Usha Raman

Sixty-four years after independence, it is clear that the public education system has failed to deliver on its promise of universal primary education. The promise, restated in a global forum in Dhaka in 1996, had not lacked commitment from different stakeholders, but enmeshed in the contradictory flows of political ill and action, had in the intervening decade, lost some of its force.

Sixty-four years after independence, it is clear that the public education system has failed to deliver on its promise of universal primary education. The promise, restated in a global forum in Dhaka in 1996, had not lacked commitment from different stakeholders, but enmeshed in the contradictory flows of political ill and action, had in the intervening decade, lost some of its force.

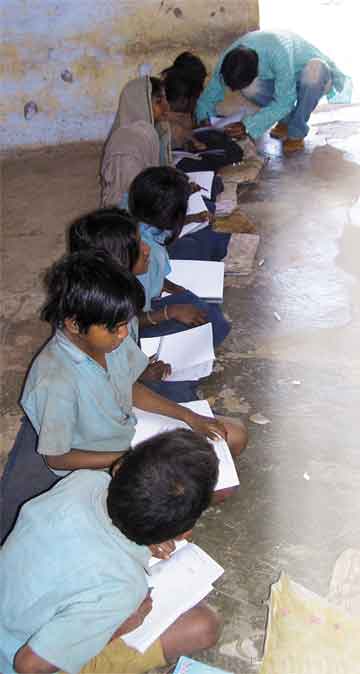

The start of the millennium saw a new movement emerge, with several groups outside the government sector begin to get seriously interested in public education, having come to the realization that one of the major reasons for the uneven development across the country, despite the material gains accrued from liberalization, was a weak education system. So now, across India, in the remote Andhra villages around Rajam, in the schools of the fledgling State of Chattisgarh, or again, among headmasters in the Baran district in Rajasthan, a new energy is at play to help influence the pace and direction of public elementary education in the country.

Of course non-government or non-state actors have always been part of the education sector, ever since the first gurukulam. But we’re not talking about a few foundations or philosophically charged organizations establishing model schools, or even about large business houses exploiting the demand for schooling among the socio-economic or cultural elite, or even well established philanthropies like the Tata trusts that have for decades attempted to support education in different ways. This new movement represents an entry into the fabric of the system, an effort to understand it inside out, and work with it, from within it.

One might argue that even this is not really new. The early 1970s saw the emergence of Eklavya, and other such experiments aimed at government schools particularly in rural areas, recognizing the severe capacity crunch in this space. As Nachiket Mor, President of the ICICI Foundation for Inclusive Growth notes in a report on the Indian Public School System, (http://www.icicifoundation.org/ downloads/india_schools.pdf), “Education is one of the most complex and challenging areas in the development sphere”. And development is at heart a public program, no matter how closely and deeply it engages people in the non-state sector.

The first decade of the new millennium has thus seen an intensifying of the effort to bring back a focus on the responsibilities of the government in elementary education, and driving this effort are a number of small, large and mid sized corporate funded nongovernmental organizations. This marks a major shift from the earlier model of corporate funding (viewed as philanthropy) that helped pay for the education of disadvantaged children, or provide books, build infrastructure or institute scholarships. Those working within corporate structures while feeling the need and the urgency to engage with larger questions of development also felt dissatisfied with the “doing good by giving” paradigm.

Education as a key to development

The financial success of many companies in the post liberalization era led some of them to think seriously of their larger responsibility to the country’s development. The ICICI Foundation for Inclusive Growth began looking seriously at involvement in key sectors such as health and elementary education. “We realized we were being seen as a responsible corporate entity, with no ideology and a certain neutrality, with a focus on building an evidence base for anything we undertook,” explains Vidhya Muthuram, Project Director at the Foundation, speaking about the genesis of the Foundation’s work. Dr Sudhanshu Joshi, President of the Foundation’s elementary education arm, adds: “Public education is the only place where you can address issues of equity and reach, and it was clear that this was where our efforts would be best placed.”

“We began asking ourselves whether our only existence was as a for-profit entity, doing business for the sake of business,” explains Anurag Behar, Wipro’s Chief Sustainability Officer and one of the leaders of Wipro’s engagement in the social development space. “And we came to the conclusion that we needed to take on a larger role in society.”

