Lakshmi Karunakaran

“Education is the process of living and is not meant to be the preparation for future living.” – John Dewey

At the turn of the mid 19th century, almost a hundred years after Europe transitioned into the Industrial Revolution, the education system in India was primarily made of a wide network of small community based schools – pathshalas, gurukuls and madarasas. This indigenous education system, however, was considered unnecessary and redundant by the British who introduced a model much alien to the Indian society. Lord Thomas Babington Macaulay had said in his infamous speech, “I believe, no exaggeration to say that all the historical information which has been collected from all the books written in the Sanskrit language is less valuable than what may be found in the most paltry abridgements used at preparatory schools in England…”

The Industrial Revolution had by then changed the education systems in Europe and America. It was designed to cater to the needs of the industry – a factory model – with an emphisis on uniformity and conformity rather than personal attention, diversity and creativity. While in the real sense Industrial Revolution in India came late, mostly post-independence, a foreign education system was forced on it. It was soon clear to many philosophers and educators of the times that this kind of system promotes consumeristic and competitive values while producing individuals who are highly disciplined and conforming to hierarchies, thus in many ways reinforcing social inequalities of class, caste and gender.

Early pioneers in alternative education

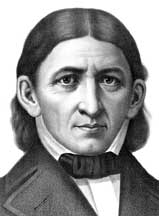

The most significant shift in educational methodology came when the focus of education shifted from the needs of the society and/or the industry to the needs of the child and its human nature. The works of philosophers and educators of the 18th century, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi and 19th century Friedrich Froebel laid the early foundation of the alternative school movement. Rousseau himself had no formal education and largely led a solitary life. His book Émile is a path-breaking book on education and promotes the idea that it is possible to preserve the original nature of the child by careful control of his education and environment based on an analysis of the different physical and psychological stages through which the child passes from childhood to adulthood. Rousseau argued that the traditional methods of schools do not focus on the child and impeded the child’s organic, natural and spiritual growth. This emphasis on the innate development of human nature became the primary philosophical basis for many alternative movements in education.

“Play is the highest expression of human development in childhood, for it alone is the free expression of what is in a child’s soul.” – Friedrich Froebel

“Play is the highest expression of human development in childhood, for it alone is the free expression of what is in a child’s soul.” – Friedrich Froebel

Inspired by Rousseau’s principles, in the early 1800s, Pestalozzi opened schools for orphans putting some of his basic principles of alternate education into action. His work inspired many educators in Europe and America including Joseph Neef, one of his disciples who founded child-centred schools in the U.S. Another teacher from Pestalozzi’s school, Friedrich Fröbel founded the kindergarten concept where children learn through fun and engaging activities like art and music by transforming playtime into opportunities to instil important cognitive, motor and social skills.

Progressive education movement

Strongly influenced by his predecessors, in the late 19th century, Fransis Parker along with John Dewey started the Progressive Education Movement. The progressive education programs emphasized learning by experience – hands-on projects, experiential learning, integration of entrepreneurship into education, strong emphasis on problem solving and critical thinking, focus on personalized learning accounting for each individual’s personal goals, integration of community services and a special focus on group work and development of social skills. Parker’s influence spread to many alternative schools during the first two decades of the 20th century, such as those associated with progressive educators like Margaret Naumberg, Helen Parkhurst, and Caroline Pratt, among many others.

Around the same time Maria Montessori, an Italian paediatrician and psychiatrist who studied child development, opened her first ‘children’s home’. In her unique methodology, Montessori encouraged children to spend most of their time in activities of their own choice and at their own pace. Rudolf Steiner, an Austrian philosopher and mystic developed a spiritual science called Anthroposophy. The Waldorf/Steiner educational model focused on creativity, spiritual values and social responsibility for the mind, body and soul. In the method, children are taught based on their own developmental characteristics. Both Montessori and Steiner methods have evolved into important international movements for educational change.

“The greatest sign of success for a teacher… is to be able to say, ‘The children are now working as if I did not exist.’” – Maria Montessori

“The greatest sign of success for a teacher… is to be able to say, ‘The children are now working as if I did not exist.’” – Maria Montessori

Alternative education, a social movement

The 1960s brought a unique turn to the history of alternative education across the globe. It was in this decade that counter-cultural themes that had always been marginal and virtually invisible – racial justice, pacifism, feminism and opposition to corporate capitalism – suddenly became visible on streets and public spaces, in the form of mass demonstrations, alternate lifestyles, books and publications. Educators and other writers – including Paul Goodman, John Holt, Jonathan Kozol, Herbert Kohl, George Dennison, James Herndon and Ivan Illich passionately attacked and questioned the role of education systems that created inequalities in society and promoted alternative education methodologies. This shook the core of the traditional education system and gave birth to hundreds of schools that celebrated Rousseau, Pestalozzi and Froebel’s ideas. The idea of ‘humanistic’ and ‘holistic’ education became popular.

