Kamakshi Balasubramanian

Humour not only provides welcome distraction from routine, it does more. Research has demonstrated that when purposefully integrated into the teaching and learning process, humour can

- better engage the learner’s attention;

- enliven sagging spirits when topics or aspects of a lesson are inherently difficult to absorb or are too abstract; and

- increase teacher accessibility to students where necessary.

The teaching and learning process includes the use of textbooks, teaching materials, assignments, field trips, and the like. When is it useful to employ humour in this process? During scheduled lessons, teachers use many techniques through which they deliver the curriculum, and not all of these techniques necessarily benefit from or even require the inclusion of humour. Generally, the nature and purpose of activities would determine whether the use of humour is appropriate: for example, tests and examinations generally preclude the introduction of elements, including humour, which could distract the student. Sometimes, the theme or topic would determine whether humour is appropriate: for example, if the lesson is on a socio-ethical issue such as capital punishment, it is difficult to include humour. This does not mean that serious or weighty matters cannot be treated with humour; profound matters require subtle and sophisticated humour, the type over which only the Mark Twains of this world have mastery. So, weighty matters are best treated in the classroom with measured seriousness.

Many researchers in education have written about how a responsible teacher could use humour to enhance the classroom learning experience of students. I am, however, going to shift attention to another aspect of a teacher’s role in creating opportunities for expression and appreciation of humour in the classroom. To create humour means to introduce a comic perspective or light-hearted approach into a situation or phenomenon and generate amusement. Rather than present the teacher as the provider of appropriate humour, I propose to show how a teacher can actively encourage students to create wholesome and purposeful humour. I am going to focus on the ways in which humour can be incorporated in the day-to-day practices of classroom activities within the duration of a scheduled lesson, when both teacher and learners are engaged in “face time” interaction. We shall not discuss here the use of humour in teaching materials and in extracurricular activities.

One simple way is to use games to help students organize information. Such things as spelling and arithmetic lend themselves to the use of games that generate spontaneous humour. Have you played Hangman or Pictionary in a classroom, just using the black (or white) board? As little as 15 minutes a week to revise spelling or work on vocabulary items in a language class through a game changes the level of student receptivity more than one would assume.

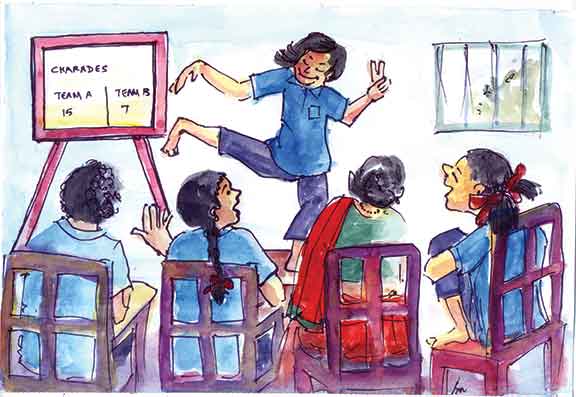

The popular parlor game of Charades (also called “Dumb Charades”) is very handy to help students internalize definitions. Let us see how this might work, for example, to understand the meanings of literary terms. The players are told that only literary terms and closely related concepts are to be acted out, and the fun begins when teams easily score points for correctly guessing “tragedy” and “comedy”. The contest heats up as terms such as “irony” and “soliloquy” enter the game. The mime depiction of these concepts inevitably arouses much laughter. It is not as if only language classes can use word games. If I were to be a chemistry teacher, students would play Pictionary to learn terms such as “evaporation” and “catalyst”. In the environment science class, Charades would work to mime various phenomena – for example “greenhouse gases” or “noise pollution,” to name just two.

The point is that when students play a game that is naturally comical, the humour generated is spontaneous and wholly participatory. Mirth and amusement are the creative result of active student engagement, and when a game is played, everyone’s attention is concentrated on the process. As students get used to such short interludes of simple parlour games, they get more inventive and creative.

Twenty Questions, which I usually redesigned as Ten Questions, served very well in history and geography classes. If you were “It”, you went out of the classroom while the rest of the players gave you an identity. Say, in an Indian history class, you were “It” and you had to guess that you were Sarojini Naidu. You would have 10 opportunities to ask questions that required a “yes” or “no” to arrive at the right answer. Learning the features of geographical regions can be fun when students play this same game. The person who is “It” has to ask 10 questions to discover, for example, which geographical region he/she belongs to. I found that it was essential to use a timer or set a time limit when playing an elaborate game, such as this one.

Very short skits performed by groups of students to explain a concept or raise awareness often showed that participants have an inherent ability to infuse the comic element in unexpected ways – visually, verbally, and sometimes through movement. Because actors intuitively understand that comedy holds audience attention, and perhaps because students find many things funny (things that teachers are too busy to notice), skits and role play offer abundant opportunity for humorous takes on things being learned.

Verbal and group activities, some of which I have described in the foregoing section, create opportunities for generating humour, with the added benefit of nurturing habits of team work.

Individual work can also offer students avenues for learning through the use of humour. Writing assignments about events in history, processes in the sciences, or even applications in mathematics, open up the potential to introduce humour more than one might believe. In a biology class, for example, students could be asked to write a short “journal entry” by a freshly hatched chick of its story from conception. A detective story about why an experiment on electrical circuitry in the physics lab repeatedly goes wrong would help the learner to understand the steps involved in successfully performing that particular experiment. In language and literature classes, the opportunities are vast for this kind of work. In classes I have taught, students have composed limericks to describe literary characters and written alternative endings to famous sayings and quotations.

Creating humour is a useful exercise. Accessing available humour is just as useful. Using the Internet and library resources, students have looked for and found genuinely humorous cartoon depictions of topics being learned in a variety of disciplines, from history to higher mathematics. With the increasing availability of graphic literature, a form that has evolved out of the simple comic book, learners who are more visual than verbal are likely to derive greater enjoyment through pictorial representations, which are often in themselves engaging and amusing.

To conclude, much of the available research on the use and purpose of humour in the classroom has tended to focus on the teacher as the “generator” of humour. Discussions have tended to place the responsibility squarely on the teacher for choosing the time and occasion for introducing humour, as well as for determining the appropriate content and tone.

I have taken a different approach. Rather than require the teacher to be the occasional stand-up comedian with the needed aplomb, or a repository of quips, anecdotes, and one-liners, I believe that the teacher is in a better position to provide the right stimulus and guidance for students to discover their own instinct for a humorous take on things. A change in perspective (as in the personal story of a newly hatched chick) provides the momentum to generate humour, even as students learn the science of the phenomenon. Many history teachers incorporate the ever popular comic strip, or political cartoon, with its inherent humour, to show varying viewpoints of commentators on historical events and individual historical personalities.

In my approach, students become actively engaged in creating and appreciating the value of humour in the learning process. The teacher plays an important role in guiding them, by setting suitable assignments and tasks, taking care to define the scope of each activity. As students come up with expressions of their developing comic vision, the teacher will have the responsibility to moderate the content and tone of what students consider humorous, providing the guidance so essential to ensure that humour enlivens without turning sour. Ultimately, in the use of humour as in everything else, learning gains when it is consciously designed to be student-centred.

The author is an educator and writer with significant experience teaching at secondary and tertiary levels. She can be reached at papukamakshi@gmail.com.

Related articles

Laugh out loud… with affection

Adding fun to learning

Chase those fears with the funnies!

Why we need humour

Ha, ha, ho, ho, he, he