“We took some time to think through where our efforts could have the largest multiplier effect,” Behar continues. Further brainstorming pointed to education: “It seemed to resonate with us, and this came from our own experience with human resources – it appeared that schooling in our country had systematically destroyed some our most valuable skills – working in teams, problem solving, etc. In short, from any standpoint, true quality in education just did not exist.”

For the GMR Varalakshmi Foundation, part of the Bangalore-based GMR Group, choosing education as an area to engage with was practically a “no brainer”, according to Meena Raghunathan, Director-Community Services. The Group businesses take them to remote rural areas where the gaps in public services were particularly glaring, and the Foundation follows.

Sharat Vasireddy, Director-Education at Dr Reddy’s Foundation agrees. “Education is fundamental; lack of education is the reason for many things, poverty, ill health.” For the Foundation, therefore, involvement in education was seen as essential to correcting socio-economic imbalances. “It was a paradigm shift in thinking – people did not remain uneducated because they were poor, but they remained poor because of a lack of education.”

In a sense, this resonates with the larger shift in thinking toward the “causes of causes” of inequity and social injustice, tackling basic issues such as education, livelihoods and health as the root causes of poverty.

Rohini Mukherjee, Head-Policy and Advocacy of Naandi, an NGO based in Hyderabad, explains, “We felt that of all the things we could do with the funds we had, working with children was the most gratifying – you can see the results in a very short time.” At the time Naandi began working in primary education, the government was also beginning to open up avenues for collaboration with non-state actors.

The brainstorming within Wipro also led to the realization that in a sector like education, it would take years for any fundamental change to happen. “We decided then that our engagement would have to be long term,” explains Behar. “We did not want to do this in a funding mode – we wanted to work closely with the sector, more like an equity partner.”

This decision to go beyond the “fund and forget” model of philanthropy and delve into the social sector with more than money is mirrored at other large NGOs such as Naandi, Pratham and ICICI Foundation as well.

Different models of engagement

Clearly, the education of the country’s children – particularly the 8 million who are outside any system of schooling, despite the rise in gross enrolment ratios – is something that demands immediate attention and action. While some corporates, most recently the Bharti Foundation, have decided to set up their own schools to reach disadvantaged children, a smaller but increasingly vocal group believes that the only way forward is to join hands with the government.

Dr Reddy’s Foundation (DRF) began their work with children who were not in school, setting up systems to get children off the street and into safe environments. “Our initial work was with those who had missed being in school,” says Vasireddy. “Then we gradually adopted a child rights perspective, within which it was clear that school was the place for all children.” DRF decided the way to go about it was to establish model neighbourhood schools for children from all backgrounds, with an emphasis on bringing in those outside the system. “We believe that a common school system is the way to go,” says Anuradha Prasad, Chairperson of DRF. The Foundation has been engaged in advocacy at the state level, trying to bring the idea of common schools into the mainstream education discourse. DRF has been developing curricula, building resources and training teachers to fuel its own system.

The GMR Varalakshmi Foundation too has established schools in areas where the company’s work takes them. “Some of our businesses are in some of the remotest parts of the country,” notes Meena Raghunathan. “Quality schools are missing, and building schools was one way to support development in these areas.” The Foundation does not actually run these schools; it creates the infrastructure and partners with established educational groups who take over the responsibility for the management. At the same time, working with the government schools is very much part of the agenda. “There are no two ways about the fact that primary education is essentially in the purview of the government,” emphasizes Raghunathan. “In the rural areas, we work closely with the Balwadis, and government schools, supporting them with Vidya volunteers, teacher training and after school tutoring for the children as our part in supporting government schools.”

But others, like Dr. Joshi, believe that “parallel systems” of schooling are “a bridge to nowhere”. The ICICI Foundation for Inclusive Growth firmly believes that the government must be the prime provider of elementary education for the masses and non-state involvement must work only to strengthen the public system. Says Vidhya Muthuram, “It’s been a guiding belief that the government has the best intentions, but faces challenges in capacity to deliver – and that is where we can try to make the difference.” The Foundation therefore has been working closely with the District Institutes for Education and Training (DIET) in Rajasthan and with the government of Chattisgarh, among others, to provide support in infrastructure creation, leadership development, and teacher empowerment, and of course to inculcate a sense of accountability.

