Kaveri Dutt

I was first exposed to corporal punishment when I joined a boys’ school as a substitute teacher. It happened on the first day, when the class of 62 lively seven-year-olds decided to enjoy a self-declared holiday in the absence of their “regular” teacher. A colleague who was attempting to teach in the adjoining classroom, handed me a short stick with the kindly advice that the only way to discipline the boys was by wielding the rod! I was dumbfounded and momentarily confused as to whether I had taken employment in a hallowed seat of learning or in a concentration camp. I am, of course, happy to report that the stick stayed behind the door during my entire tenure in that institution, while I struggled, (thankfully with some degree of success), to devise ways and means of coping with my class of hyper-energetic, and occasionally intransigent, children without using any punitive measures that would cause bodily pain.

More than two decades have passed since this incident occurred, and I am shocked by the fact that a plethora of debates and discussions (including recommendation of stern laws against this primitive method of enforcing order), notwithstanding, corporal punishment continues to raise its ugly head from time to time in many institutions across the country. However, as a teacher, I roundly condemn this heinous act as it is cruel, borders on child abuse, and is detrimental to both the teacher who carries out the act and the hapless pupil who is the target of such punishment. Students who have been subjected to harsh, disciplinary practices are known to have subsequent problems with depression, fear, and anger. These students frequently lose interest in studies and show little interest in co-curricular activities.

More than two decades have passed since this incident occurred, and I am shocked by the fact that a plethora of debates and discussions (including recommendation of stern laws against this primitive method of enforcing order), notwithstanding, corporal punishment continues to raise its ugly head from time to time in many institutions across the country. However, as a teacher, I roundly condemn this heinous act as it is cruel, borders on child abuse, and is detrimental to both the teacher who carries out the act and the hapless pupil who is the target of such punishment. Students who have been subjected to harsh, disciplinary practices are known to have subsequent problems with depression, fear, and anger. These students frequently lose interest in studies and show little interest in co-curricular activities.

A report by the European Human Rights Committee, quoted in “Legal & Social Aspects of the Physical Punishment of Children,” published by the Commonwealth Department of Human Services, 1995, mentions that the infliction of physical punishment on children by adults, “is a morally repugnant, illegitimate and unjust assault upon another human being and especially reprehensible in that it is perpetrated upon those who are least able to defend themselves. A second argument is that physical punishment of children does not, as may be claimed, constitute an efficient and effective way of disciplining children in the interests of socializing and educating them; that it contributes to the development of aggressive personalities, and that other methods of control are more effective and humane.”

Is it about power?

The use of the term “control” in the passage quoted above is significant, for though corporal punishment is defined as the infliction of punishment upon the body with the intent to chastise and discipline, and refers to a wide spectrum of painful measures ranging from forced labour to mutilation, it is essentially a means of exercising control over another through the use of force and physical violence. Teachers, despite the easy availability of advanced studies on child behaviour, many a time, regard themselves as the law-makers of the classroom, where their authority, if challenged, may lead to awful consequences. These authoritarian figures with their erroneous views on class discipline firmly believe that it is imperative to retain the balance of power in their favour – if necessary, through the use of force. Roald Dahl’s caricature of a sadistic head of school who will brook no opposition to her authority, has many counterparts living in the real world!

To quote writer and teacher Bubla Basu, of Mumbai, “There is no reason whatsoever that can justify the use of corporal punishment in a classroom or a school. The point is not whether corporal punishment leaves none the worse for it, but whether anyone is really left the better for it, except the teacher or Principal who wants a “quick fix” to the situation. Corporal punishment, like any other, is about power. Power defies all reason and runs counter to any successful relationship. Violence is the last resort of the weak.

“It is a weak teacher who cannot build a relationship with a class, a weak Principal who uses the stick and not the carrot. These are the adults whom children may fear and resent even as they brag otherwise and then, in later years of class and school reunions ridicule or dismiss as ‘control freaks.’”

This has led to tragic repercussions and it is important to analyze the effects of corporal punishment on students, so that more do not emerge from the portals of their alma mater broken in mind and spirit. Corporal punishment, which was introduced in schools either as a deterrent or reform, has succeeded in neither purpose. A UNICEF report cites that there is a large body of international research detailing the negative outcomes of corporal punishment. Some of the conclusions are presented below:

Escalation: Mild punishments in infancy are so ineffective that they tend to escalate as the child grows older. The little smack thus becomes a spanking and then a beating.

