Samina Mishra

When children write from their lives, they are both expressing what they feel and developing a sense of self and of the world. They think of what has been important to them and in making that choice they begin a process of understanding why it is important to them. This continuing part of the essay (the first part appeared in the January 2023 issue of Teacher Plus) explains how a writing exercise on a prompt relating to the idea of fraternity worked as a process of co-creation, allowing for a richer understanding for both children and adults.

The prompt and the process

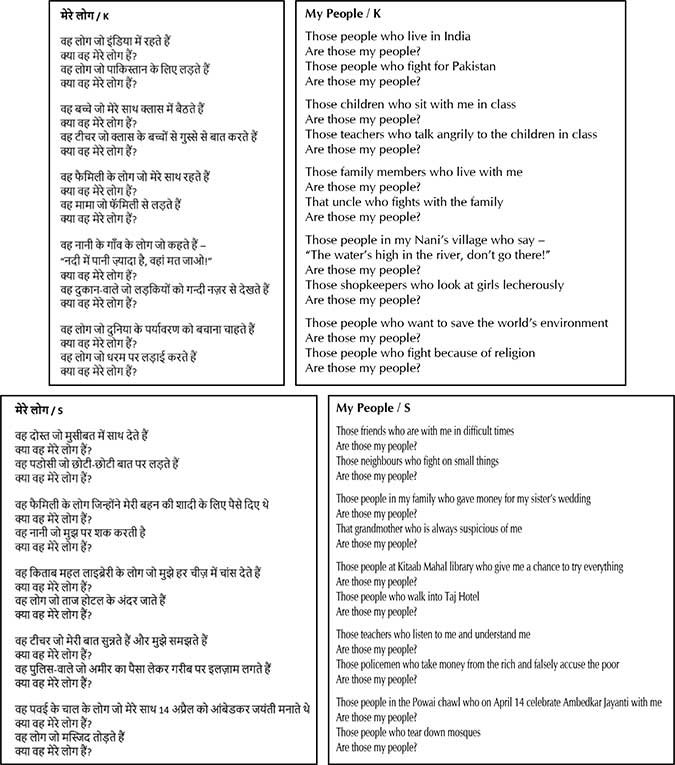

The word fraternity translates in Hindi as bandhuta. However, this is not a word commonly used, and so for our discussions, I chose to use the word apnapan, which evokes a sense of belonging in reference to people one considers one’s own. Thus, the prompt I gave them to write was Mere Log, My People. As the facilitator, my central concern was to enable them to express in their voice. So, it was necessary for me to emphasize that they draw examples from their lives, their worlds. There are myriad ways in which people make ideas their own by living the intertwined lives that they do. Children receive ideas like community, caste, rights, and citizenship in different ways, but they really make sense of them through the everyday that they experience. The everyday is not neat and orderly, it does not fit into existing frames, it can even seem to create confusion. Children walk and play in that everyday, sharing space in a site where both public and private spaces are limited. It is from those lived experiences that they find ways of being together, of seeing each other as both different and same. Thus, it is to the everyday that I turned to enable the children to express in their own voice.

In our individual conversations, K and S had spoken of people they felt were their own and as shared earlier, the responses did not reveal neat boxes of belonging, formed out of religious, caste, or class groupings. Instead, the everyday experiences reflected overlapping spaces and groups where they felt a sense of apnapan. But for the purpose of the exercise, I needed to create a structure that they could use and flesh out with their own examples. I did this by first identifying the spaces in their lives that we could explore – the home, school, neighbourhood, and country. I then asked them to make a list of situations where they felt they belonged, when they had felt a sense of apnapan, as well as a list of when they had not, for each space. This helped to connect the abstract idea of fraternity and belonging to tangible material spaces and lived experiences. I then suggested that select examples from the list be written up along with the use of a repeated line to create a rhythm for the poem. At first, I suggested drawing from the prompt, Mere Log, to create a repeated line like Woh mere log hain (They are my people). But this would not work for the situations lacking apnapan. So, as we talked about how to turn the lists into a poem, I suggested that throwing it open as a question may be a better approach. This led to the use of the repeated line – Kya woh mere log hain (Are those my people)? Thus, each space was explored through a juxtaposition of situations chosen by them, where they experienced apnapan and where they did not, followed by the interrogative repeated line. The use of first person, of specific names such as Kitaab Mahal or nani ka gaon, of direct speech in some places were all suggestions that I made as stylistic devices that could be explored. Once the four stanzas were done, there were some other examples left and we talked of an introductory stanza that could be in any space. Thus, the opening stanza for both evoke the idea of fraternity, in K’s poem through the idea of nations and in S’s through the idea of friends and neighbours.

My asking them to create two lists – when they had felt a sense of belonging and when they had not – did create a binary of their experiences and it is likely that the reality is a more overlapping one (just like their sense of identity overlaps across class, caste, religion, gender, etc.) with the feeling of belonging, apnapan, being a spectrum. However, this was a constraint of the exercise and of the kind of time in which it had to be completed. It is also reflective of my role in the process that created a structure to examine the idea of fraternity in their everyday. This needs to be remembered (and an exercise can be followed up with more detailed work or interviews to explore the spectrum), but I do not think it takes away from the children’s assessment of the particular experiences that they included or from the meaningfulness of their writing. While the juxtaposition of situations is indeed present in each stanza, the use of the interrogative repeated line throws both situations up for questioning – questions to be considered both by the writer and the reader.

