Sushama Yermal

When we remark that a system of education has been doing badly, what exactly do we mean? What are the qualitative traits and quantitative measurements that can estimate the level of efficiency of education of an individual or an age group? Once we recognize what parameters to use and find out where the learning level stands, how can we use this information to improve the system? These are not remote, academic questions concerning only obscure scholars of research in education – they have been part of rather inarticulate worries in the everyday lives of ordinary citizens of India.

In spite of many large-scale drives like ‘learning without burden’ or the ‘sarva shikshan abhiyan’, schooling continues to be a chore without clear connection to the immediate experiences of children or their future as responsible, knowledgeable and productive adults. Employers recruiting for jobs that do not need much specialization also find that graduates out of high school or college are not equipped with the knowledge, skills and abilities expected for their age or learning.

The level of introspection among us Indians to find the cause and remedy the situation has not been sufficiently deep or satisfactory. Educationists elsewhere in the world have been genuinely worried and have tried both to understand the nature of the problem of education in India and to find solutions that can be immediately implemented. The book Rebirth of education by Lant Pritchett, Professor of the Practice of International Development at the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University, is a comprehensive effort in this direction. The book examines the root causes of the failure of systems of education in several developing countries, including India. What is more, it outlines the essential traits of a universally good system of education these countries can aspire to achieve, while also elaborating on the change in the mindset of the people and governments required to make this happen.

The premise from which the author looks at the problem is clear from his view on education, expressed in this paragraph: “Education prepares the young to be adults. The goal of basic education is to equip children with the skills, abilities, knowledge, cultural understandings, and values they will need to adequately participate in their society, their polity, and their economy. The true goals of parents, communities, and societies have always been education goals, and hence a multiplicity of learning goals. Schooling is just one of the many instruments in achieving an education.”

The book begins with establishing the enormity and gravity of the problem by explaining the evidence of poor learning outcomes in several developing countries. Data available about studies on school-age children in India, Pakistan, Ghana, Turkey, Mali, Bangladesh, Tanzania, Philippines, Colombia, Mexico, Brazil and other countries are cited and analyzed to glean the main traits that reveal the nature of poor learning outcomes in these systems of education.

Annual Status of Education Report (ASER), by the ASER Centre, New Delhi in collaboration with Pratham, a non-government organization, has been testing almost half a million Indian children every year since 2005 and the book laments about how the results show that things are getting worse. The percentage of grade five students who cannot read a story at the grade two level had been rising in the seven years preceding this book, till 2012. The fraction of students in grade five who cannot do division stayed the same or went up in the same period.

Pritchett’s background in developmental economics is at work when he compares the figures that quantify learning outcomes in developing countries with corresponding figures from developed countries. A large number of developed countries are members of the Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), and are therefore referred to as OECD countries. For any given age group (cohort) of children, learning outcomes look far better in OECD countries. From this comparison, he goes on to estimate the possible time required to attain cohort learning improvement in developing countries to reach levels similar to that in OECD countries. For instance, at the average pace of progress observed on the Educational Initiatives questions in India from grades four to six to eight, it would take 16 years of schooling to get 90 per cent of students producing correct responses on tests of rudimentary reading and arithmetic skills. At this rate, there is no scope of achieving even the minimum levels of learning by the time the students reach end-of-school age. “More generally, I show that at current learning profiles, even if the typical developing country achieved universal completion through grade nine, more than half of its students would not meet even a low international benchmark in learning. Unfortunately, while more schooling might be a necessary condition to achieving universal education, it is far from enough.”

Pritchett’s background in developmental economics is at work when he compares the figures that quantify learning outcomes in developing countries with corresponding figures from developed countries. A large number of developed countries are members of the Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), and are therefore referred to as OECD countries. For any given age group (cohort) of children, learning outcomes look far better in OECD countries. From this comparison, he goes on to estimate the possible time required to attain cohort learning improvement in developing countries to reach levels similar to that in OECD countries. For instance, at the average pace of progress observed on the Educational Initiatives questions in India from grades four to six to eight, it would take 16 years of schooling to get 90 per cent of students producing correct responses on tests of rudimentary reading and arithmetic skills. At this rate, there is no scope of achieving even the minimum levels of learning by the time the students reach end-of-school age. “More generally, I show that at current learning profiles, even if the typical developing country achieved universal completion through grade nine, more than half of its students would not meet even a low international benchmark in learning. Unfortunately, while more schooling might be a necessary condition to achieving universal education, it is far from enough.”

Even while citing evidence that facilities by themselves do not enhance learning, Pritchett tries to estimate the expenditure that may be required in terms of inputs for achieving better learning outcomes. The findings indicate that such efforts will only be wasteful. Also, quoting from the book, “Arguing about the causal impact of additional spending is pointless. The evidence suggests that the cost-effectiveness of spending, including the individual impact effects of various inputs, varies widely around the world.”

