Usha Raman

Less than three decades ago, most of us got our news of the world – and our more immediate geographies – from just two or three sources that we trusted implicitly. There was the morning newspaper that dropped faithfully at our door, with headlines that announced the major developments and editorials that made sense of it all. Later in the day, there was the news on the radio, read authoritatively by a deep-voiced announcer who gave us the unadulterated (though carefully selected) highlights of the day. In the evening, after dinner, families who had television sets gathered around to get some glimpses of events from around the world. The line between fact, opinion, and fiction was clear. We read slowly, we watched at leisure, and we had enough time to discuss and digest it all.

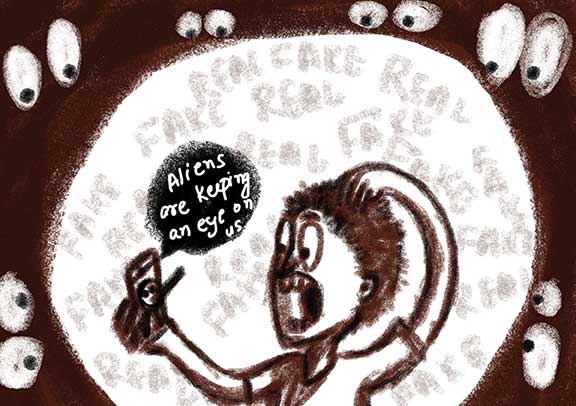

Super-fast forward at 16X speed to the present times. Our phones ping insistently even as we hit the snooze alarm, telling us that there are several alerts on our news feed. Our WhatsApp notifications bring us information about friends, relatives and the world in general, depending on what people choose to share. And on Facebook, posts from our friends, family, and a variety of commercial online outlets build our world and tell us you what to care about.

The speed at which information rushes at us makes it difficult for us not only to give attention to it all, but also to decide what is important or trivial, reliable or not, biased or fair. Media literacy in general has been considered an important skill for us all, and particularly young people, to develop in this information and media-saturated age. Young people get much of their understanding of the world from digital media, so it is important that they understand how to differentiate between sources of information, and develop the capacity to decide what to believe and how to use this information for productive purposes.

Why is it important?

Media literacy in general implies building an understanding of how media works, and the capacity to “read” media critically and intelligently. We tend to believe the media because we assume that journalists are professionals who know how to get at the truth and that they follow an ethical code that makes them responsible to give audiences unbiased and unvarnished information that is in the public interest. If this were the case, then there would be no need to arm ourselves with a special kind of literacy.

It is true that ideally, journalism should give us trustworthy information. Good journalists and media organizations do strive to give us well-researched stories, which as Pulitzer-winning reporter Carl Bernstein said, “are the best possible versions of the truth”. They check facts and make sure that opinion is clearly flagged, so that readers can distinguish between news and views.

These days, however, commercial pressures have led to a compromising of these standards, and often views are paraded as facts, and the reader is left – often intentionally – with a confusing picture. To gain audience attention, media outlets sometimes resort to manipulation and exaggeration, leaving the wrong impression among viewers and readers. To get a complete – or somewhat balanced – picture we need to look at multiple sources and piece together the “truth” by comparing different versions. But we can only do this if we approach the news media with a healthy dose of skepticism, as well as an appreciation of how the news business works.

But when it comes to information online, we have an additional problem – much of the “news” that comes through social media, on platforms like WhatsApp and Facebook, is not your conventional journalism. It is often not generated by professional journalists, but by ordinary people who come across something interesting and want to share it with others. There are also many groups and individuals who want to influence people’s thinking, so they post material that is one-sided, incomplete, or even false just to promote their agenda. A recent example is a video clip about child abductors in Gujarat that was circulated on WhatsApp, which created a lot of panic and led to some violence. It turned out on closer examination that the clip was part of a longer public awareness campaign about child safety, and had been manipulated to generate panic and foment hatred against a particular community. But the damage had already been done, as thousands of people had forwarded the clip to their WhatsApp groups.

If we are to tackle the phenomenon of fake news with education, then we have to go beyond the usual media literacy approaches, to understand the mechanics of information production and dissemination on the web. It’s also important for us (adults and children) to understand how our social life is slowly being changed by digital media.

