Ritesh Khunyakari

The wide coverage of students’ achievements in news media, advertisements, and reports after the board exams underscores the significance that society attributes to one-time performance. Appearing for an exam, visits to classrooms or schools, meetings in institutions give an impression of inspection and judgment. One wonders why we are not able to relate assessment to the delight of knowing what we know and what we need to know in order to work better or create spaces for enhancing learning. This article emphasizes the need for re-thinking assessment to make it informed, productive and enrich the learning experience for all involved.

Unpacking the notion of assessment

First, let us distinguish “assessment” from a related but conceptually distinct term “evaluation”. According to Rossi, Lipsey, and Freedman1 (2004), evaluation involves “a systematic process of gathering, analyzing and using information from multiple sources to judge the merit or worth of a program, project, or entity”. While evaluation enables informed judgments about programmes, their improvement, and implementation, assessment serves in decision-making by measuring performance on task, activity, project, or any specific engagement. Russell and Airasian2 (2012, p3) define assessment as the “process of collecting, synthesizing, and interpreting information to aid the teacher in decision-making.” Thus, individual or group performances are assessed and academic programmes are evaluated.

According to Tanner and Jones (2006)3, assessment is a continuous process involving three kinds of purposes: managerial, communicative, and pedagogical. Based on its purposes, assessment caters to different stakeholders – students, parents, policy makers, etc. As visualized in Figure 1, assessment is at the inter-junction of these three primary purposes. Often, some purpose gets emphasized while others get compromised. A balance between purposes needs to be sought, which perhaps could be built on an understanding of the forms of assessment.

Forms of assessment: A bird’s eye-view

If we were to consider the different ways of assessing, we find ourselves to be struggling with dichotomies. Table 1 captures the various schemes and ‘dichotomies’ in use. The bi-directional arrow indicates continuity and variation within a scheme. Often, there is a confusion between a scheme and a form which leads us to mixed ideas. Making explicit the feature underlying a scheme and its corresponding dichotomous forms clarifies at least two things: (a) the assessment forms (represented as ‘defining dichotomy’) mirror the underlying feature (purpose), and (b) the continuity between a dichotomy implies that items representing both forms can be used in the same assessment tool. Let us tease out the meaning we relate with each of these forms.

Declarative assessments judge factual content about places, people, events, concepts, etc. The State and National level examinations assess declarative knowledge. In contrast, procedural assessments test the ability to use declarative knowledge, either articulated or performed steps in context of a technical, vocational, or skill-oriented activity. The forms may be used either individually or in combination, depending on any of the three function/s that it needs to achieve. For instance, students’ understanding may be assessed for declarative knowledge with questions inviting them to describe, explain or argue. For example, describe the process of osmosis. One can assess students’ procedural knowledge as well as declarative knowledge by asking students to engage and infer from a practical activity or experiment.

Figure 1: Interplay of different purposes of assessment that meet needs of stakeholders involved in education. Notice the triangular interface suggesting a balance of purposes.

Content-oriented learning privileges retrieving information and conceptual organisation. Students’ knowledge gets equated to the ability to recall content, as in questions seeking descriptions, principles, and functions of different kinds of levers. Application-oriented assessment invites students to appreciate how an idea, concept, rule, or principle extends to a particular context or can be exclusively applied. Though this scheme gels with the earlier scheme, information-oriented assessment need not necessarily be declarative or procedural. For instance, students’ ability to use the given information about soil to map the distribution patterns in a region are not exclusively probing their declarative knowledge or procedural understanding. Both forms are geared towards accountability of learning experiences, serving managerial and communicative functions.

Another scheme with ‘knowledge or skill seeking’ orientation is the objective-subjective dichotomy based on the nature of questions used to elicit responses. In large-scale testing, where efficiency and consistency in marking is desirable, an objective-based format is used in competitive exams. Question formats as multiple choice, true/false, matching options, etc., enable computerised administration, saving considerable expense and human effort. In contrast, subjective form affords questions with more than one response, descriptive essays, analysis, comprehension, etc. Though prone to the assessor’s biases, time-consuming and labour-intensive, this form is preferred to assess critical thinking, skills of knowledge transfer, knowing about creative imaginations, etc. While the objective form serves largely the managerial function, the subjective has potentials for meeting pedagogical and communicative functions.