Encouraging violence: Even a little slap carries the message that violence is the appropriate response to conflict or unwanted behaviour. Aggression breeds aggression. Children subjected to physical punishment have been shown to be more likely than others to be aggressive to siblings; to bully other children at school; to take part in aggressively anti-social behaviour in adolescence; to be violent to their spouses and their own children and to commit violent crimes.

National commissions on violence in America, Australia, Germany, South Africa, and the UK have recommended ending corporal punishment of children as an essential step towards reducing all violence in society.

Psychological damage: Corporal punishment can be emotionally harmful to children. Research especially indicts messages confusing love with pain, and anger with submission as the most psychologically harmful. “I punish you for your own sake. You must show remorse no matter how angry or humiliated you are.”

Corporal Punishment in schools is prohibited in nearly half of the world’s countries. In the past 20 years, eighteen countries have enacted laws prohibiting corporal punishment in all settings, namely in the home, in schools, alternative care and in the judicial system.

It is of interest to note that since the turn of the century, ten countries have officially prohibited all forms of corporal punishment. The pace of reform is gathering momentum in light of the UN Study on Violence against Children, which recommended in its final report, prohibition in law of all corporal punishment of children by 2009.

Many adults continue to argue that they were caned as children and are none the worse for it today. But talk to students and they will tell you not only about the physical hurt of being hit, but also the psychological effect caused by such humiliation – harsh words spoken in anger or derision have much the same effect as sticks and stones.

Proponents of corporal punishment favour it as it is an easy and temporarily effective method of instilling discipline, and nothing, they claim, works better than fear. They believe that to spare the rod is to spoil the child, and the slightest misdemeanour is swiftly and firmly dealt with by hitting the child. Children with ADHD, autism, and other behavioural disorders have suffered untold harm and their condition has worsened because of “stick” – happy adults.

However, while denouncing corporal punishment, I do not mean to belittle the need for discipline in schools, without which no proper learning and development can take place. Ms Nain, Principal, Birla High School for Boys, Kolkata, finds colour-coded cards a viable alternative. White cards are sent to parents for minor transgressions committed by their wards. If there is no change in the errant conduct of the pupil, they are handed green cards, followed by red ones, if the misdemeanour is a grave one. Three such cards would lead to expulsion from school. This system, Ms Nain opines, has led to an improvement in school discipline and provides the student ample scope to rectify and reform his deviant behaviour.

Ms Aarti Srivastav, educationist and teacher-trainer, New Delhi, has never been in favour of corporal punishment, meted out either in school or at home. She feels that the long-term solution to behavioural problems lies in helping the children develop an insight into their maladaptive patterns of behavior through moral reasoning. However, she is also of the opinion that mild corporal punishment is acceptable in extreme cases when a child demonstrates little emotional sensitivity and understanding of morality, despite repeated counselling sessions, and continues to indulge in behaviour that encroaches on the space of others. She stresses on the fact that this kind of negative reinforcement, even if it is applied when all other methods of positive behavioural support have failed, will at best only establish a lower, mechanical understanding of right and wrong.

Teachers’ concerns

Stringent laws leading to the arrest of several offenders from among the teaching community, public debates and awareness initiatives are all welcome measures that have helped in controlling the use of corporal punishment in schools today. I must mention, though, that the media hype and public outcry against teachers have led to a sense of panic and nervousness among many of them. Ms Amita Prasad, Middle School Co-ordinator, Modern High School for Girls, Kolkata, voiced the concern of many when she said that some teachers are afraid to instil any kind of discipline in the class, as they are afraid of the consequences. This would lead to a laissez-faire system prevailing in schools and certainly would not lead to the healthy growth of the child. Teachers too need reassurance, and training them in the rudiments of counselling would help restore in them a sense of self-worth. Schools that do not have counsellors and special educators on their rolls should devise a referral system so that students with behavioural disorders are provided with expert remedial help. Teachers too should be able to approach the school counsellors for guidance on personal and professional problems. An activity-based and interactive approach to learning that incorporates technological tools would also help in improving class-discipline by reducing boredom and passivity among the pupils.