Pritchett emphatically points out the mistake of equating schooling with education. Expecting that if the child has attended school and the teachers have been supplied with required materials and facilities, appropriate educational outcomes are guaranteed is a familiar fallacy.

We see it in common experience that even sincere teachers are often forced to live double lives – knowing what is ideally required to be done versus what is expected of them due to the textbook-plus-exam culture. In addition to this, universal schooling goals suffer from high dropout rates and wrongly targeted incentives for attending school in case of children from socially disadvantaged sections. To quote an example from the book, “In January 2003, Kenya adopted a free primary education policy and abolished all fees in government-controlled primary schools, with the goal of increasing enrollments. Enrollments increased from 1997 to 2006, but nearly all of the net increase was in private schools, which did not eliminate fees. Moreover, the increase in the net enrollment rate in government primary schools, which eliminated user fees, was 0.4 percentage points, compared to 2.9 percentage points in government secondary schools, which did not eliminate user fees. One reading of this experience (Bold et al. 2011) is that the government’s attempt to make the schools cheaper in the interest of expanding enrollment and attainment caused parents to think that quality had gone down (as many of the fees were locally controlled and used for school inputs). This led to weak increased demand for government-controlled schools, while the relative price in money terms fell; and enrollment in government schools fell precipitously for the children of higher-educated parents.”

On the whole, the possible reasons for poor learning outcomes, applicable to most of the developing countries as listed by Pritchett are:

• unrealistic targets of achievement for age-wise cohorts

• ‘spider’ system of educational governance (described later)

• focus on facilities and salaries rather than outcomes

• wrong scaling decisions

• lack of systematized recognition of successful cases

Apart from these, in India we have an additional problem of inadequate teacher preparation. There are two kinds of extreme cases haunting this field – one where even untrained individuals hired on temporary contract seem to perform better in some places, another where even regularly employed, trained teachers fail badly at the same tests given to their students. Both situations argue very strongly for the immediate need for drastic steps to improve pre-service teacher education as well as teacher professional development in the country.

The reason why all the effort to provide “inputs”, i.e., the timely and adequate availability of facilities, personnel and materials does not seem to help in improving learning outcomes is quite simple: just ensuring the physical presence of all these does not automatically identify learning goals or monitor whether those goals are achieved. The fallacy of the system has been to assume that since learning is the purpose why schools have been established and children are enrolled, providing the inputs must trigger better results. Unless specific and sensible goals are set and their progress is followed up, we cannot expect the teaching-learning practices to improve. Until the habit of accountability is built in at every stage for all the individuals involved, no concrete outcome can be generated.

What appears to constitute the major difference in the performance of successful educational systems in producing outcomes is the effectiveness with which people in those systems – students, teachers, administrators, parents – use resources. Appearances can be forced from outside, but performance is driven from within. Pritchett notes that no developing country has an evidence-based plan for achieving significant progress in education. “Nearly all countries have plans to spend more on inputs and will call that “quality,” but none has a plan for increasing student capabilities. First, very few countries have any articulated and measurable goals – that is, clear statements of the magnitude of the improvement in learning objectives that will be achieved by its plans for input expansion. Rather, nearly all plans are circular: quality will be improved when inputs are expanded because inputs are quality. Second, no country has a plan that links plans for input expansion to learning objectives based on any evidence about effect sizes. While learning objectives may be mentioned, their magnitudes are not quantified.”

Merely imitating the current practices of countries where education is doing well won’t do to improve the system in countries that are doing badly. Pritchett explains the thoughts behind this conclusion in the section he calls “Why West does not know best”. He observes that the learning profiles of children in OECD countries have been doing quite well from the 1950s onwards and more interestingly, have almost stagnated at a good state of performance for the last two or three decades. Therefore, comparing the current trends in these countries with those of developing countries does not make any sense because the system of education in OECD countries is not dealing with the same problems as developing countries at all! Even the elderly Western educationists of today were born AFTER the learning profiles started doing well, and therefore have no personal experience of how to improve the profiles in the first place. They might not have been old enough even to watch and understand how the process progressed at that time. This basically leaves it to the educationists in the developing countries to try and come up with their own solutions to the failures of their respective systems of education.

So, where does this leave us regarding the rebirth of education, if we are unaware of a handy plan to repair the system? The central thesis of the book is to precisely locate the differences between successful education systems and those which are performing badly – Pritchett describes the difference by equating it to the difference between the lifestyles of two distinct kinds of animals, by following the classification made by Ori Brafman and Rod Beckstrom (2006) who see decentralized organizations as starfish and the centralized ones as spiders. Quoting from Pritchett, “They adopt the metaphor of a spider because a spider uses its web to expand its reach, but all information created by the vibrations of the web must be processed, decisions made, and actions taken by one spider brain at the center of the web. The starfish, in contrast, is a very different kind of organism. The starfish is a radically decentralized organism with only a loosely connected nervous system. The starfish moves not because the brain processes information and decides to move but because the local actions of its loosely connected parts add up to movement.”

