Tanaya Vyas

When I was in the 9th grade, I had the chance to participate in a study-trip to a wildlife sanctuary. I remember the day when a classmate began chatting with me about the week-long trip being arranged by our school. Excited to be heading out of the classroom, he spilled out all his plans. He said he was already armed with packs of potato chips and an audio-player and was looking forward to buying some laser pens very soon. “It will be fun to flash the lasers around while we go on the jungle trail at the sanctuary!” he said.

A few years ago, this memory from my 9th grade flashed in my mind while I was briefing a batch of university students for a study-trip to a village in Rajasthan. As we began the pre-field orientation, students’ questions popped up. “Can we carry instant-noodles?” “Will there be hot water at the dorm for bathing?” “Can my brother come along too?” Perhaps just like my friend from the 9th grade, these students were not sure of what to expect at the site. If not sensitized to the contextual aspects of the sites, students might perceive an educational field excursion to be a “picnic”.

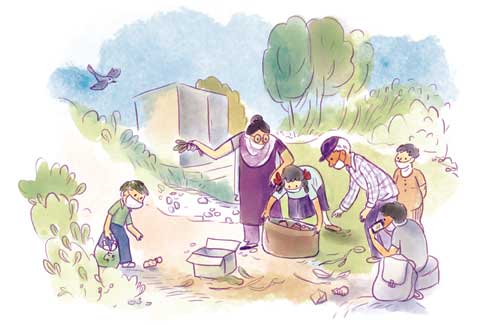

There was a need to better prepare them towards understanding and appreciating various aspects of that place. At the village, the student who was concerned about the availability of hot water went through what he called a ‘life-changing’ experience. Carrying large vessels of water to the chulha and waiting patiently for the water to heat up, cleaning one’s dishes after lunch and clearing the trash from one’s room were few instances that left the students craving for the comfort of their city abodes. Every morning, the students ventured into the inner streets of the village with their sketchbooks and journals, only to encounter new adventures at every step. Walking in the middle of the street unaware of the cattle returning in the evening, was just one of the many incidents that invited stern gazes at the bunch of chaotic ‘student guests from the city’. As a facilitator, a few issues that I decided to keep in mind for various phases of the trip helped me plan the student experience better amidst all the chaos.

Whether at the university or school level, student awareness of the context is an important aspect to consider when planning outdoor learning experiences. Educational excursions might remain a meaningless endeavor if the participants and facilitators stay oblivious to the academic, cognitive and social goals of such engagements. Field and community based activities have been regarded as powerful learning resources in school curricula. In educator David Sobel’s words, “Wet sneakers and muddy clothes are prerequisites for understanding the water cycle.” Outdoor learning encourages the learner to view the world with fresh perspectives and relate the concepts in the syllabus to real life. Field-based activities, however, require extensive planning and monitoring by the facilitator. What is often underestimated is the need to orient the participants for conscious conduct towards the site’s local context and discuss learners’ concerns before entering the field to make the experience more meaningful.

Challenges associated with field-based learning may include aspects such as learners’ over stimulation as they encounter new surroundings, limited time for the learner to absorb new information, difficulties faced by the teacher in preparing suitable tools like worksheets to aid learning, unexpected events or interactions and so on. Yet, guidance towards facilitating field- engagements often ignores the crucial aspect of inculcating socio-environmental sensitization and responsibility within the learner. I found myself asking certain questions while planning the field trip to the village in Rajasthan: Will the students be able to adjust to the new environment? What can I do to help them have meaningful interactions at the site? Can I prepare any material to enrich student learning both at the site and after we return?

Selecting the site

Your motivation towards selecting a site could determine the first level of planning. Does this site fulfill your purpose? Does it have a specific program already being run which might be helpful for the students to connect their field learning with the class curriculum? Would the students be engaging in any local activities? Are there any resource persons you might get in touch with? Suppose you have recently taught the topic, ‘agriculture’, can your students work with a local expert to understand the process of farming? Maybe your theatre students could get a chance to learn local drama culture and techniques? You may prepare a list of questions for the local experts or administrative staff that can help you with planning engagements and resources you can share with your students.

