Sheel

English occupies a special place in India: a language that came to us from a different land, it is one that began to be taught in our country even before it became a subject of study in the country of its origin, one that became a link between different regions of our country, one whose study is deemed so important today that most Indians aspire not only to learn the language but also to use it in their ordinary, everyday lives. If many of us today find ourselves far more at ease with English than with our own languages, and often read and enjoy the literature(s) of our colonising ‘mother’ country and other countries, including our own in English translation with far more enjoyment than we do our own languages, it is because of having had not just competent but adept teachers who took great pains to ensure their wards’ mastery over the language.

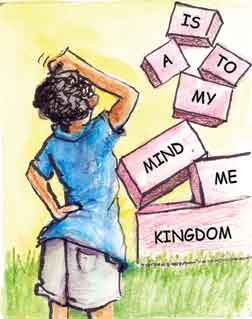

Unfortunately, with the great demand for English and the proliferation of “English medium” schools, the standards have fallen. Examining the way English (or any other language, for that matter!) is taught in our schools today, one major problem that I see is that literature and language are viewed as two different areas of learning that need separate lessons, and as often as not, different teachers are assigned to teach English literature and the complex structures of the language (which are commonly designated ‘grammar’ or ‘grammar and vocabulary’), particularly in the higher classes. In my opinion, the separation of language lessons from literature is an artificial one that negatively affects children’s understanding of the language, and is responsible for the lack of fluency in many learners of English.

Unfortunately, with the great demand for English and the proliferation of “English medium” schools, the standards have fallen. Examining the way English (or any other language, for that matter!) is taught in our schools today, one major problem that I see is that literature and language are viewed as two different areas of learning that need separate lessons, and as often as not, different teachers are assigned to teach English literature and the complex structures of the language (which are commonly designated ‘grammar’ or ‘grammar and vocabulary’), particularly in the higher classes. In my opinion, the separation of language lessons from literature is an artificial one that negatively affects children’s understanding of the language, and is responsible for the lack of fluency in many learners of English.

To elaborate further, some of the key assumptions that I find involved in the separation of language and literature lessons are: one, that the structure of a language and its literature can be taught/learned independently of one another; two, that language can be better understood and used by learning the rules behind its complex structures; three, that while literature uses words in different ways, it is not necessarily a fit medium to examine and study the structure of language; and four, that therefore the two may with no trouble be assigned to separate instructors with different kinds of competencies.

The author is a writer and editor who also conducts workshops for teachers and children. She may be reached at sheel.sheel@gmail.com.