Steven Rudolph

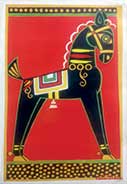

People who know me know that I have a thing for traditional craft. My office and home are a kaleidoscope of handmade items that represent the myriad local cultures from all over India – paper pinwheels from Haryana, thatch mats from Assam, ceramics from Uttar Pradesh, Madhubani paintings from Bihar, table runners from Rajasthan, and so on. I am also a huge fan of truck art and have numerous objects that have been painted in the truck art style.

What is it about craft that gets me going? Apart from making a room more cheerful and visually appealing, I believe craft holds a key to solving fundamental problems of our education system and of our society as well. You see, the tradition of craft incorporates within it a number of key values that make our society whole, but which day by day are being lost. As craft diminishes, so do these values, and the result is a world that becomes less beautiful and more wasteful. Let me explain.

What is it about craft that gets me going? Apart from making a room more cheerful and visually appealing, I believe craft holds a key to solving fundamental problems of our education system and of our society as well. You see, the tradition of craft incorporates within it a number of key values that make our society whole, but which day by day are being lost. As craft diminishes, so do these values, and the result is a world that becomes less beautiful and more wasteful. Let me explain.

First, there exists an inherent practice of sustainability in the creation of craft. These items are mainly produced from indigenous and naturally available materials – from wood, bamboo, straw, mud, stone, and so on. In other cases, craftspeople make use of recycled materials. As such, you would find nary an artisan who would subscribe to the use-and-throw philosophy – a practice that emerged from the United States in the 1930s as a response to the government’s attempt to increase consumption to spur the economy that was suffering due to the depression. Artisans see where their raw materials come from – and how hard one has to toil to acquire them. They therefore implicitly understand the value of resources, and automatically tend to preserve and recycle them.

Second, craft embodies and fosters a sense of aesthetics. Aesthetics by Western definition relates to the element of beauty that is infused into artwork. However, in the Eastern sense, the concept of aesthetics relates more to bhava, or the emotional sentiment of the artisan, whose aim it is to forge his craft item with that emotion in a manner that awakens one’s sense of humanity, spirituality and interconnectedness with our entire world. With respect to this type of artistry, there very well could be a butterfly effect (the concept that all things are inter-related so much so that a butterfly flapping its wings in one part of the world could cause a tornado in another part); it is indeed possible that a shawl embroidered by a woman in Kashmir leads to a man’s divine realization in Kansas.

Third, craft is made by hand. From an economic perspective, this provides work to craftspeople. When we mass produce, people are made redundant. When we mechanize too much of our production, we leave gaps in employment. By nurturing and valuing craft we prevent people from losing their livelihood.

The loss of appeal for craft

After so many years of exposure to the global, industrialized world, India has greatly lost its appeal for craft among the mainstream population. As the country urbanizes, people get out of touch with the world of handmade items. While shifting to cities, the younger generations aspire to a more international lifestyle. In pursuit of higher status, they reject the village life and the things produced there, considering them to be backward and inferior, instead seeking out goods that have a more global look and feel to them. But without a sense of Western aesthetics, they are lured into the world of kitsch – mass-produced objects that simulate craft. Go into any modern mall today, and you’ll find dozens of shops selling machine-made chinoiserie and culturally non-descript items that could be from anywhere – or nowhere. Such individuals are more inclined to stock their house full of tacky porcelain bric-a-brac than to adorn their living spaces with handcrafted items made from wrought iron and wood.

After so many years of exposure to the global, industrialized world, India has greatly lost its appeal for craft among the mainstream population. As the country urbanizes, people get out of touch with the world of handmade items. While shifting to cities, the younger generations aspire to a more international lifestyle. In pursuit of higher status, they reject the village life and the things produced there, considering them to be backward and inferior, instead seeking out goods that have a more global look and feel to them. But without a sense of Western aesthetics, they are lured into the world of kitsch – mass-produced objects that simulate craft. Go into any modern mall today, and you’ll find dozens of shops selling machine-made chinoiserie and culturally non-descript items that could be from anywhere – or nowhere. Such individuals are more inclined to stock their house full of tacky porcelain bric-a-brac than to adorn their living spaces with handcrafted items made from wrought iron and wood.

Why students need greater exposure to craft

Some of the greatest problems we face today relate to economic, environmental, and cultural sustainability. As educators, we make attempts to explain things theoretically to our students so that they might make the world a more sustainable place when their generation takes the reins from the current generation. However, such attempts are often superficial and even misdirected. A child who creates a diorama from thermocol to represent the ills of pollution or environmental degradation completely misses the point. And charts about recycling do little good if the student becomes a victim of the buy-and-throw culture and regularly tosses out string, rope, paper and bottles that could easily be reused to create an endless array of craft items for his home or classroom.

In addition to learning lessons of environmental responsibility and resourcefulness, children learn many other lessons through craft that the general curriculum could never achieve. By working with their hands, they learn practicality. India’s education system is far too theoretical, and individuals languish when it comes to having to do things manually. (A man with an engineering degree is loath to look under the bonnet when he faces engine problems. He instead calls an uneducated worker to fix it!) Children who learn to work with their hands are much more capable of solving problems – and even being more effective in their work. In fact, many top international engineering companies today aim to hire individuals who had extensive experience in their early years creating and building things with their hands.

What is more, by being exposed to different designs used in craft, children experience the power and energy contained within the patterns and symbols that comprise their culture. The various shapes and motifs found in traditional design contain deep connections to the underlying energies of the universe, and those who understand and channelize them can attain enlightenment, the ultimate success, whether they acquire a PhD or whether they pursue a vocation without any formal education.

What is more, by being exposed to different designs used in craft, children experience the power and energy contained within the patterns and symbols that comprise their culture. The various shapes and motifs found in traditional design contain deep connections to the underlying energies of the universe, and those who understand and channelize them can attain enlightenment, the ultimate success, whether they acquire a PhD or whether they pursue a vocation without any formal education.

What I would like to propose, therefore, is greater inclusion of craft throughout the school’s environment and curriculum. This could be done in a number of ways:

- Invite local artisans to the school to share their craft skills with students.

- Have more craft activities within the school such as weaving, pottery, candle making, woodwork, bamboo work, embroidery, ceramic making, etc.

- Decorate walls with murals using various artistic styles, such as Warli, Madhubani, Gond, and Bhil.

- Create mosaics on walls using waste stone, glass, and tiles.

- Sell student-made craft items at school events to generate revenue for the school.

- Have students from higher classes make craft toys for students in lower classes.

In short, I believe that craft can do wonders for schools. With respect to interior design, it can significantly enhance the décor of the school atmosphere. In the hands of students, it can awaken a dignity of labour within them, and get them to appreciate their indigenous culture and design. Further, it enables them to get closer to the natural resources used to produce things, which has potential for inspiring recycling and reduction in wastage and mindless consumption. And most importantly, I believe that this spirit of handmade and “heartmade”, can inspire personal transformation and social cohesion, the likes of which have not been seen since factory-style education was introduced in India in the mid 1800s.

I have created a blog dedicated to inspiring the use of craft at Jiva Public School. (http://designatjiva.wordpress.com). There I have captured craftwork in many schools from all over India that are doing amazing things with craft. I welcome you to share your ideas with us and explore how by embracing craft, we might craft a more beautiful and sustainable India.

The author is Director of Jiva Institute, Faridabad. He can be reached at steve@jiva.com.