Chintan Girish Modi

In most conceptions of school and places of organized learning, a library is central. In India, where many schools lack even a blackboard (or a teacher!), a library of any description is perhaps considered a luxury. Even in schools where libraries exist, they take many forms and are bound by rules and regulations that constrain use.

In most conceptions of school and places of organized learning, a library is central. In India, where many schools lack even a blackboard (or a teacher!), a library of any description is perhaps considered a luxury. Even in schools where libraries exist, they take many forms and are bound by rules and regulations that constrain use.

This issue of Teacher Plus looks at just some of the many kinds of libraries that children, teachers, and communities have access to, in schools and out, fi xed and mobile, formal and informal, and considers ways in which we can extend the idea of the library and its many uses.

My dream is to start a library for children. The shelves are over-flowing with books, and each time I pick up a new set, there is a struggle to make space for new friends that come from bookshops and discount sales, from pavements and publishing houses. I wish to create a space where children can fall in love with the magic of stories, wander off into exciting worlds, and begin their journey to learn about themselves and others. The urge to make this happen becomes more intense each time I hear about unimaginative attempts at encouraging reading. There is enough reason to believe that those who take it upon themselves to ‘instill the reading habit’ often end up doing much harm to the children whose cause they claim to espouse.

Anmol Kapur is a Class 5 student of Delhi Public School in Hyderabad. He represents the classic case of a book lover who cannot read what he wants to because of adult notions about what is appropriate and what isn’t. He says, “In the school library, there are so many rules. They don’t allow you to read what you like. They tell you that you can’t read Hardy Boys before Class 5 because you won’t be able to understand it.” Grusha Prasad, a Class 8 student from Rosary Convent High School in Hyderabad, has a similar complaint. “The people in our school library are very protective about the books they give out. All the students get books based on the class they belong to. Sometimes, they limit it to Enid Blyton. It is just one room, and all the books are in a cupboard that we cannot touch without permission.”

It is worth investigating why school libraries are the way they are, particularly the issue of not allowing kids free access. Shravya, a student of Class 10 in Aurobindo International School, says that till Class 7 it is the class teacher who decides what the students will read. “This is because children from younger classes otherwise end up reading more about cinema or cricket. The class teacher advises the library teacher about the books to be given for kids to read. After Class 7, we are allowed to choose our own books.”

At one level, one tends to think that teachers are justified in regulating the choice of books since they have the ‘good’ of the children at heart. However, it is vital to ask what this ‘good’ is. Different people will come up with different definitions of this ‘good’. Some teachers may not allow children to read books which are considered unsuitable for their age group. Other teachers may place restrictions on reading story books. The library is certainly a valuable resource centre for children seeking help with projects and assignments, but it is unfair to restrict children’s reading only to reference books. It is important that they be given the freedom to just look around the library and explore for themselves.

Perhaps another reason why school librarians are wary of allowing free access is the fear that children might damage the books. The fear has its own justification. Some of the books are expensive, and hence difficult to replace. Despite this, one finds books with pages torn out of them. Pencil marks, scribbles and food stains aren’t rare either. However, using this as a reason not to allow children to read what they find interesting is perhaps not the best way to handle this situation. A more effective way of ensuring that books are kept in good condition is to promote a culture of caring for books. When this happens, students will treat their books with respect and responsibility.

Schools usually allot a library period for each class, during which a teacher accompanies the students to the library. The number of library periods per week differs from one school timetable to another. Aurobindo International School in Hyderabad and Secunderabad Public School allot one library period per class per week. Orchids International School has two periods a week for students up to Class 5, and one library period per week for students from Classes 6 to 10. The school encourages students to use the library during lunchtime and free periods. If the library is occupied by a class at any point, there are separate seats for extra people to sit aside and read.