Formal-informal dichotomy, like the earlier schemes, probes ‘knowledge and skills’ but differs in placing substantial thrust on context in which probing is embedded or an outcome is expected. Formal assessment requires an advanced intimation to learners and relies on tools such as tests, quizzes, paper-pencil tasks. Performance achievement is expressed as a numerical score or a grade. On the other hand, informal form involves contexts not pre-defined either by assessor or learner. Examples include rating scales, inventories, observational records, portfolios, rubrics, etc. It differs from earlier schemes in its focus on communicative and pedagogical functions.

Table 1: Schemes of assessment based on their features and ‘defining dichotomies’

The next two schemes are widely used to ‘map learning’. Table 2 summarizes the differences in the formative-summative scheme. While the formative addresses all the three functions, the summative addresses managerial and communicative functions. Often, teachers and teacher educators erroneously equate formal to summative and informal to formative assessment. As will be evident, the two schemes are different and distinct ways of understanding an individual’s performance.

Table 2: A comparison of the Formative-Summative forms of assessment

Last of all schemes, is the dichotomy of referenced and non-referenced kind. Non-referenced is based on judging the appropriateness of response by experts, whereas referenced relies on a yardstick or reference framework for assessing learning and is of three sub-types: (a) Criterion; (b) Norm; and (c) Ipsative.

a) Criterion-referenced implies anticipating the extent to which learners accomplish pre-defined and absolute criteria, standards for successful performance. Rather than comparing performances among students, minimum competency levels are set and no ceiling is maintained on the number of students awarded particular grade or marks. Example, driving tests for learners. The design allows comparison across settings and addresses largely the managerial and communicative functions.

b) Norm-referenced involves measuring achievement in relation to all students taking the assessment, allowing assessors to rank students in terms of their achievement and segregate them into categories of performance grades. For example, class performance for students can be marked as average for a score of 45 on 100, as ‘below average’ for less than 45 and ‘above average’ for score above 45. Standards of achievement adjudged may vary every year based on the quality of cohort performance. Such an assessment primarily addresses communicative and pedagogical functions.

c) Ipsative (Latin root, ‘ipse’ meaning ‘self’) assessment engages learners to identify their initial conditions and set achievement targets, either for the same domain or across domains, for a time period. Learners have clarity about the purpose/(s), the focus of learning, and criteria that will help them map their own progress. Students not just know what they learn but also reflect on how they progress in their own learning. These features constitute the ‘metacognitive awareness’, making this assessment remarkably distinct and primarily addressing the pedagogical functions.

In reality, one finds a perplexing mix (rather than an informed blend) of schemes, often leading to confusion in use of terminology, tools, and in interpretations about achievement. For instance, the practice of unit tests as formative and final exams as summative assessment has now turned into a frozen structure for examinations. The system of marking is so entrenched that it impedes any fruitful deliberation on alternative ways of assessment. Is the problem constituted by how our educational systems function or does it relate to our negligence towards the value of assessment in learning?

In India, learning is assessed largely through paper-pencil tests and alternate forms get ignored as having ‘non-scholastic’ or ‘co-curricular’ property. A tacit tension exists between understanding the kinds and purposes of assessment and the extent to which a teacher skilfully uses assessment for enriching learning. Mere understanding of forms and tools for assessment are insufficient to circumvent the age-old challenge of using assessment in a non-threatening and resourceful manner. Drawing from experiences of research and practice that envisaged assessment as integral to learning will help initiate informed assessment practices.

Insights from research

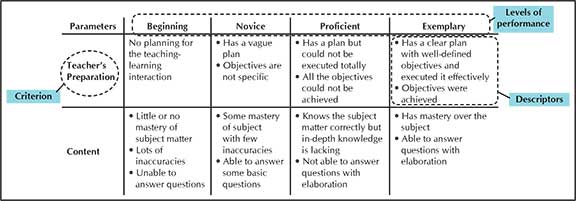

One of our studies, invited teacher educators to develop rubrics for assessing classroom teaching. The rubrics they designed were richer than either check-list or objective-template conventionally used for assessing teaching practice. They were now able to map the level of teacher’s performance and indicate what could be done further to improve his/her performance. Figure 2 presents an excerpt of a rubric developed by a group of four teacher educators which include: (a) criteria that indicate specific attributes for assessing product, process, or performance e.g. teacher preparation; (b) levels of performance are ratings that differentiate extent of quality of product, process or performance through qualitative labels, points or scores. Example, beginning-novice-proficient-exemplary; and (c) descriptors are brief, textual narratives describing indicators for judging work across criteria and performance levels. Example, [Teacher] has clear plan with well defined objectives, executed it effectively, objectives were achieved. Based on rubrics, teacher educators were able to specifically locate the quality and possibilities in practice and deliberate on their own learning. Encouraging assessors to generate criteria organically increases the ownership and engagement in assessment.