The finished poems offer a layered understanding of the different structural categories that intersect in the lives of these two teenagers. The examples that both use as a response to the prompt reflect the tapestry of everyday working-class lives – the tension within families that destabilizes the idea of family as belonging, the shopkeeper who may belong to the same neighbourhood but whose gaze makes him a predator, the power inequalities that make the poor vulnerable to police action rather than feeling protected by the police as citizens, the different kinds of teachers and classroom experiences that can forge a sense of belonging and un-belonging, the coming together of different people to celebrate a dalit festival and the dalit thinking of the masjid-goer who will lose the masjid when it is torn down. We cannot say for certain whether the articulation of these tensions changes the way these children will engage with the world and with others, but the articulation contains within it the possibility. As the child-writer asks the question in reference to different situations and people, she may or may not have arrived at an answer but she is considering the question of who her people are. This is “the mighty child” that Clementine Beauvais talks of, holding within the uncertain future, “more time left” in contrast to the adult’s “more time past” in which all possibility is frozen (Beauvais).

Drawing from Beauvais’ contention that the children’s book may become the source that teaches the mighty child something that the adult does not know yet, it is my belief that the child’s creative articulation may fulfill that same role of the children’s book. For instance, in juxtaposing all those who live in India with all those who fight for Pakistan, K throws up the question of a forced belonging, of who gets to choose where to live and who to fight for. That is a question not just for us as readers but also for her as she orders her thoughts – are all the people of India really her people, even those who call her “chhoti jati” and stop their children from speaking to her? And so, could it be that she may actually feel a sense of apnapan with some who fight for Pakistan, even though they are across the border in a country that is a sworn enemy of India’s? What if they are, for example, part of those who want to save the world’s environment as she says in the last stanza? Similarly, S complicates the idea of apnapan emerging from caste or religious groupings when she asks the question in her last stanza – are all those who celebrate Ambedkar Jayanti my people, are all those who destroy mosques my people? S is attuned to incidents about contested mosques in other parts of India, even though she is not Muslim and these mosques are not in her vicinity, because she feels a closeness to the Muslim family she has grown up with and this is an issue of concern for them. This is the mighty child’s simple articulation that may teach both her and the adults what fraternity can mean.

This exercise is an example of a process of co-creation in which the framing is clearly adult-led. I chose the prompt, I chose the spaces to explore the manifestations of apnapan, I made suggestions on formal choices such as the use of direct speech or names. I definitely wielded authority. And yet, there was an element of uncertainty. I could ask the questions, make the suggestions but I could not control what they would respond with, what examples their lived experiences would throw up. Thus, the moment of writing each line was actually a moment where our differences and commonalities intersected. I brought my lived experiences through my thoughts to that moment and they linked that to their lived experiences to create the final line. It is a moment fraught with the possibility of several options, with the final choice being made by the agency of the child. And once that choice is made, the child reveals to both herself and to the adult the possibility that lies in the future – a way of reimagining apnapan, of redefining “my people”.

Conclusion

Spyros Spyrou has written about research with children and made a case for the researcher’s self-reflexivity so that we may acknowledge “the messiness, ambiguity, polyvocality, non-factuality, and multi-layered nature of meaning in ‘stories’ that research produces”. This essay presents an example of that ambiguous, poly-vocal process with multi-layered meanings. The question – Kya woh mere log hain – emerging from an adult voice intersects with the multiple examples in the children’s voices that infuse the question with a poignant simplicity. There may not be certitude at the end of the poems, neither for the reader nor for the child-author, but they certainly contain the possibility of multiple meanings. And so, by listening to what children say, might we find more meaningful and less restrictive ways of understanding ideas like community, public space, rights? When children express their thoughts in this form, will we listen and look at the world in a new way?

So, to go back to my friend’s question (from the first part of this essay) – how do I cope with the darkness of the times? I think that while it is certainly swirling around us constantly, the darkness dissipates for me in little everyday chinks because I am privileged to work so much with children. It is not just about the lightness that interactions with children bring but also about the hope that they offer. Children carry the burden of futurity that may seem unfair as if the responsibility of fixing a broken world is simply transferred to them by a generation of abdicating adults. But this is in some ways inescapable – the future is a priori theirs and adults can only be allies in that. In that process, it should be incumbent on adults to excavate and glean the possibilities that exist in human interactions before they get tainted by prejudice, before we forget the simple ways of connecting over differences. Children’s writer, Katherine Rundell writes, “So many children’s writers and illustrators are themselves already hunters and gatherers of hope; manufacturers and peddlers of wonder.” To work with children, to create art for and with them, is a process of discovering the world anew and remembering that there is always another way of being. To work with children gives us the privilege of holding on to light.

References

• Beauvais, Clementine, The Mighty Child: time and Power in Children’s Literature, John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2015

• Community Design Agency

https://communitydesignagency.com/projects/natwar-parekh-colony/

• Mani, Lata, The Integral Nature of Things: Lata Mani in conversation with Amlanjyoti Goswami, Public Texts a@IIHS, 5 February 2014

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wKuj2mFx7XQ

• Rundell, Katherine (Ed.), The Book of Hopes: Words and Pictures to Comfort, inspire and Entertain, Bloomsbury Children’s Books, 2020

• Spyrou, Spyros, The limits of children’s voices: From authenticity to critical, reflexive representation, Childhood, 11 April 2011

http://chd.sagepub.com/content/18/2/151

The author is a documentary filmmaker, writer, and teacher based in New Delhi, with a special interest in media for and about children. Her work uses the lens of childhood, identity, and education to reflect the experiences of growing up in India. This article is based on her research project, Hum Hindustani for TESF India.