Oorvi, a Class 12 student of Nasr School for Girls a high school in Hyderabad, mentions that while they do not have a class library period, they are allowed to visit the library at any time and borrow the books that they require. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan Vidyashram at Jubilee Hills, Hyderabad, takes the library period idea a step further. A. Sita, Librarian (Classes 6-10) says that students are allotted a library period, but can walk in anytime during school hours. She emphasizes the need to encourage children to explore the world of books rather than merely imposing on them a routine of reading.

Then there are schools which do not allow their students to step into the library. The teacher brings the books to class during the library period, and each student is handed out a book for a stipulated period of time. Gayathri Rao, librarian of Secunderabad Public School tells us that for younger kids, the class teacher requests a list of books that they require, and these books are sent to the classroom. “Children from Class 6 onwards visit the library. They browse through the books, which are arranged by subject matter and pertinent class,” she says. Children who are limited by such restrictions miss out on the opportunity to develop an intimate relationship with books at an early age.

It is only fair to acknowledge that many schools libraries do make the effort to promote themselves as vibrant, welcoming spaces. The National Book Week organized by Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan Vidyashram is one of the greatest attractions at their library. Being held since the last 10 years, it comprises events such as essay writing, jacket designing, complete-the-story competitions, debates, elocutions, book readings and talks by well-known authors. In the past, they have had Anant Pai, Mythili Nair and Cheryl Rao as guests.

At other schools, children participate in activities such as making bookmarks, creative writing and publishing their school paper. Esther, who teaches Class 3 students in a Hyderabad school, organizes Inquiry Points with the help of the school library. During these sessions, children can ask questions based on their syllabus. The librarian accordingly sets aside the books relevant to the particular topic. At other school libraries, activities like book reviews and book analysis start from Class 4 or 5 onwards.

Writing a review can be a rewarding exercise for children. It will urge them to think about what they have read, reflect on their own reactions, and then form judgments. Reading is to be encouraged not only for the pleasure it can offer, but also for the opportunity to learn about different people and cultures, and ways of thinking and living and being. It would be tragic if the child were expected to write a review just in order to prove to the teacher or librarian that he/she has ‘really’ read the book. Such practices defeat the very purpose of a library. Activities to encourage reading must be carried out intelligently and sensitively.

Though the significance of school libraries cannot be discounted, one has to admit that they do fail at times on certain counts – restrictions on the choice of books borrowed, time constraints posed by school timetables that can allot only a limited window of time for library periods, undue emphasis on reading books that supplement the syllabus, among other reasons. It is in this context that out-of-school children’s libraries become crucial.

Radhika Kundalia runs such a library in Mumbai, called Akshara. Along with busts of Buddha and Ganesha that bring serenity, there are paintings by kids to enliven the place. Here, the usual fiction favorites share space with child-friendly editions on Freud, Jung, Shakespeare and Nietzsche besides books about ‘the birds and the bees’. Yoga sessions, writing workshops and art events are also held in the library premises. In addition, there is a general section on parenting and a special one for parents of children with autism.

Radhika says that a lot of children today are not interested in reading because we have taken the fun out of it. However, when they see other children reading, they want to try it out for themselves, and sometimes they get hooked. She observes, “Sometimes parents have very rigid ideas about what their children must read. Some want their kids to read Enid Blyton because the language is good. Others don’t want their children reading American books. And there are some who are happy only if their children pick up abridged versions of classics. I tell the parents not to force their children to read a particular author. Even if a child reads a comic, it’s okay.” She does not try to decide for the children what they should read. This is commendable, because though Children’s Literature is writing meant to engage children, it is often adults who dictate what is to be read by the child – be it a parent, a teacher or a librarian.

Another library that is becoming popular with kids is housed at Kaleidoscope in Hyderabad. Kaleidoscope is a learning centre that offers a mix of structured, semi-structured and unstructured learning programs and after-school activities aimed at making learning a joyful and stress-free experience. Children can opt for the library services independently and also in combination with other programs where they come in right after school, wash up, have a snack and get to play games, learn music or work with educational software.

