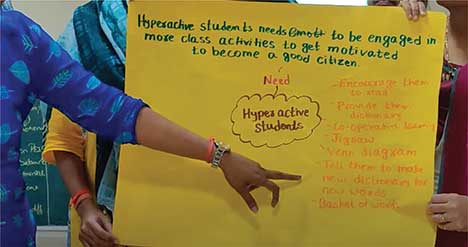

- Ideate on the solution for the problem: Now that you have defined the problem, you need to come up with a list of ideas to solve it. At this stage, you don’t want to limit yourself to a particular idea or scope, so you can scribble down any and every idea that you have to solve this problem on a chart paper. Don’t think about whether you have the skill sets to design that idea, just concentrate on coming up with a long list of ideas that can effectively address the problem you want to solve.

- Create a prototype: After you’ve drawn up a long, out-of-the-box list of solutions, as a group start discussing and zeroing down on the one solution you would like to build on. For this solution, you can create a working prototype which is as simple as a role play, a PowerPoint presentation, a situation-based story, or wireframes. Remember, the idea behind prototyping is to rapidly communicate and test it with the group of customers or users for whom you intend to solve the problem.

So, let’s say you decided that as a group of educators you want to teach Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in the classroom and feel that is the gap that you’d like to solve, you can come up with a lesson plan and role play it with each other for feedback before the final step of testing it out with students.

- Test your prototype: Go to your user and show them the prototype. Your goal at this stage is to ask for feedback. Does the product you have created address their needs? Was there something that you have missed out on? Incorporate the feedback into your product design.

In a nutshell, you and your students have just experienced the human-centric design thinking process that has unlocked miracles and empowered millions of people to design celebrated products, services, and experiences!

The author is the founder & CEO of EFG Learning: Education for Growth, a Mumbai-based education consultancy. She has worked with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Media Lab, Boston and other leading institutions in India and abroad. She was invited to be a panelist on the advisory board to design the ICT in Education Curricula for the Central Institute of Educational Technology (CIET, NCERT). She has recently written Young Indian Innovators, Entrepreneurs and Change-makers (Puffin, 2022). She can be reached at rupangi@efglearning.com.