Samina Mishra

The other day a friend shared how after reading the newspaper every morning he felt a heavy sense of dread and asked how I was coping given the darkness of the times. His question made me think of my everyday that takes me into the lives of different groups of children. In the last eight months, I have spent time in three different parts of India, talking to children about their ideas of citizenship. Many of these children live with want – their homes are in neighbourhoods with poor infrastructure, their schools have limited resources, they have to carve out spaces for play in congested areas, and so much of what they see on phones or TVs are beyond their reach. Their worlds are so very different from mine, insulated as I am by privilege from the everyday harshness of the despotic world we live in.

What then does it mean for someone like me to ask them about Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity in this 75th year of India’s independence? Lata Mani speaks of how “the stories we tell locate us”. It is my hope that through Hum Hindustani, a project on children and citizenship, I am able to tell stories that both recognize and rise above differences so that we can also remember the commonalities – that at independence, we were all promised Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity, that it is our right to ask for these, and our responsibility to realize a world that honours these.

Much of my engagement with children revolves around creative practice, through a sharing of artistic work as well as a process of co-creation. The arts in the classroom – formal or informal – encourage children to look at their world and to look at it aslant, in ways that they may not have looked before. The arts also enable self-expression, encouraging children to express their thoughts and in that process make sense of their lives and worlds. The scholars, Michael Bonnett and Stefaan Cuypers (as quoted in Beauvais) explain, “It is only by expressing them and feeling the world’s response, either actually or through acts of the imagination, that we discover what our thoughts really mean and what the world means to us”. Children’s engagement with the arts enables this discovery, allowing them a space to be and become simultaneously, to articulate and form at the same time. Just as I clarify my articulations even as I write this essay, forming a sense of responsibility for my thoughts, creative engagement can give children a chance to build a relationship with the world that includes a sense of responsibility for it. This has been made clear to me, again and again, in my interactions with children.

This essay is based on a project that draws upon my previous work with children in collaborative creative practice using text, image, and sound. The project, Hum Hindustani, includes creative workshops with children that are designed around the ideas of Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity, using group discussions as a lead-in to work being created by the children on a variety of prompts. In this essay I will focus on one such interaction that led to the writing of a poem on the prompt, Mere Log (My People) by two teenage girls in Govandi, Mumbai.

Natwar Parekh Compound, Govandi

Natwar Parekh Compound (NPC) is a collection of high-rise buildings in Govandi, built in 2007 as part of the Slum Rehabilitation Authority’s provision of formal housing to slum and pavement dwellers from different parts of Mumbai. People from more than 10 different locations have been relocated here, making way for various urban infrastructure projects across the city. With more than 25,000 inhabitants, the 5-hectare neighbourhood is one of the most densely-packed urban areas in South Asia, and the relative space available per person is as low as 1.9 m (Community Design Agency). Many of the inhabitants of NPC are permanent residents but there are also several who are tenants. The attached bathroom, piped water connection, and elevators in each building were attractive for most of those who moved here, but the reality is that infrastructure remains a big challenge. The alleyways between the buildings are piled up with years-old garbage, broken drainpipes discharge sewage onto the streets, and damaged streetlights are common. Much of this is being addressed as part of a revitalization project by Community Design Agency, an organization that has been working in the area since 2016. One of the steps taken in collaboration with the residents to find solutions for the challenges faced by the neighbourhood has been the setting up of a library for children, Kitaab Mahal. The library is envisaged as a catalyst for building community engagement and creating a space for children to learn, particularly during the pandemic when online learning in their cramped homes was difficult.

Kitaab Mahal was the site of the art and writing workshop that I conducted with 13 children – 8 Dalits and 5 Muslims (Ansaris, a caste that is considered OBC) – from classes 6 to 9, enrolled in both municipal and private schools. Two of the children were out of school – their family had moved to NPC during the pandemic and the parents had not yet received the transfer certificate from the earlier municipal school. As daily wage-earning rag-pickers, it was difficult for them to make time to follow up on this, so the boys remained out of school at the time of the workshop. S and K, the two girls whose poems are the focus of this essay, are both 14-years old and had just finished grade 8 in municipal schools at the time of the workshop. Both liked their school though they expressed that the two years of online schooling during the pandemic had been difficult and that there had been little learning. This was evident in their writing skills – they asked for help in writing even simple words. S belongs to a dalit family from Maharashtra and lived in Powai before moving to NPC. K’s family is from Uttar Pradesh, also dalit, and she spent several months of the pandemic in her village before returning to Mumbai when her father could go back to work. Both families have been living in NPC for several years.