This word – accountability – has a special place in school education today. Much of the emphasis in these efforts to transform education in the country has to do with putting into place a mechanism to make government institutions accountable to the communities and individuals they serve. “Some of this is because of the funders’ insistence on looking at outcome measures,” says Rohini Mukherjee of Naandi. “But the important thing is, we aren’t carried away by numbers, but are paying attention to issues like learning outcomes, effectiveness of teacher training in terms of student learning, and so on.” Her colleague Dr. Preetha Bhatia, who has for the past decade been looking at learning outcomes in government and small private schools, also notes, “There is a real shift toward focusing on the child, and what he or she is learning – not just whether she is going to school or not.”

For Naandi, the engagement derives from a realization that education requires funds (which come largely from the government and a small percentage from foundations and corporates), efficient implementation, and effective monitoring. “Naandi decided we did not want to be an implementing agency – that role belonged to the government,” says Mukherjee. “So what we do is build models and demonstrate their efficacy, and then leave it to the government to scale up.” The Naandi midday meal scheme, based on a centralized, modern kitchen for a given geography, has been one of those successes. Now they are moving into school management and teacher training for public school systems in areas as diverse as the slums of Mumbai and rural Chattisgarh. The most recent initiative has been in helping turn around poorly performing government schools.

Wipro’s model of engagement is different. “We realized we knew little about this space, so we decided to look for and support organizations that were already deeply involved in reforming education,” says Anurag Behar. “So we helped build capacity, create networks, and tried to build a knowledge base of good practices in education. And ultimately, see if we could leverage this for advocacy in the sector.” In this direction, the “Wipro Applying Thought in Schools” (WATIS) initiative has focused on working with a diverse set of organizations ranging from Ekalavya in Madhya Pradesh to EZ Vidya in Chennai to Digantar in Udaipur, to help them build capacity and in the process, create a network of knowledge and support.

No matter what the scope or design of engagement, there is a palpable excitement and energy about these individuals and organizations when they talk about their work. Contrary to the widely held conception of the government as slow to move, reluctant to change, and resentful of new ideas, when Mukherjee, Joshi or Raghunathan talk about their interactions with the government there is a clear sense of hope. “Everywhere we go, we find teachers who are doing excellent work despite all the constraints they face, and there are village headmasters who are committed to their schools,” says Joshi, having recently returned from an interaction with over 70 stakeholders in Baran district of Rajasthan. Adds Rohini Mukherjee, “We are continually meeting bureaucrats who want things to change and who are very willing to listen to us.”

Realizations and rewards

“I think we’ve managed to make significant progress over the past few years,” says Anurag Behar. “Clearly, there is a new crop of decent organizations working in education, and people have understood that quality of education is a bigger issue than access.”

That quality has entered the discourse in a major way is due in part to organizations like Pratham and later, Education Initiatives, which through their assessments showed that children in schools – both public and private – were not performing. “Now, we have mechanisms that allow us to measure outcomes, and then to hold government institutions accountable for delivering on quality,” says Mukherjee.

These organizations have not stopped at creating a culture of accountability; many are providing support that enables teachers and public school systems to deliver. Says Meena Raghunathan, “We’re finding that with the right kind of support, teachers are responding, they are enthusiastic about focusing on learning.” Preetha Bhatia also emphasizes, “The majority of government teachers are motivated and committed – they have not had much direction so far, and with the kind of involvement we are bringing in, good things will happen!”

But those who continue to focus on access also see the need for ongoing advocacy and expansion in this area. “We have seen a direct outcome of our work in policy,” notes Sharat Vasireddy, referring to DRF’s work with children from displaced families. “For instance, in how children from migrant labour families are viewed by the education system has changed now.”

Next step: collaboration for critical mass?

Next step: collaboration for critical mass?

Given the size and acknowledged complexity of the sector, it is difficult for any of these initiatives singly to make a big dent and achieve widely demonstrable results. And given the culture of corporate working, collaboration is neither easy nor natural. But is it even necessary? On the face of it there is a lot of duplication in effort across corporate-led NGOs. Each has its own education resource centre, its curriculum development group, and its advocacy cell.

