Chintan Girish Modi

My most difficult moments as a school teacher were those where I had to put rules before my own good sense. I am not alone in this, I have come to realize. Several teachers experience this predicament. It can be difficult for teachers to put their foot down in the face of institutional pressures. And this can bring not only agony but also an overwhelming sense of helplessness.

I recall a conversation with a teacher who shared, “I know this child in my class hates physics. Why are we forcing it on him? I’ve been speaking to my department head but she does not listen to me. Solving more worksheets every week isn’t going to make him start liking it. Why don’t we let him focus on the subjects he loves? It’s okay if he just passes in physics.”

In these words, I hear a dogged commitment to the child’s well-being. I also hear a plea for the teacher to feel recognized as someone who knows her children, their likes and dislikes, their talents and capabilities. In the managerial culture that is beginning to take over our schools, it is the teacher’s voice that often seems to be heard last, after everyone else has spoken – the director, principal, department head, subject head, consultant, counsellor, curriculum developer, and god-alone-knows-who-else. Sometimes, it’s not heard at all.

Another teacher expressed utter dismay at his school’s policy of getting students to come for revision classes during the examination week. “What’s the point of making them stay back in school for two hours after they have answered a three-hour paper? When I was a student, I used just go home and sleep, or play with my friends, or watch television. Gosh! Give them a break! Let them breathe, for heaven’s sake! If I had a choice, I would just go ring the bell right now,” he said.

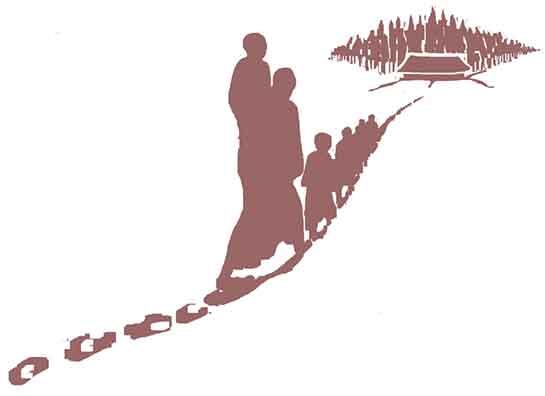

It can be painful to sit and watch your students dying to go home. The school’s policy clearly appears to originate from a line of reasoning that is not student-centric. How many schools in India allow teachers a safe space to question such policies and advocate in favour of the student? With more and more schools, especially in cities, being run like corporations, teachers are expected to be cogs in the well-oiled machinery of teaching hours, staff meetings, lesson plans, assessment rubrics, professional development, and never-ending paperwork.

When those who demand education reform identify the teacher as the one-point focus of what needs to be reformed, the scenario is frankly worrying. I wish we’d look deeply into what dehumanizes teachers and learn more about how to support them, instead of creating mechanisms to ‘professionalize’ the teacher-student relationship to such an extent where it becomes no different from a supervisor-employee relationship which revolves around submissions, deadlines, targets and objectives all determined by folks at the top.

This business-like work culture threatens to destroy a lot of what we cherish about the teacher-student relationship. It would be tragic to create school systems that do not allow teachers to love their students, and that compromise on the qualities of care, affection, and understanding we associate with our favourite teachers in school from the time we were children.

The heart, I feel, is extremely important in the teacher-student relationship. I am reassured of this as I read Daisaku Ikeda’s To The Youthful Pioneers of Soka: Lectures, Essays and Poems on Value-Creating Education. He writes about Tsunesaburo Makiguchi, a teacher and philosopher of education, who was imprisoned during World War II and died in prison.

Ikeda writes, “In the cold northern island of Hokkaido, where Mr Makiguchi lived before he moved to Tokyo in 1900, he would wash students’ chapped hands with warm water in winter to ease the pain. When snow storms raged outside, he would carry young students home on his back.” He adds, “For students who were too poor to bring packed lunches from home, Mr Makiguchi raised funds to provide meals and snacks. He would place the food in the caretaker’s room for the children to collect so they wouldn’t have to suffer unnecessary attention or humiliation.”

The author conducts workshops focused on creative writing and education for peace. He is the founder of People in Education and Friendships Across Borders: Aao Dosti Karein. He can be reached at chintan.backups@gmail.com.