The girls were both quiet and shy, needing a lot of encouragement to speak. Both are regular visitors to the library, with S also volunteering and reading stories to younger children. In one-on-one conversations, both expressed an awareness of their caste identity – they spoke of being “low caste” or “chhoti jati”. K spoke of being Hindu and that there were castes among Hindus. “We are Jaiswal…” she said, “I don’t know exactly but maybe… they say chamaar, no? Like that… so, they call that a chhoti jati, low caste”. The way they spoke about caste revealed the intersecting experiences of religion, caste, and class. “Caste means different religions, different communities,” said S, “Caste means different religions, like Jai Bheem, Marathan, Christian. There’s a lot of difference between Jai Bheem and Marathan. Meaning Jai Bheem is another caste, Marathan another. Those people don’t accept everyone, don’t accept the Jai Bheem people”. K also spoke of families that speak nicely to her and families that don’t, but in her articulation, the lines were drawn somewhat differently – “Because those people are also Hindu and think they are like us”.

Both know about Ambedkar, as the author of the Constitution that had abolished caste differences and as an almost-God for their community, whose birth anniversary is celebrated with ritualistic worship. For April 14, Ambedkar Jayanti, NPC is abuzz with activity – string lights and posters are put up and temporary statues (idols) of the Buddha, Ambedkar, and Phule are installed and garlanded. People visit the various sites nearby, including mobile trucks decorated with lights, coloured blue to signify dalit resistance. The trucks play popular Marathi songs about Ambedkar and dalit unity on loudspeakers and people dance together. In neighbouring Chembur, there are long queues of people waiting to pay their respects to the statue of Ambedkar that stands in Ambedkar Garden. Families from NPC go there and to Shivaji Park where a huge celebration is organized. S said that she, like most people, dresses in blue and white colours on April 14 and the family makes kheer to mark the special occasion. K took me to the local Ambedkar statue in the square between buildings at NPC and prayed there as if it was a shrine. “Today is his birthday and he wrote the Constitution for our Bharat. And in the Indian Constitution, religion, our Hindu religion here that has caste, that everyone considers untouchable… that’s why Babasaheb Ambedkar wrote the Constitution.”

Their knowledge of the Constitution, however, and the rights it bestows was hazy. For example, S shared, “I don’t have any rights in the country…” There was a very clear articulation of class inequality, both in relation to the larger city of Bombay where class differences are starkly visibilized in the 5-star hotels that are inaccessible to them, as well as within NPC with some families having more than others. K spoke of how people with more money in NPC had fixed up their homes with tiles and now did not want to mix with families like K’s who had not been able to do the same. She also spoke of many Muslim families who were reluctant to let their children talk to her. In contrast, S expressed a great closeness to Muslims – “I like the Mohammedan caste… because I have said namaz with them… I like that caste. Because I have lived with them, na.” Her close interaction with Muslims including her best friend, she said, gives her insights into how they feel when there are calls to ban the azaan or to not allow girls into school if they wear a hijab. “That is not right,” she said.

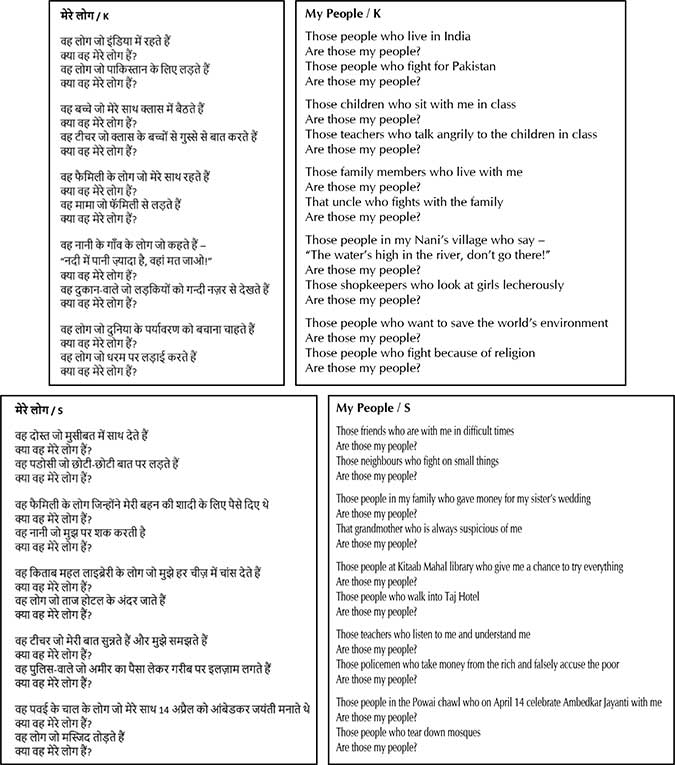

The poems

It is in this context that the poems written by K and S emerge, as a response to the idea of fraternity that we discussed as apnapan, a feeling of being one with others, of being oneself and together, comfortable and with a sense of belonging.

The poems present a tapestry of everyday vignettes from S and K’s private and public lives that ask us to reflect on conventionally accepted notions of community and belonging. What can this experience of writing mean for the children? What is the adult’s role in the process? And what can we learn from listening to them? These questions are explored in the next part of the essay.

(To Be Concluded)

The author is a documentary filmmaker, writer, and teacher based in New Delhi, with a special interest in media for and about children. Her work uses the lens of childhood, identity and education to reflect the experiences of growing up in India. This article is based on her research project, Hum Hindustani for TESF India.