Jennifer Thomas

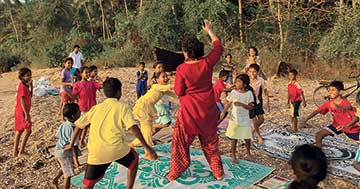

Cacra is a small sea-side village located near the Goa university campus on the Taleigao Plateau in Goa. Traditionally, it has been a tribal community of fishing families. The children go to the local government school by the day and some of them attend tuitions in the evening. Most of them are first generation school goers with limited access to a print-rich environment at home. Life proceeds quite normally on most days for these kids, except on Tuesdays, when Bookworm’s red van comes along carrying a magical world of stories and storytellers.

Cacra is a small sea-side village located near the Goa university campus on the Taleigao Plateau in Goa. Traditionally, it has been a tribal community of fishing families. The children go to the local government school by the day and some of them attend tuitions in the evening. Most of them are first generation school goers with limited access to a print-rich environment at home. Life proceeds quite normally on most days for these kids, except on Tuesdays, when Bookworm’s red van comes along carrying a magical world of stories and storytellers.

Bookworm is a Goa-based Not for Profit Company co-founded by two educators, Sujata Noronha and Elaine Mendonsa. It began in 2006, as a small lending library that initially operated out of a family-owned second floor apartment at St. Inez, Panjim. Stocked mainly with books (around 750 to start with) that Sujata and Elaine’s children had grown up reading, the idea was to create an innovative space for literacy to enable children to fall in love with books.

By 2008, income flow from the better-off families who accessed the library, now stocked with over 15000 books, motivated Elaine and Sujata to take their literacy initiative to disadvantaged families through ‘The School Book Treasury’ (SBT) program. Under this program Bookworm enriched government school classrooms with storybooks and storytelling sessions with support and training for teachers to conduct library sessions. Today SBT works with 22 schools across the state. However, the innovative duo did not stop at that. It was in 2009, after a mammoth fund raising drive that Bookworm invested in its most utilitarian asset – the red van. The red van, now synonymous with Bookworm ushered in a new phase for the home-grown organization. The red van made books and Bookworm, more accessible than ever before to people around Goa. It also made Bookworm more ‘mobile’ than it had ever been. By 2011, Bookworm added another program to its bouquet of literacy interventions, ‘The Mobile Outreach Program’ or popularly known as MOP.

Through the MOP, Bookworm takes books and an innovative library program, to six demographically and socio-linguistically diverse pockets in Goa. These children come from some of the poorest socio-economic groups in Goa and until now had no access to books or opportunity for creative work. For Megha, who works on the MOP team, “The aim of the MOP is to create a learning environment that these children haven’t experienced before, at school, at home, in society. Literacy, the ability to read and write comes after. But the primary aim is to make them feel the love and the essence of each children’s book.” Niju, who heads the MOP initiative adds, “While we want to ensure easy access to books for children, we also make sure that our intervention is rooted in a sound pedagogic understanding of literacy. We want our sessions to be useful and we want to ensure children are impacted in a positive way.”

A typical MOP session always begins with what Sujata calls, certain ‘non-negotiables’. Formal greetings in English like ‘Good evening!’ ‘How are you?’ ‘I am fine,’ set the tone for every session. This is followed by singing a few songs, some in Hindi or Konkani and some in English. A read-aloud is a feature at every site. This is preceded by a round of fun pre-reading activities that set the scene for the story at hand. Following a short discussion after the read-aloud, every child does a post-reading activity that integrates creativity with literacy.

A typical MOP session always begins with what Sujata calls, certain ‘non-negotiables’. Formal greetings in English like ‘Good evening!’ ‘How are you?’ ‘I am fine,’ set the tone for every session. This is followed by singing a few songs, some in Hindi or Konkani and some in English. A read-aloud is a feature at every site. This is preceded by a round of fun pre-reading activities that set the scene for the story at hand. Following a short discussion after the read-aloud, every child does a post-reading activity that integrates creativity with literacy.

