Aruna Sankaranarayanan

Last month, I delineated the skills and dispositions that children acquire when they engage in the visual arts. In this, the second of a four-part series on creative pursuits, I discuss the benefits of music on developing minds.

Before diving in, I am compelled to address the brouhaha caused by the misreporting of a study involving music and cognitive performance. In an article on bbc.com, Claudia Hammond, describes how the “Mozart effect” garnered public attention after a study published in Nature in the nineties found that students did better on visuals-spatial tasks after listening to 10 minutes of a Mozart sonata relative to two control conditions of listening to silence or a set of instructions for relaxation. This finding was subsequently misinterpreted by the popular press to mean that listening to classical music makes you more intelligent. This then spawned frenzied marketing with parents buying into the notion that listening to classical music makes infants smarter.

While research doesn’t support the idea that listening to Mozart, or any other music, for that matter, boosts your IQ in the long-term, learning music, either vocal or an instrument, can bestow a number of advantages on the learner. In his book, This is Your Brain on Music: Understanding a Human Obsession, music aficionado and neuroscientist, Daniel Levitin describes how his own auditory perception grew sharper and more nuanced with training.

Music engineer, Mark Needham, showed Levitin how different microphones, including their placements, can alter sounds. Initially, Levitin was unable to discern differences but gradually he was even able to discriminate “between one brand of recording tape and another.” Expert musicians can tell the difference between two brands of violin after just listening to a couple of notes. Just as exposure to the visual arts enhances visual perception, musical training accentuates our auditory experiences.

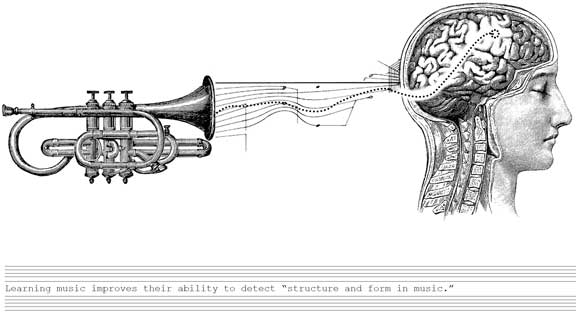

Another popular myth that Levitin busts is that music primarily engages the right hemisphere of the brain. According to the author, listening, performing or composing music involves almost “every neural subsystem.” Of course, different aspects of music are handled by different regions. For example, playing an instrument activates the cerebellum, the brain stem, the motor cortex and the frontal lobes. Listening to music, on the other hand, triggers the auditory cortex, the frontal lobes, the mesolimbic system and the cerebellum.

Interestingly, Levitin also reports that some aspects of music processing moves from the right to the left hemisphere after formal musical training, possibly because musicians start talking about music in “linguistic terms.”

Many popular songwriters like Stevie Wonder and Paul Simon have referred to their works as “sound paintings.” However, unlike paintings, music is dynamic as it changes with time. While it can be argued that visual perception also undergoes shifts if we stare long enough at a painting, a sense of time in music, conveyed through rhythm and meter, is absolutely essential.

Levitin maintains that when children receive music training, even for a short period, it engenders brain “circuits for music processing” that are more effective compared to those who don’t undergo training. Learning music, in any form, enhances children’s listening skills and improves their ability to detect “structure and form in music.” Harvard neuroscientist Gottfried Schlaug has found that the corpus callosum, which connects the two hemispheres of the brain, is bigger in musicians than in lay people, especially if they received early training.

Research also supports the idea that regardless of your talent, effort is essential to becoming a musician. One study found that the brain region that controls the movement of the left hand increases in size as a result of violin practice. While we cannot discount the fact that some people are endowed with a genetic proclivity towards playing an instrument or singing, they too need to persevere to attain expert levels. Even Mozart, who is known for his prodigious talent in music, wrote his best pieces only after receiving around 10,000 hours of practice.

According to Levitin, becoming a musician involves gaining a cluster of component skills. These include eye-hand coordination, muscle control, motor dexterity, memory for musical structures and patterns, grit and rhythm. Musical expertise can thus assume different forms depending on an individual’s unique constellation of skills. But at its core, music is about having an emotional experience.

Like artists who convert lines and circles into forms, musicians use the fundamental elements of sound, i.e., pitch, loudness, tempo, timbre, rhythm and reverberations to create more complex amalgams like harmony, meter and melody. A piece of music moves us because of the “relationship among these elements.” Levitin concedes that many art forms, like painting, dance and music, are created from basic attributes that are combined meaningfully and aesthetically to ultimately evoke emotions in us.

Just as painters and sculptors express themselves through works of art, musicians may convey “an aspect of a universal truth” through their compositions, thereby touching and influencing listeners and themselves. Music is indeed a powerful, affective tool as it can sweep us through the entire spectrum of human emotion from tranquillity to rapture to anger to fear. And, in some instance, music can evoke transcendental experiences, wherein a person feels connected to a larger, sublime whole.

Thus, if children exhibit an interest in sound or music, their proclivity may be nurtured. While some children enjoy formal training, don’t despair if your musically-inclined child shuns the piano or Carnatic vocal classes. Levitin reminds us that some of the greats of Western music, including Frank Sinatra, Louis Armstrong, Eric Clapton, Stevie Wonder, Joni Mitchell and George Gershwin didn’t undergo formal training. So, if your children delight in banging on drums or belting out numbers, don’t discourage their endeavours or force them into classes against their will. Remember that you can always close the door or invest in a pair of earplugs.

The author’s forthcoming book, Zero Limits: Things Every 20 Something Should Know will be published by Rupa Publications. She can be reached at arunasankara@gmail.com.