Site familiarity

You should visit the site before taking the students, if possible. This can help in deciding specific areas as per the study requirements. Are there certain regions that need to be avoided in the interest of student safety? Are there any possible distractions you think might crop up? This practice can assist in managing time and energy better when the actual trip takes place. Showcasing the field plan and locations through a film or photographs to the students can also reduce some initial apprehensions they may have. Sharing such details could also promote deeper student-teacher interaction before the trip. The students can be asked to write their expectations and impressions of the place before the trip. By the end of the trip, they can compare their pre-field expectations with their on-field notes to mark new learning.

Sharing goals and expectations

In order for the students to prepare for the trip, you might wish to take them through the concepts from the past courses. You may plan an exercise wherein they note the major themes covered in earlier course work and questions they might have encountered regarding new topics. Also discuss any rules, expected dress code, language specifics if any, health and safety issues, photo or videography permissions, and other essential information to make the students comfortable with the social and environmental particulars of the site. A meeting may also be arranged with the guardians of the students to discuss any queries and share documents containing the trip schedule along with consent forms.

You can also appoint some students as the group reporters to take responsibility by turn. They can communicate student concerns to the teacher while on the trip. This session could be a good opportunity to make the students aware of their responsibility towards the local environment and respecting other people’s time, privacy and space. A post-trip activity plan is ideal to be shared during the student orientation phase, so that the students are ready to organize their work accordingly.

On-field exercises

Field journaling is a popular exercise, but at times the students are hesitant to draw or write in their journals. As the students might be distracted by unfamiliar situations at the field site, sketching as a way of practicing observation skills could be nurtured much before the field trip. To ease their initial apprehension, the students could be taken to nearby museums, artisan workshops, parks, etc., for on-location sketching practice.

You can introduce them to methods like visual mapping of an area along with its landmarks and routes, noting sensorial information such as smells and textures, keeping track of key information found at the site and practicing rapid sketching of human activities. You can ask the students to focus on an object and trace its historical and contemporary uses through interactions with the local people. You may prepare worksheets based on such exercises.

The above exercises can be done in small groups to encourage peer learning and communication. The students can also be given individual themes to work on to support independent exploration. By the end of the day, students can be encouraged to discuss their findings, explorations and questions. In a virtual scenario, the students may be guided to create podcasts out of their discussions.

Encouraging collaboration

Students can also be involved in areas of planning and organizing some aspects of the trip. You can distribute responsibilities across students and ask them to keep track of their tasks. You may even make good use of moments when the group is in need of a break from intense activities like hiking. During such a break, you could keep some worksheets ready which the students could use to reflect on acts of collaboration, gratitude and their interactions with local communities and environment.

Post-trip exercises

Echoing Honey Vahali’s words from A Song Called Teaching, the process of reflection is essential to experiential pedagogy. Students can tie their field-learning to smaller city-trips to reflect on similarities and differences in their experiences. Additional time can be given for consolidating their notes, diaries, logs, journals and any other material to curate in the form of an exhibition, printed document or book which can later be added to the school library for further reference. Thus, the field experience could extend to the classroom. The students can be asked about their overall comments, challenges and learning during a debriefing session. They can also be engaged in a task to demonstrate their new knowledge.

The current pandemic circumstances have brought new challenges and opportunities to learn from uncertainties. Most of the non-classroom or ‘field’ learning for the students is taking place in their home-kitchen while trying out a new recipe, listening to stories from elders, tending to the plants in the balcony, interacting with the neighbours from across the verandah or observing the night sky from the rooftop. During such activities, students may be frequently using digital media as part of their assignments. They can be made aware of media recording and content sharing guidelines, and you may prepare a private online space for uploading their work.

Across physical as well as virtual field experiences, both students and teachers need to stay empathetic and open-minded. Field experiences of the future should provide opportunities that enable students to be mindful of the world within and around them.

Acknowledgement: Sincere gratitude to Dr. Girish Dalvi, Faculty Member, IDC School of Design IIT Bombay.

References

• Sobel, D. (1999) Beyond Ecophobia: Reclaiming the Heart in Nature Education. Orion Society

• Vahali, H. (2019) A Song Called Teaching: Ebbs and Flows of Experiential and Empathetic Pedagogies. Aakar Books

The author is a doctoral student at the IDC School of Design, IIT Bombay. Her research interest lies in the area of design for environmental literacy (instead of learning). She can be reached at tanaya321@gmail.com.