Jennifer Thomas

Our small urban school campus always had a room filled with books. Over the last 50 odd years, magazines and periodicals lay strewn on table tops, comic books and storybooks have lined cupboard racks and the coveted encyclopedias remained locked in glass cases. Could this be called a school library? Technically, yes. Like many other schools in India, our school too had a library that met government stipulations on paper. However, in practical terms, it remained a dead space that didn’t inspire much thought or action. According to official data, India has 15,07,708 schools of which 12,67,701 (84%) have a library. These figures should be heartening but unfortunately when we look more closely, we see that only 10,45,689 (69%) of these schools have a library with books in it (Unified District Information System for Education, 2019-20). If we were to take a step closer to examine what actually qualifies as a library, according to these statistics, the numbers will only look more bleak. The quality of books, the access students have to books, the nature of library activities, the status of librarians within the school community and the values which inform the library – all leave much to be desired. Our school library was no different. It did not thrive, it barely existed to meet a regulatory norm – the school must have a library. Why are school libraries dead?

Schools as institutions are guided and bound by legal and curricular frameworks mandated by the State. In a State controlled system, (education is a subject on the Concurrent List) it is often policy that determines legitimacy. Provisioning in schools, irrespective of the management (government, private, public-private), largely comes from policy documents even when it may or may not be aided by additional government funds and resources. In this article, we therefore turn towards the three national education policies (1968, 1986, 2020) to understand silences on libraries and also look at the Mudaliar Commission Report (1952), the All India Seminar on School Libraries Report (1962), the National Curriculum Framework 2005 (henceforth, NCF 2005) and the Right to Education Act, 2009 (henceforth, RtE, 2009) to understand the possibilities they hold for school libraries.

Despite the promise libraries hold, schools don’t invest in and nurture library spaces because education policy in the country doesn’t compel or hold school managements accountable for the same. Three years ago in 2018, we dared to reimagine our school library. This impetus to reimagine and transform our library mainly came from being a part of a community of library educators* who have a shared vision for libraries. Being a part of this cohort gave us the courage to build our library on constitutional values of democracy, inclusion and freedom of expression. The prevailing socio-political climate in the country further propelled us to re-examine our conception of the school library as a neutral space. It pushed us to think about our collection in the hope that the books in turn would push our readers to think more critically and empathetically about an increasingly polarized world that they were living in.

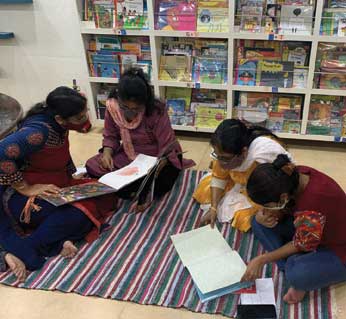

Through 2018-19, we tried to breathe new life into our school library by focusing on the values that would inform the library, the collection in the library and the space itself. We hoped the library would gradually come to be at the heart of the school as a safe space and that all library users would have open access to books. We had just completed one year of reopening the new library when the pandemic forced us to shut down. But by then our efforts had slowly begun to take root – serendipitously, during the pandemic even when the school remained shut, the school library gradually emerged as a bridge between the home and the school for many students. When lockdown restrictions eased in our city in late 2020, the first thing we did was to reopen the library for children to visit and borrow books. Children came, they browsed, they chatted with us, asked for recommendations, shared recommendations and promised to return. As library educators, our experience affirms that, in the shadow of a devastating global pandemic, the school library as a place, can become an important symbol of community, healing and sharing within schools.

This vision for the school library draws on ideas presented decades ago in the Mudaliar Commission Report of 1952 and the All India Seminar on school libraries, 1962 led by Dr. S.R. Ranganathan. The Mudaliar Commission Report of 1952, predates the education policy documents and intended to improve the quality of secondary school education in India. The report devotes an entire chapter to school libraries which is interestingly titled “The Place of the Library in Schools,” indicating that the library has an indispensable role to play in school education. The report took a holistic view of education and decried the examination culture, the poor status of general knowledge and students’ general disinterest in reading beyond textbooks. It recognized that the library could play a crucial role in improving the status of education in secondary school and for this it made recommendations in three key areas:

• The library as a place should be a centre of attention in the school. It should be colourful, decorated in collaboration with students and must be very attractive and appealing.

• The collection of books, journals and periodicals must be compelling. A committee of interested teachers (who are readers themselves) must be in charge of reading book reviews, visiting bookshops and selecting books. Students too can be invited to play a role in this. Teachers should have a pulse of what children like to read.