In home spaces

It is common practice to place teachers under scrutiny, but homes are no strangers to corporal punishment. Many parents, either out of ignorance, their own limitations, stress, or unrealistic expectations of their children, often beat their children, thereby causing them untold harm. I still shudder at the memory of a student who dissolved into tears when I asked for an explanation of her constant misbehaviour, and showed me her back and arms that were criss-crossed with deep, purple welts and bruises caused by the frequent “belting” that she received from her father! Seminars and workshops suggesting ways of tackling behavioural problems in the young should be organized for parents too, to enable them to be more sensitive and understanding about the needs of their children. All stake-holders and caregivers in school and at home, need to collectively ensure that their wards grow in an environment of love, security and acceptance, where no Oliver Twist need be afraid to ask for more! Truly, in the words of Dorothy Law Nolte, it may be said that, “if a child lives with hostility he learns to condemn”, whereas “if a child lives with approval, he learns to like himself.”

The author is a teacher and has taught in several schools in Patna, Secunderabad and Kolkata. She also has some experience in school administration. She can be reached at dutt.kaveri@gmail.com.

Why punishment?

Divya Choudary

In early 2010, Rouvanjit Rawla, a 12-year-old student of the La Martiniere School for Boys in Kolkata, was humiliated and caned by the principal of his school. As a result of this, Rouvanjit committed suicide.

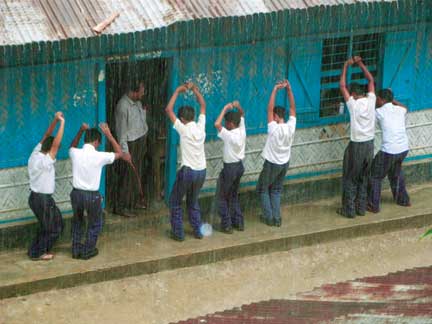

In 2009, Shanno Khan, a Class II student of MCD primary school, Delhi, was allegedly made to stand in the sun for two hours for not being able to recite the English alphabet. After slipping into a coma, Shanno eventually died.

In 2007, a teacher of the Central Railway English School in Jalgaon, Maharashtra was accused of giving electric shocks to students who were not paying attention in class.

Reasons often cited by teachers for resorting to punishment are stubbornness, telling lies, back-answering, questioning the teachers’ authority, not doing homework, being tardy, and not wearing clean uniforms or the appropriate ones. More serious reasons for punishment include hurting other students, bullying, stealing, and cheating.

So why is ‘corporal punishment’ favoured? Well, it brings quick results. Students, afraid of being humiliated or hurt, behave in the ‘required’ manner. The low teacher-student ratio, often witnessed in schools, makes it difficult for a teacher to give personal attention to each student and forces teachers to choose punishment as the method of disciplining them.

Principal of Unicent Child Centric School, Miyapur, Nalini Rao, says that it is important to locate the root cause of misbehaviour. Falling grades, disinterest in school work and tardiness may merely be symptoms. For instance, children’s acting out is usually a sign of unrest at home. While talking directly with the student usually helps, in more intractable situations, the school involves the parents, to ensure the child’s wellbeing.

In Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan Public School, Hyderabad, older students who act out are asked to fill in a ‘reflection sheet’, says Coordinator, Suvarni Rao. The purpose of the sheet is for the student and the teacher to understand the actions of the student, and the reasons and feelings behind these actions. For the younger children, issues like tardiness and unkempt appearances are dealt with by bringing them to the notice of their parents.

Given that the effects of corporal punishment are not just physical but psychological as well, one needs to analyse whether such punishment is constructive or even, necessary. Further, one may also question whether the teacher’s role should end at getting conventional results or extend to the facilitation of the child’s personal development. Finally, what remains fundamentally important is to find alternative ways to motivate and guide the children.

Nightmares during school days

Aarti Sethi

I sometimes wonder if Michel Foucault had gone to school in India if he would not have written his opus on punishment on the school rather than the prison. Anyone who has gone to school in India will tell you there is no institution that combines discipline and punishment in quite the same way as school. Everyone has tales to tell.

I went to military and central government schools for most of my life. I was lucky. The most I suffered was rulers on knuckles and palms, mild lashings on the back of the thighs and calves. But I was a girl. The boys got much worse. And my friends who went to Jesuit all-boys schools tell truly horrific tales. Of being made to roll into fetal balls on the floor to be kicked across the class by the chemistry teacher. Of being slammed on the back of the hands till blood flowed, of being made to stand in the sun in games period with no water till they fainted. Another friend, who is left-handed, had pencils placed between each finger, which the teachers would then twist in a macabre pedagogic ritual to ‘teach’ her to write with her right hand.

Some nights ago, a friend was recounting school day-nightmares. We commiserated and shook our heads knowingly. A friend who went to school in the West was horrified. We weren’t. None of it sounded strange. Everyone has stories like this. In every generation. If my father got a rupee for each time he was caned he would be a millionaire many times over. They differ in degree, not really in kind.

