Thomas Kenning

Are you teaching with the spirit of a traveller?

Have you ever felt as if, whether you liked it or not, your classroom was a box, hemming in the potential of your teaching, your students, and your ambitions?

Sometimes the day-to-day limitations of our routine can narrow our field of view – it can seem like the only part of the world that matters are within those four prefabricated walls.

Education should be about opening borders and horizons, both literal and figurative – we should be fostering in our young people a sense of wonder about the world and our place in it! A sense of connection to their fellow human! And yet….

Take attendance, take notes, take a test – as if you and your students were walking a treadmill….

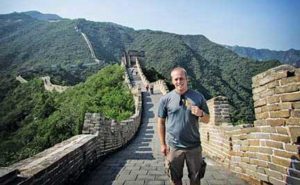

I am a middle school social studies teacher and I wrestle with this tension every week as I attempt to transport my students to some far off time or faraway place. If my class were a movie, you’d be riveted – it would be the blockbuster that pleased every audience and broke all records, with a cast of billions and a budget to build the best setpieces ever dreamed of – the Great Wall, the Taj Mahal, Machu Picchu, the Saturn V rocket, all to scale. If you think history is boring, you had a teacher who was doing it wrong – so very wrong.

But maybe it’s not totally that teacher’s fault.

I feel like it wasn’t mine – I was armed with low quality, uninspired curriculum, approved by some committee I’d never met, locked down under copyright and digital rights protection so it couldn’t be accessed on my students’ smartphones – often their only means of connecting to the Internet outside of school – and designed to be inoffensive to the most sensitive parent who might see it. In effect, it was bland and devoid of inspiration, meant to be quantified and standardized so that it could be tested like the skills learned by rote in a math class.

I realized how bad all of this was when, in my 20s, I started to travel.

Because travel is anything but bland or uninspired.

Scrambling through the sprawl of Angkor Wat, ancient splendor now laid waste, home to a sense of awe that cannot be dampened under any amount of ruin –

Riding the crowded streets of Manila in the back of a Jeepney, sweat on my brow, and taking the generous advice of fellow passengers, strangers as they may be, to ensure that I don’t miss my stop –

Hiking an ancient Inca road, gasping at the thin Andean air, worried about making it over the high mountain pass before the snow begins to fall, only to be lapped by children in sandals who make this trip every day to reach their school in the village below, singing as they go –

How could anyone come away from these experiences uninspired? And yet, my students’ dry, antiseptic textbooks hinted at none of these real world lessons…

Take what I learned while hiking my way through Peru: The Inca were one of the greatest civilizations of the world, no matter how you slice it – in terms of art, technology, wealth, military power, population, area controlled, or influence on world history. The people of the Andes independently invented agriculture, domesticating the potato, the llama, and the guinea pig in the process. They devised a complicated sense of astronomy, a system of writing involving knots and strings, complex suspension bridges that defied what the first European conquerors thought possible in the realm of engineering, and a whole social and economic system that stands alongside that of any other developed society in the history of the world.

And yet….

Any officially-adopted textbook I have ever been issued was nearly silent on these subjects. Best case scenario, the world of the Inca has been granted a sidebar mention – couple of paragraphs to summarize a whole people. Doesn’t this absence in our classrooms create a bias in the minds of students? Does it not suggest that there are certain “real” civilizations – the Greeks, of course, and the Romans, the Harappan civilization – and that others outside the so-called canon made a nice effort, but are somehow secondary?

This is a problem not just for the descendants of the Inca, but for all of us.

Perhaps the Greeks have influenced life in the United States more than the Inca have, just as the Harappans have shaped life in India. But perhaps this is, in part, a self-fulfilling prophecy, as the philosophies and achievements of the ancient Inca and their progenitors continue to be ignored and dismissed today – just as the Spanish ignored and dismissed them 500 years ago.

We aren’t showing these things to our students because the companies that devise our textbooks aren’t including them, because committees that develop educational standards are mired in a nationalistic view of the world, and as a result – we are missing opportunities, erasing whole chapters from the book of human history, and denying our expansive human heritage.

I am not Inca, but as a traveller, freed from the textbook, I am their student.

U.S. Senator J. William Fulbright was a complicated man. I certainly don’t agree with many things he said or did, but one thing I do admire: he recognized how important travel was for fostering educated, humane minds. At the end of World War II, he proposed allocating some of the funds derived from the sale of military surplus to implement a scholarship fund for international exchange between the United States and the nations of the world. It was on this auspicious occasion – the founding of the Fulbright Program – that he declared his aim: “To bring a little more knowledge, a little more reason, and a little more compassion into world affairs and thereby increase the chance that nations will learn at last to live in peace and friendship.”

That’s certainly the spirit that travel awakened in me. After years of feeling caged in my classroom, I suddenly felt free – to roam the world, to bear the lessons learned abroad home as souvenirs for my students. I forgo many other luxuries in order to travel extensively during school breaks, but more increasingly I have found that there are a number of professional development grants available to support my habit.

My students don’t have the money to travel with me physically, but my website: Openendedsocialstudies.org – has proven to be the next best thing.

Openendedsocialstudies.org is my public library of free geographical, historical, and science-related classroom materials and lesson plans. I use it in my classes, and since I launched it in 2015, lessons from the site have reached tens of thousands students and teachers around the world. That would be teachers like you – those not content to teach to the test, not content to be bound by tradition. The future of our planet is open ended – social studies education should be, too, arming students with tools of reason, discernment, and critical thinking. With these Open Ended lessons, I am trying to capture a sense that the world beyond the classroom is real, immediate, and relevant. A sense that you and your students have been there.

My lessons pack a lot of history and culture into digestible, media-rich bites, full of photos, videos, and granular details that you’d otherwise know only if you’d been there – but what sets them apart is that there are no multiple choice questions here. For me, visiting a country raises as many questions as it answers, and that’s how I have structured every lesson – as a segue for reflection, discussion, and further research. My lessons also aim to cultivate a greater sense of empathy and global citizenship, just like Senator Fulbright suggested when he founded his namesake scholarship (which, incidentally, has programs open to Indian educators). It’s this spirit – more so than any specific facts about the length of the Great Wall or China’s GDP – that I hope to impart upon my students.

The best thing would be to take your students on a fieldtrip every day – a world tour that throws light on experiences that most of your class can scarcely imagine. But of course, for so many reasons, that isn’t possible.

In the meantime, we educators have a duty to report the world back to our students – in all its unvarnished wonder. The great Mark Twain wrote, “Travel is fatal to prejudice, bigotry, and narrow-mindedness, and many of our people need it sorely…”

Are you teaching with the spirit of a traveller?

The author is a writer, educator, and adventurer. When he is not travelling to some far flung corner of the Earth, he resides in Florida with his wife and daughter – trying to leave the planet a little bit nicer than he found it. He can be reached at tkenning@gmail.com.