Anmol, who is known for picking up books usually read by older kids, is happy to be here. Omana Hirantara, who runs Kaleidoscope, tells us that Anmol devours books. There are books that he has read more than a dozen times. He also enjoys video games. He says, “I don’t know what I like about books. I just find them very interesting, and I’m attracted to them. If you give me a choice between a book and a video game, I would pick the book.”

Radhika and Omana put up paintings done by children in their libraries. These do not emerge out of competitions. Every child is entitled to having her work displayed. Says Omana, “In school, there is always a pressure to perform. There are marks for everything you do. At Kaleidoscope, we want to celebrate creativity in a non-competitive atmosphere.” Adds Radhika, “If we made it competitive, children wouldn’t enjoy making the painting, but be worried about whether it’s good enough to be put up or not.”

The success of libraries like Akshara and Kaleidoscope perhaps lies in the freedom that they offer children. They recognize that different children have different preferences, and it is therefore important to make available a wide range of books. They do not insist that the children read a particular author or genre of writing. When children are exposed to a variety of books, they will have the opportunity to experiment with something that they are not familiar with. They also support interests other than reading.

Libraries ought to be spaces that nurture young minds. As J. Krishnamurti would attest, this nurturing can happen only in an atmosphere of freedom. If school libraries reorient themselves to this understanding, with the promise of offering a mix of learning and fun, children will embrace them with delight.

Caring for books

- Take students on a ‘tour’ through the library. Show them the different sections into which books are classified.

- Introduce them to people who help run the library and the kind of jobs they do.

- Initiate them into the different aspects of running a library. Show them book catalogues sent by publishers.

- Take them to a book fair. Show them how new books are bound and catalogued. Involve them in mending torn books. If this is not possible, have the kids just come and take a look.

- Distribute bookmarks with bright pictures or funny lines. You could also hold a book-mark making workshop. Ask the art or craft teacher for help.

Dos and Don’ts for Libraries

Do

Do

- Expose the child to a wide range of books.

- Encourage the child to talk about her likes and dislikes.

- Suggest books based on the child’s interests.

- Allow the child to explore books classified for other age groups.

- Develop the library as a place that offers a refuge from the classroom.

- Offer a bright atmosphere and comfortable seating space. Mats and cushions are good options.

- Let the child touch and feel the texture of books. Let her hold and hug and smell them and put them on her lap.

Don’t

Listen to Pulu

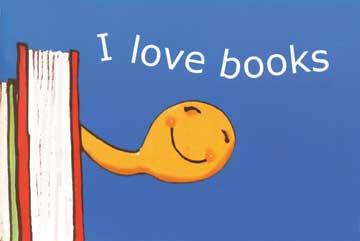

Here’s a useful aid for parents, teachers and librarians trying to introduce kids to the fascinating world of books. Thankfully, it does not throw up a list of mustreads, but helps children to “just look at books – to think and talk about them.” I love books is written in a friendly manner, with Pulu the bookworm as a guide who acquaints his reader friends with different aspects of books – author, illustrator, publisher, favourite characters, new words and favourite lines.

Here’s a useful aid for parents, teachers and librarians trying to introduce kids to the fascinating world of books. Thankfully, it does not throw up a list of mustreads, but helps children to “just look at books – to think and talk about them.” I love books is written in a friendly manner, with Pulu the bookworm as a guide who acquaints his reader friends with different aspects of books – author, illustrator, publisher, favourite characters, new words and favourite lines.

It enables kids to develop a basic vocabulary to describe their favourite books, and places and families they meet in books. It helps them review books and rate them on a 10-point scale, and also prompts them to think up alternative endings for their favourite storybooks. It is well illustrated and contains a number of stickers that children can use to express what they feel about the books they have read. The book is aimed at Classes 1 to 5.

The author is an M.Phil student at The English and Foreign Languages University, Hyderabad. Apart from education, his interests include poetry, travel and children’s literature. He can be reached at chintangirishmodi@gmail.com.

Related articles

Meet learn and enjoy

Oasis for book lovers

‘Driving’ knowledge