I never told my parents. I don’t know anyone who did. You didn’t tell your parents these things. You just dealt with it. You shrugged it off, it was a rite of passage. Children don’t tell, and for the most part, no one really cares. But then I was lucky. Many children are not. And on the rare occasions when the media wakes up, it is when a child dies. Or when children commit suicide. And it happens with chilling regularity. But the spectacular incidents are only visible extremes of a system of terror that is school. It becomes unacceptable when a child dies, or is seriously injured. But that children need to be disciplined with physical violence is not really a problem. There are no annals of the routine humiliation and psychic abuse that is vested on children every day.

I don’t mean to tar all teachers with the same brush. I am sure there are millions of dedicated gentle wonderful teachers who soldier on in a country which neither recognizes nor prizes nor praises a job which is low paid and comes with few perks. I know because I had the immense good fortune and privilege of being taught by many of them. But for every one light that glimmers on the horizon of that vast dark sea that is school, there are legions of individuals who can only be described as psychotic sadists who preside over classrooms in the manner of the chief wardens of torture chambers.

How else do you describe the teacher who hit 11 year-old Shanno Khan over the head and then made her stand in the sun for two hours with bricks on her back for failing to recite the English alphabet? Shanno died. Or the teacher who brutally beat Divya Pandey for not wearing the correct uniform? She died too. Or Ojaswi Khanna who lost hearing in his left ear because a teacher slapped him for forgetting to bring a compass to class*. And like everything in this country, going to school is deeply class inflected. If your parents can afford elite schools, chances are you will escape the worst of it. If your parents are poor and scraping together everything they earn to give their children an education, that child is rendered utterly defenseless in the most terrifying way.

School is, paradoxically, the only institution I can think of which naturalizes a complete asymmetry between transgression and punishment. The vast majority of sins which invite retribution in school would seem ludicrous in any other context. Talking in class, passing notes, not doing homework, failing a test, smoking in the bathroom, not paying attention during morning prayer, not wearing correct uniform, kissing a boy/girl, ‘back chat’, ‘talking back’, ‘acting smart’ – an endless list of minor ‘misdeeds’. Teachers punish children for ‘infringements’ of school discipline, and teachers punish children for their failure as teachers. Going to school in India is an exercise in abjectness – of being subject to absolute, totalitarian, untrammeled power, where the teacher enjoys complete unquestioned authority over you.

There has recently been much introspection in the public domain and media about the pressures of the board exams that claim the lives of thousands of children every year. Every one from Aamir Khan to Kapil Sibal has contributed their two bits on the travails of the educational system. And in response, the 10th class board exam has been scrapped, help lines have been set up, schools and parents are encouraged to seek the services of counsellors, etc. Much of this is, not surprisingly, a conversation restricted to elite schools. But nonetheless, a conversation about the terrors of the education system has begun. But what of the routinized violence that millions of children are subjected to everyday?

There is one thing though that school paradoxically achieves, despite itself. No one who goes to school harbours any illusions about the benevolence of institutions. Every cliche about power is true you learn – school teaches you that authority is hateful, that power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely, that the way to survive the system is to not invest in it, to not defer, to be suspicious, to be wary, to ‘kindly adjust’. It teaches you cruelty is infectious and to be on guard lest it take hold in you. It teaches you that hierarchy is real. It hopefully teaches you that since you know what it feels like to be terrified and abject and powerless, perhaps you are a little more alive to terror and abjectness and powerlessness in the world. You can of course learn other lessons – authority is alluring, proximity to power pays, cruelty is seductive. To which I look and say, ‘There, but for the grace of god, am I.’

If we really wish to raise a generation of fearless, independent young people who are not afraid to think for themselves and find solutions to the many ills that beset us, then the first thing we need to do is ensure that under no circumstances whatsoever is the body of a child made the foil for the insecurities and aggression of ‘teachers’. Corporal punishment institutionalizes hierarchy in the most intimate and terrible way – it legitimizes the oppression of the vulnerable, and justifies the sadism and megalomania of the powerful. It should have no place in our schools.

This piece was first published on www.kafila.org.

_______________________________________________________________________________________

*Both these incidents were reported in the press. See: Times of India, 18 April 2009, and The Tribune, 30 April 2011.

Aarti Sethi is a PhD student in anthropology at Columbia University, New York. She writes for kafila.org. She can be reached at aarti.sethi@gmail.com.