“Well, you have to accept that as an organization you may not have all the solutions, but there is a sense of corporate branding to each effort,” says Vidhya Muthuram.

“But this (lack of cooperation) is a malady that does exist in the NGO sector,” admits Behar. “There are areas where collaboration would be of advantage – the Azim Premji Foundation’s extensive experience in pedagogy for instance could be put to use by NGOs that are running schools.”

Rohini Mukherjee feels, given the diversity of approaches to teaching and learning even among academics, it is difficult to expect cooperation at the implementation level. She does note that a certain complementarity might be achieved across tasks in this space, and certainly, cooperation can help advocacy. Says Vasireddy, “Schools have to become non-sectoral spaces, with learning seen as a neutral issue – then collaboration could be meaningful.”

For those of us who believe that the government must be the main provider of essential services, that our tax rupees must be put to the uses they are meant for, it is heartening to know that things are happening in a manner that strengthens this system. Says Joshi, “Our effort is to demonstrate that in India we have one of the best infrastructures for developing quality, there is scope for innovation, and given a bit of independence, and the right material and intellectual inputs, we can embed quality in the system.” The government, for its part, seems to be open to ideas, to inputs, and to allowing its hand to be held by those who offer strength in this very crucial area.

Taking responsibility for education

Is Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) charity or philanthropy or is it merely a business strategy? While an answer to this question may prove to be a little difficult and one can speculate on the motives and intentions of donors, what is clear is that corporate India has taken initiatives to make society more inclusive and sustainable.

The tradition of giving has long been associated with Indian culture, being strongly embedded in the psyche of Indian families. Viewed mostly as charity, this has moral and religious overtones. Philanthropy, on the other hand, has taken on a larger dimension. Indian companies are now expected to discharge their obligations towards society along with maximizing profits for their stakeholders.

Although CSR as a concept has evolved recently with the Central Government even developing a system of credits to be given to companies for their initiatives, not many know that ever since Independence, the Tatas and the Birlas had already shown the way by investing their personal wealth for the greater good of the society.

Now, of course, nearly all leading corporates are involved in programmes like health, education, empowerment of the weaker sections, creation of livelihoods and many more. Notable efforts have come from the Mahindras, Infosys Technologies, Bharti Enterprises, Wipro, the Ambuja Group and several others. A quick glance at some of the websites of leading Indian companies revealed that Education topped their list of Corporate Social Responsibility initiatives.

Listed here are a few leading corporates whose initiatives in School Education are worth mentioning.

- Mahindra and Mahindra: http://www.mahindra.com/socialinitiatives/corporate-social-responsibility.html

The KC Mahindra Trust was founded in 1953 to promote literacy and higher education. The Group runs three schools primarily for the children of its employees. The schools are in Malad, Mumbai, Zaheerabad and in Khopoli. The teachers are qualified and also regularly undergo training. - The Murugappa group: http://www.murugappa.com/community/overview.htm

The AMM Foundation founded in 1953 is a charitable trust and its community initiatives are in the field of education and health. The Foundation runs four schools with state-of-the–art facilities, an affordable fee structure and constant review of all its schools. The schools are the Sir Ramaswami Mudaliar Higher Secondary School, the Vellayan Chettiar Higher Secondary School, the TI Matriculation Higher Secondary School, and the AMM Matriculation Higher Secondary School. - DLF Building India: http://www.dlf.in/dlf/wcm/connect/dlf_common/DLF_SITE/HOME/TOP+LINK/CSR/CSR+Initiatives

DLF or Delhi Land and Finance is one of the largest real estate companies in India and has helped accelerate the pace of social and economic growth. According to its Chairman, Mr. KP Singh, “For DLF, CSR is not just an add on, our business and social commitment is mutually reinforcing and neither is sustainable without the other.” The DLF’s first social initiative was the setting up of Swapana Sarthak informal schools for the children of construction workers. DLF along with Pratham, has also set up Learning Excellence Centres in 25 villages in Haryana involving government schools, community teachers and introducing innovative teaching learning material. This is an ongoing project. - The Bharti Foundation: http://www.bhartifoundation.org/wps/wcm/connect/bhartifoundation/BhartiFoundation/Home