Figure 2: An excerpt of a rubric developed by a group of teacher educators

Multiple modes of assessment

A single mode of assessment is often insufficient to measure students’ understanding. The same test item may yield an entirely different gamut of responses. Appreciating students’ expression through several modes, over periodic intervals, could reasonably gauge learning embedded in their contextual realities.

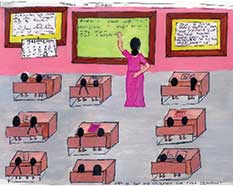

Figures 3 and 4 illustrate that though both girl students, from the same age group made a poster on “Images of Science”, their depictions represented different ways in which they related to science4. Depictions may deviate from anticipated criteria yet reveal interesting associations that tailor learning and invoke meaningful learning among students. Multiple modes or forms may help establish cross validation across forms of assessment.

Figure 3: A school girl’s depiction of “Science” relates to her personal experience of a science classroom. Notice attentive orientation of equal number of boys and girls, to a female science teacher using ‘chalk and board’ pedagogy.

Figure 4: Another girl’s depiction of “Science” is about the consequences of science. Notice demarcation between ‘the bloom’ and ‘the gloom’ brought out through physical artefacts, emoticons, shades and hues in colouring.

Planning assessments for progression rather than event performances

Time-frozen examinations cannot build on prior experiences. Continuous, periodic assessments allow individuals to refer his/her current achievement to earlier performances. Maintaining records which document previous achievements (in form of portfolios) help revisit various phases in learning and informs current action. Progression becomes evident rather than punctuated by objective grades or marks, disconnected in time and space. At this juncture, it is important to reiterate that both ‘assessment of progression’ and ‘assessment of event performance’ are important in their own right. Assessment of progression is inevitable if continuity in learning is desired.

From teachers to students and peers: Envisioning a shift

For a teacher, giving regular, detailed feedback to the entire class is an added burden and becomes a ritual to be accomplished. If students are trusted with the role of assessing their peers, the task could transform into a reflective, critical learning engagement. Students own the process of their learning and with some guidance are not just able to assess but also gain opportunities to learn from others’ achievements. The drudgery of a burdened teacher may metamorphose into space for intense learning inviting negotiation of meanings, metacognitive reflection and critical appreciation.

From objective frozen standards to critical, generative norms

Objective, frozen standards segregate individuals. Encouraging critical, generative norms derived from experiences of individuals promise turning assessment into a humane activity. The fierce competitive atmosphere needs to reconfigure itself into an agency for critical reflection. In a study with middle school students5, we found students generate novel criteria and articulate strategies for improving their performance. Learner owned assessment surely sets critical milestones for learning!

In this article, I have argued the need for re-looking at assessment not just for summarizing knowledge and conceptual grasp but also for informing learning. The tripartite notion of assessment of learning (summative assessment), assessment for learning (formative assessment), and assessment as learning needs to be tapped. What could be the means by which we could achieve this? The article favours using multi-modal approach to assessing learning and emphasizes the usefulness of shifting the locus of who assesses learning: from teacher (authority) to students (learners) in a learning environment. Such a shift would contribute immensely to raising the ownership of learners in learning and easing the burden off the teachers.

References

- Rossi, P., Lipsey, M., and Freedman, H. (2004). Evaluation: A systematic approach. New Delhi: Sage Publications India Pvt. Ltd.

- Russell, M. and Airasian, P. (2013). Classroom Assessment: Concepts and Applications. New York: McGraw Hill.

- Tanner, H. and Jones, S. (2006). Assessment: A practical guide for secondary teachers. Continuum Press.

- Mehrotra, S., Khunyakari, R., Chunawala, S., & Natarajan, C. (2003). Using posters to understand students’ ideas about science and technology. Technical Report No. I(02-03). Homi Bhabha Centre for Science Education, TIFR, Mumbai, India.

- Khunyakari, R. (2015). Experiences of design-and-make interventions with Indian middle school students, Contemporary Education Dialogue, 12(2), 139-176.

The author is a Faculty at the Azim Premji School of Education, Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Hyderabad. He can be reached at ritesh.k@tiss.edu.

Related articles

The pros and cons of outsourced testing

Grading as a number-crunching game

How do we assess art?