The digital complicates things

What’s your first response when you receive a funny, interesting or curious message on social media?

Is it to just read it, laugh (or not), and then get on with your day?

Is it to immediately forward it to others in your contacts list?

Is it to think more about it and act on the information?

Research has shown that our behavior on social media is – no surprises – to be social. Depending on the kind of information we encounter, the instinct is to share it with others for one of several reasons, ranging from a desire to impress to an instinct to warn to simply mark one’s presence in a community. This makes us often share information without really considering its quality or the veracity, or stopping to think about its possible impact.

The impact can range from the negligible (others may just get irritated with this constant sharing) to the mildly negative (creating arguments and friction in family and friends groups) to the outright dangerous (if the information is sensitive or alarming). It could, over time, also build false impressions about people and issues, and strengthen stereotypes or prejudices.

One of the major underlying factors that aggravates the dissemination of fake news is our own behaviour on these social media platforms. Get the children to do a simple reflective exercise. Ask them to think about their own sharing behaviour over the past one week. What kinds of posts did they share? How would they rate the impact of this sharing? Ask them also to talk to their parents and other adults at home about their own approach to sharing posts on social media. They could then share their observations in class and discuss the implications of our sharing behaviour. What are the positive and negative aspects?

The Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism in their 2018 report noted that older people were more likely to believe content on social media than those in their teens and twenties, and were also more likely to share such information. The children, in their interviews with adults in their families, may also find that this is the case. It’s certainly something to talk about!

“Reading” into digital information

A good, credible news story is structured in a specific way. It is clear and well written, and points to verifiable sources, particularly when there are important facts to be presented. Opinion is always attributed to a source.

Use a simple news report from the daily paper to illustrate this point in your classroom. Ask the children to read the report and underline the sources, and to try to differentiate fact from viewpoint. What makes the story believable and where does its authority come from? What are the conventions that tell you that it is a legitimate piece of news? (It mentions place of origin, gives names and designations of sources, the facts are attributed to either individuals or institutions.)

Now let’s take this story that did the rounds some years ago and was established as fake:

Recently, a 21-year-old girl, while attending a barbecue party, suddenly felt an intense pain in her eyes and began screaming for help, unable to explain what was happening. She was rushed to the nearest hospital where, on examination, the doctors declared that her contact lenses had melted and damaged her eyes irreparably, thus blinding her for life.

“Contact lenses are made of plastics,” said Dr Dinesh Bhargav of Bright Eyes Ophthalmic Clinic, “And exposure to intense heat can cause them to melt.” The girl had been standing close to the grill and according to her friends, had been looking directly at the flames while chatting with her friends. “It all happened so suddenly, she just started screaming, and we didn’t know what was happening!!,” said her friend.

Most of the large eyewear manufacturers make a range of lenses, some of which contain lower grade plastics, which may be affected by direct exposure to intense heat, say experts. The companies have refused to comment, but independent medical practitioners agree that low-cost lenses can present risks to wearers.

Ask the students to identify the clues that hint to its “fakeness”. Would they believe it? Why – or why not? (This could be an exercise for the science class – many fake forwards are about non-science!)

Among the problems with this story are that it does not give any clear dates or locations for the incident. It does not mention experts or manufacturers by name. These are the sorts of details journalists would definitely put in particularly if they are making serious claims of this nature.

Ask the students to bring examples of viral messages that may or may not be true and discuss what it is about these texts that make them successful as fake news. Why do we believe them? And what it is it about them that should make us suspicious?

A healthy dose of skepticism

We live in complex times, and all of us want simpler, more direct ways in which to understand the world. This is what makes us want to believe the simple messages that come to us from our trusted networks of people – even when we know that they are not themselves experts. Even though we do know that the mass media are not perfect, they do have more accountability than unsigned forwards that we cannot trace back to a point of origin.

As the example above illustrates, fake news is not only about communalism or politics. It can relate to food, safety and medical issues, even to the weather. It can affect our everyday decision-making. It’s important that we cultivate the ability to look at information critically, especially if it reaches us through the speedy and convenient means of a social media platform – where the cost of dissemination is a click and the price of reception is a swipe.

Related Articles

Fake news and the pandemic of distrust

How to spot fake news