When the public schooling systems work in the fashion of spider organizations, and learning outcomes are not good, the root of the problem remains intractable due to the top-down manner in which the system functions. To overcome this, Pritchett recommends evolving starfish type of organizations where each independent unit is free to function uniquely, its effectiveness is objectively evaluated, resulting in only successful units being allowed to continue or scale up. In practice, this calls for a strategy similar to evolution of life forms: many types of schools run by different ‘proprietors’ are allowed to function simultaneously; their effectiveness is assessed thoroughly and the results made public; students/parents/guardians are given a flexible choice to move between schools; objective criteria are set for eliminating badly performing schools that fail to attract reasonable number of students; successful schools are analyzed to understand their qualities and suitable types are scaled up. This strategy stands to reason, but it is also important to realize why such a simple mechanism has not been operating in reality, as explained below.

Pritchett reminds us of the historical reason why most governments adopt centralized systems of education, which no longer needs to be that way in modern societies: when nations in the contemporary sense of the term came into being, governments needed to shape the ideology of the upcoming generation of citizens. Hence, it was useful, nay necessary, to make public schooling unified and uniform. As inculcation of beliefs cannot be contracted to a third party, the governments had to keep a centralized hold on the system of education. Pritchett touches upon the different types of origin and spread of public schooling in several countries – Japan, Netherlands, Belgium, France and Turkey.

In spider type of organizations, centralized and badly functioning system of education has resulted in ‘value subtracting and rent-extracting’ schools that do more harm in terms of both wasting resources and not delivering any learning to students. Such systems have another dangerous trait: that of concealing their defects by superficially managing to mimic better systems. This camouflage results in the loss of accountability at all stages, held in place by rigid hierarchical structures.

To help in building the framework of moving from ‘spider’ systems to ‘starfish’ systems, Pritchett identifies six traits of an effective starfish ecosystem, as listed below. In the context of education, if the system of education either already displays or strives to acquire these traits, it can hope to do really well in terms of educating students.

- Open: How is the entry and exit of providers of schooling structured?

- Locally operated: Do those who manage schools and teach in schools (and the local coalitions of parents and citizens they are accountable to) have autonomy over how their school is operated?

- Performance pressured: Are there clear, measured, achievable outcome metrics against which the performance of schools can be assessed?

- Professionally networked: Do teachers feel a common professional ethos and linkages among themselves as professional educators?

- Technically supported: Are the schools, principals, and teachers given access to the technical support they need to expand their own capacities?

- Flexibly financed: Can resources flow naturally (without top-down decision-making) into those schools and activities within schools that have proved to be effective?

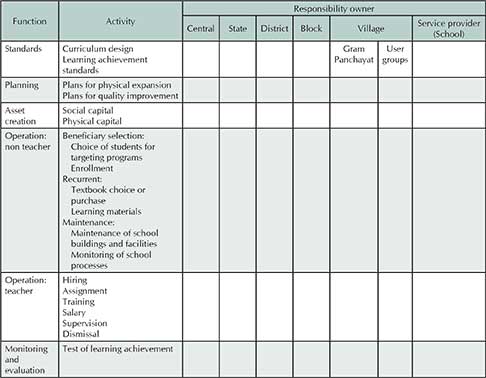

Another set of criteria that differentiate starfish systems from spider systems is the way in which responsibilities are allocated, as listed in the table below. It is worth mulling over what the current distribution of functions in the following table is in the Indian system of education and what we would like it to be in the near future.

Pritchett narrates the examples of three successful, yet unique systems of education to inspire the efforts of developing countries: Western (mainly American) higher education, the International Buccalaureate schools and recent developments in education in Brazil.

From the discussions in the book two concepts radically different from the current system of education in India emerge, which may help to alleviate many problems being faced by the system at present. These are, (a) evidence-based decision-making to identify best practices and successful schools (b) space for and evaluation of disruptive innovation. Given that a new National Policy of Education is being formulated at the moment, we can hope that these pragmatic yet costless measures are incorporated into the system and their proper implementation gives us the desired improvement in education.

References

- https://www.cgdev.org/publication/9781933286778-rebirth-education-schooling-aint-learning

- www.asercentre.org

- Bold, Tessa, Mwangi Kimenyi, Germano Mwabu, and Justin Sandefur. 2011. “Does Abolishing School Fees Reduce School Quality? Evidence from Kenya.” CSAE Working Paper WPS/2011-04. Centre for the Study of African Economies, Oxford University.

The author has been a researcher in biology and an educator, taught at the undergraduate programme of IISc from its beginning; now freelancing as an independent advisor to academic institutes and teaching faculty. She can be reached at ysushama@gmail.com.