• The library should be conceptualized as a service within a school system, ably managed by a professionally qualified librarian who is on par with senior teachers in status and pay. The librarian would be in charge of offering library services school wide – key efforts including leading reading circles, giving publicity for books within the school and being available for consultation on selection of suitable books for different groups of readers.

Some other recommendations included enabling students to borrow books based on personal interest, keeping the library open on holidays and during vacations and even opening up the school library for the general public in the neighbourhood, in case there was no public library. We see hints of how the school library was imagined as a community space not just for the students but for any reader.

Many of these ideas were reiterated by Dr. S. R. Ranganathan in the 1962 report. The report re-emphasized issues of access to books, selection of books and staffing of school libraries. Open access to books was recommended and a student to book ratio of 1:20 was suggested. Most importantly, we see one of the earliest recommendations for including the library period in the school timetable for all classes. The document also highlighted progressive ideas on how library work could be made interesting and relevant for the learners through group work, project work, book displays and finding connections with subject curriculum through extension activities. If we were to pause and rewind to pre-pandemic times, what would we notice about school timetables and provisioning for the library period? What percentage of schools have library periods, what do librarians and children typically do in this time and what is the status of “library” as a subject against the dreary landscape of the exam-driven curriculum of Indian schools?

It is unfortunate that none of the suggestions of 1952 and ’62 found representation in the education policy documents of 1968 and 1986. While the policy of 1968 mentions ‘library’ once, (unfortunately only in the context of University education and access for these students), there is no mention of library/libraries in the policy of 1986. The silence on school libraries or other libraries, is an important one to note as it makes a statement about what was prioritized and what was not considered important and therefore excluded from the national vision for education. The expanded vision of a school library, first hinted at in the Mudaliar Commision Report, was reinforced in the NCF 2005 in these words,

“Both teachers and children need to be motivated and trained to use the library as a resource for learning, pleasure, and concentration. The school library should be conceptualized as an intellectual space where teachers, children and members of the community can expect to find the means to deepen their knowledge and imagination.” (pp. 91)

The NCF 2005 and RtE 2009 perhaps took us a few steps closer to imagining implementation. While the former gave suggestions for timetabling the library period and the different kinds of activities that can be done in this time, the amendment to RtE 2009 (21-A) made the provision of a library mandatory in every school. However, the NCF 2005 also added one more dimension to the library in talking about how school libraries should provide access to new information technology (IT/ICT) for teachers and students to connect with the wider world. The subsequent waves of advancements in technology however, have intermittently cast a shadow on the vision of school libraries, threatening to be more harmful than resourceful as it privileges access to information through IT, overshadowing more critical aspects of the library as a physical place, a safe space that fosters a community of readers and thinkers.

It is therefore laudable that the National Education Policy 2020 (henceforth, NEP 2020) mentions ‘libraries/library’ with purpose and intentionality 23 times. This is the most number of times libraries have been mentioned in any of the three national education policy documents since independence. This portends a renewal of the spirit of libraries within community spaces (across age groups) and an interest and investment in libraries to address social, educational and socio-emotional needs. The act of storytelling and book production too finds mention in the NEP 2020 and it emphasizes the place of stories and libraries across all classes and age groups. These are heartening inclusions. However, will it translate into more active and vibrant school libraries? Our limited experience in our school tells us that libraries come to life only when there is a librarian/library educator who tenaciously holds on to the idea of the library as a place and invites the school community (students and staff) to see the act of reading as essential for survival.

Schools are complex, social institutions which reflect and reproduce social hierarchies and it would therefore be impossible for the librarian to single handedly bring about systemic changes in how school libraries are conceptualized and perceived. While the school leadership too has a key role to play, historically we have seen that deep changes are set into motion over time, only when there is a stimulus in policy documents. Just as the NEP 2020 has led to a national mission on foundational literacy and numeracy, through the NIPUN Bharat document, we need stronger policy documents on libraries. There is an urgent need now more than ever to have a national policy on libraries and a subsequent mission on school libraries. This is our only hope for renewal of all the possibilities that the library as a place holds within a school.

*The school librarian participated in the Library Educator’s Course anchored by Bookworm, Goa in 2018

The author is an educator who works and teaches at Sharon English High School, Mumbai and is deeply invested in the idea of children reading and libraries thriving. She can be reached at jennifer.ktg@gmail.com.