The language used for discussion varies, depending on the site. The Indiranagar basti in Chimbel has a migrant community. Though Marathi is not their home language, they attend a Marathi medium government school in Chimbel. Taleigao and Merces market site too have a multilingual migrant population of children in the age group of 4-14 years. Hindi is the preferred language at these sites. Cacra and Chicalim are two sites with a local tribal population. There is an obvious schism in languages used in schools, homes, and neighbourhoods. This adversely impacts children’s learning levels at most sites except Cacra. Sujata explains, “At Cacra, the linguistic profile of the group is Konkani, they go to a Konkani medium school and this must help their language comprehension. We know that having a strong foundation in your own language allows you to acquire ‘other’ languages. We see that at the Cacra site and can compare it across the multilingual sites we work with, recognizing how significant this factor is.” Keeping the multilingual profile of its audience in mind, Bookworm uses story books not only in English, but also in Hindi and Marathi for the library program.

One special site that MOP works with is the National Association for the Blind (NAB) center at Santa Cruz. Sujata and Elaine observe that the children here are extremely keen listeners who follow the cadences of a story with good concentration. Hence, choosing a slightly lengthy story for this group isn’t a bad idea. Sujata remembers the time they read, The Mountain that loved the bird, a story that is rich in textual imagery. Sujata reflects, “A read-aloud of this length is possible because the children at this site, have very good auditory memory, auditory comprehension is heightened as they have to rely on that sense rather than the visual and we learn every time how to design our sessions based on the children.” Recently Bookworm has managed to procure a wonderful set of Braille storybooks for the students at NAB.

Reading at MOP is not about identifying A or B or about pronouncing words correctly. It is rather about immersing yourself in a story and then making meaning of the world around. Like Azhaar at Chimbel, who told Sujata, “Teacher, you remind me of a book,” when she wore a sari. He was referring to Tulika’s My Mother’s Sari, which they had read a few weeks ago. It’s heartening to see how carefully books are selected for each site keeping in mind the learner, learner levels and their social contexts! Strategies like pre-reading activities, introducing key vocabulary and employing prediction techniques reflect sound pedagogic understanding that Bookworm’s library program is grounded in. The multisensory nature of each session with many games and activities perhaps also explains why children remain focused and riveted through the one and half hour session. Without prescribed primers or strict reading rules, the program is unstructured, and yet that seems to be its strength. Bookworm’s approach to reading doesn’t seem to be didactic or mechanical, but organic.

Reading at MOP is not about identifying A or B or about pronouncing words correctly. It is rather about immersing yourself in a story and then making meaning of the world around. Like Azhaar at Chimbel, who told Sujata, “Teacher, you remind me of a book,” when she wore a sari. He was referring to Tulika’s My Mother’s Sari, which they had read a few weeks ago. It’s heartening to see how carefully books are selected for each site keeping in mind the learner, learner levels and their social contexts! Strategies like pre-reading activities, introducing key vocabulary and employing prediction techniques reflect sound pedagogic understanding that Bookworm’s library program is grounded in. The multisensory nature of each session with many games and activities perhaps also explains why children remain focused and riveted through the one and half hour session. Without prescribed primers or strict reading rules, the program is unstructured, and yet that seems to be its strength. Bookworm’s approach to reading doesn’t seem to be didactic or mechanical, but organic.

Though Bookworm is clear that theirs is not a ‘literacy’ program but a ‘literature’ program, one can’t help but wonder if the latter can be successful if children don’t have basic literacy to read. In a country where surveys only highlight abysmal reading comprehension levels, the challenge for the team may be to define objective indicators which show that the children are reading and their reading levels are improving. There are subtle indicators visible on the field that show a change in children’s attitude to reading; they remember book titles, they select books for book issue with a discerning eye, they listen to story narration with interest. This could be just the tip of the iceberg. Bookworm’s ultimate impact in terms of improvement in reading levels in a particular language remains to be gauged.

What is remarkable however is, that children’s literature which has always been the resource of a few, with a program like MOP, is making its way through storytellers and readers to many. For now Bookworm is busy battling ground-level challenges of finding space, volunteers, and resources to keep the program going with the same passion and zeal that its founders began the program with.

The author works as a teacher educator and leads the Language Department at Muktangan, Mumbai. She’s currently also on a fellowship with the Sir Ratan Tata Trust to develop a Resource Book for story-telling. She can be reached at jennifer.ktg@gmail.com.