Despite this turn, alternative education systems do not have widespread acceptance, especially by the state-led public education systems. While they remain a methodology that is adapted in case of special education or in intervention for children ‘at risk’, traditional values are still being strongly reasserted in politics and in education. According to Ivan Illich’s ‘controversial’ book Deschooling Society, the idea of a public-school system has outlived its usefulness. According to Illich, in a democratic, information-rich society, facilitated by mentors, children should have access to education that nourishes their diverse personal interests and styles of learning.

“Schools are designed on the assumption that there is a secret to everything in life; that the quality of life depends on knowing that secret; that secrets can be known only in orderly successions; and that only teachers can properly reveal these secrets. An individual with a schooled mind conceives of the world as a pyramid of classified packages accessible only to those who carry the proper tags.” – Ivan Illich

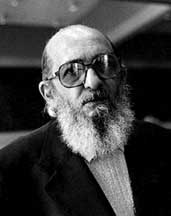

In 1968, Brazilian philosopher Paulo Freire in his book Pedagogy of the Oppressed introduced the banking concept in education. The ‘banking’ concept of education is a method of teaching and learning where the students simply store the information relayed to them. Their responsibility is to store this information and accurately recall it when necessary. They are not asked to participate in the information any other way. This method sees the world as static and unchangeable, and students are simply supposed to fit into it as it is. It prevents students from developing skills that make them critical thinkers and become part of promoting long-standing biases within society.

In 1968, Brazilian philosopher Paulo Freire in his book Pedagogy of the Oppressed introduced the banking concept in education. The ‘banking’ concept of education is a method of teaching and learning where the students simply store the information relayed to them. Their responsibility is to store this information and accurately recall it when necessary. They are not asked to participate in the information any other way. This method sees the world as static and unchangeable, and students are simply supposed to fit into it as it is. It prevents students from developing skills that make them critical thinkers and become part of promoting long-standing biases within society.

Alternative education in India

By the late 19th century social reformers like Mahatma Gandhi, Rabindranath Tagore, Swami Vivekananda, Dayanand Saraswati, Syed Ahmed Khan, Jyotiba Phule, Savitribai Phule and others promoted the idea of education as a path of social regeneration and integration. They set up educational institutions exploring alternative education methods throughout the country. Vivekananda and Dayanand Saraswati set up Ramakrishna Mission and Arya Samaj Schools with the aim of religious revitalization and social service. Aligarh Muslim University was founded by Syed Ahmed Khan for imparting modern education without compromising Islamic values. Jyotiba and Savitribai Phule actively worked on education for girls and Dalits in Maharashtra.

“The highest education is that which does not merely give us information, but makes our life in harmony with all existence.” – Rabindranath Tagore

As an alternative to the limitations of the school system set up by the British, Rabindranath Tagore set up his own alternative educational system: Vishwa Bharati in Shantiniketan, Bengal. Set in the lap of nature, classes are largely held in the outdoors and the space integrates learning with arts, aesthetics and nature. Shantiniketan was a return to the gurukul system. Gandhi’s philosophy promoted contextually relevant education, emphasis on practice rather than theory, social awareness and service, mother tongue as the medium of instruction and opposition to examination-oriented assessment of students. His vision brought alive a series of schools in Phoenix Farm and Tolstoy Farm in South Africa and later in Champaran, Sabarmati, Wardha and many other parts of India.

Providing an atmosphere nurturing independence and self-reliance was at the centre of Educationist Gijubhai Badheka’s philosophy. He gave this idea an institutional basis by establishing Bal Mandir in Gujarat in 1920. His writings, especially Divaswapna (1990), have inspired generations of educators.

Philosopher and educationist Jiddu Krishnamurti believed that the purpose of education was to bring about freedom, love, ‘the flowering of goodness’, and the complete transformation of society. Krishnamurti set up two schools in the 1930s, Rajghat Besant School in Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh and the Rishi Valley School in Andhra Pradesh. Over the decades, the KFI (Krishnamurti Foundation of India) across India and the US has kept alive his philosophy through its numerous schools.

“Surely a school is a place where one learns about the totality, the wholeness of life. Academic excellence is absolutely necessary, but a school includes much more than that. It is a place where both the teacher and the taught explore not only the outer world, the world of knowledge, but also their own thinking, their behaviour.” – J. Krishnamurthy

“Surely a school is a place where one learns about the totality, the wholeness of life. Academic excellence is absolutely necessary, but a school includes much more than that. It is a place where both the teacher and the taught explore not only the outer world, the world of knowledge, but also their own thinking, their behaviour.” – J. Krishnamurthy

While alternative education still remains on the fringes in India with a handful of schools in each state, a large population of children still attend traditional schools. However, the recently adopted educational policy, NEP 2020, has some welcome changes. Introduction of the mother tongue until 5th grade, emphasis on vocational learning, flexibility to choose subjects across streams, etc. But it’s a wait and watch to see how efficiently it will be implemented and how it will cater to the millions of children from low-income families across the country.

The author is an educator based in Bangalore. She can be reached at lakshmikarunakaran@gmail.com.