The Bharti Foundation is the philanthropic wing of Bharti Enterprises and was started in 2000 to help underprivileged children across rural India. The Satya Bharti School programme reaches out to nearly 200,000 children and the goal is to establish 500 primary and 50 senior secondary schools. - ICICI Foundation: http://www.icicifoundation.org/elementaryeducation-10.htm

The ICICI Elementary Education Programme under the aegis of the ICICI Foundation tries to improve the performance of teachers in government schools. Other initiatives include curriculum and textbook development, capacity building of government organizations, and also building partnerships and resource centres. - Jindal Steel: http://www.jindalsteel.com/

Jindal Steel runs three schools, Vidya Devi Jindal school, OP Jindal Modern School in Hissar, and OP Jindal School in Raigarh. - GMR Foundation: http://www.gmrgroup.in/foundation.html

The GMR Varalakshmi Foundation, through different interventions, works to improve teaching in government schools. Through its teacher training programmes, it trains teachers and posts these Vidya Volunteers in schools where the student-teacher ratio is poor. Other infrastructure support is also provided. - Hinduja Group: http://hindujagroup.com/hindujafoundation/default.html

The earliest philanthropic work of late PD Hinduja began in 1944 with the setting up of a charitable trust for education. The Foundation has a number of education related projects, chief among them being the Hinduja Model Sindhi secondary school in Chennai established in 1975. More information on this school can be got from www.sindhimodel.com. - Infosys Foundation: https://www.infosys.com/infosys-foundation/initiatives/education/

In its attempt towards creating a more equitable society, the Infosys Foundation has made strides in healthcare, education and the Arts. Its rural education programme is one of the largest in the country. Its Library for Every school Project is also one of the largest spreading across Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala and Orissa. Under this, the Foundation has set up more than 10,000 libraries in rural schools. - Wipro and Azim Premji Foundation: http://www.wipro.com/corporate/aboutus/corporate-social-responsibility.htm

http://www.azimpremjifoundation.org/assessmentled-reform.html

Education has been a key investment for Wipro and it has built a network of organizations committed to social reform. Likewise, the Azim Premji Foundation reaches out to over two million children in over 20,000 schools. Its Learning Guarantee Programme is a vehicle to bring about change in the way children are assessed while they learn.

The view from academia

While corporates, driven by their zeal to apply their powerful voice, their growing social conscience and a percentage of profits to the education sector, a number of academics, working in Universities and research institutions, are critically studying issues of equity and participation in this space. “Personally, I feel that private sector interventions are not entirely philanthropic, there is an underlying business interest,” says Prof. Geetha Nambissan, from the Zakir Hussain Centre for Educational Research at New Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University. In a paper entitled “Advocacy networks, choice and private schooling for the poor in India,” (co- author Stephen Ball, in Global Networks 10, 3, (2010): 324-343), she argues that certain private interests, recognizing that Indian education sector is the largest capitalized space in India, represents a ripe market for those wanting to come in with soft loans, services, consultancy and products. While her criticism is directed mainly at the pheonomenon of “Affordable Private Schools”, low cost private schools aimed at lower socio-economic groups that have lost faith in the government school system, she also emphasizes that the rhetoric of quality brought in by the corporate sector as a whole sometimes deflects from the basic issue of access in its truest sense. “The way they are redefining education is somewhat problematic,” she says, pointing to the emphasis on outcomes, and suggests the need for a “debate on the long-term effects of different types of engagements.”

Dr. Rajeev Sharma of the Ravi Matthai Centre for Educational Innovations at IIM-Ahmedabad, is more positive about corporate involvement in this space. However, he is quick to clarify that he believes that the effort should be limited to strengthening the government’s hands rather than build a parallel system. Citing examples like the Kaivalya Education Foundation’s leadership development program through the Gandhi Fellowship, or Pratham’s ASER reports, he says that the new energy brought in by such initiatives has begun to transform the public education system. “The magnitude of the task of reforming government schools is so large, that a single actor cannot handle it,” he explains. “Nowhere in the world can (primary) education be handed over to the private sector,” he continues. “But we do need to experiment with different models of cooperation and collaboration among different groups, and then review the experience critically.”