Sridhar Rajagopalan and Nishchal Shukla

India has agreed to participate in PISA in 2021. A small number of randomly selected students from Chandigarh, the Kendriya Vidyalayas and Navodaya Vidyalayas will write the test next year.

India has participated once in PISA before, in 2009-10, when students from Tamil Nadu and Himachal Pradesh wrote the test. We performed very poorly, ranking 73rd among 74 countries, finishing ahead of only Kazakhstan.

This result was shocking and many people assume that it must have been an aberration. Maybe the students were not prepared for the test or had to take it in English. (Actually, all students were tested in their medium of instruction.) Maybe only government schools were tested – our private schools would have done much better. (A detailed study conducted by our organization in 2006 and repeated in 2012 established that students of our top private schools perform below international average in class 4.)

Our organization regularly conducts assessment for private schools (called ASSET) as well as for various governments. These assessments (as well as tests like Pratham’s ASER) seem to suggest that we do indeed have a learning crisis in our system. Our learnings and conclusions based on doing such assessments for about 20 years in India are:

- From a learning perspective, India’s education system is very poor – in our analysis falling behind even some of the poorest performers in Africa.

- For India to improve its education system, it needs to a) ensure strong foundational language and arithmetic skills by class 5 and b) have a school leaving exam (board exam) focussed on learning and not simply recall.

What is PISA and can it be more than just a harbinger of (bad) news? Can we learn from assessments like PISA (and good assessments we already have in India) to improve our assessment systems, including our board exams at which all teaching is targeted? In this article, we shall look at what PISA is, delve into its mathematics testing framework in some detail and examine how we can use it to actually improve our learning levels. Since the main problem with our board and school exams today in the poor quality of their questions, we shall take examples from PISA and some other questions and explain why good questions are so critical to attain good learning.

PISA, the Programme for International Student Assessment, is an international benchmarking test that assesses random samples of 15-year old students (typically in class 10) on their reading (language), mathematical and scientific literacy skills. It has been conducted every three years since 2000. A country (or region) must voluntarily agree to write the PISA test. Another international assessment, TIMSS (Trends in International Mathematics and Science Studies) is similarly conducted once every four years for students of classes 4 and 8 since 1995. India has participated only once (2009-10 in PISA) among all these and a few other assessments.

Assessments like PISA and TIMSS have shown that some countries like Singapore, Finland and South Korea have been among the top performers though ranks vary a bit between the years and the assessments. China has been a late entrant but has performed extremely well with Shanghai city topping the PISA in recent years. The US is an example of a country that has spent a lot of money but has performed only at average levels in benchmarching tests since the 1990s.

PISA mathematics – skill framework and types of questions

The PISA tests “are designed to gauge how well students master key subjects in order to be prepared for real-life situations in the adult world.”

The test contains items from three core domains – reading, mathematics and science. In each round, one of these is the major domain. PISA 2021 will have mathematics as the major domain. This means that there will be more assessment items in the papers assessing mathematical literacy.

The PISA Draft Framework defines mathematical literacy as:

“An individual’s capacity to reason mathematically and to formulate, employ, and interpret mathematics to solve problems in a variety of real-world contexts. It includes concepts, procedures, facts and tools to describe, explain and predict phenomena. It assists individuals to know the role that mathematics plays in the world and to make the well-founded judgments and decisions needed by constructive, engaged and reflective 21st century citizens.”

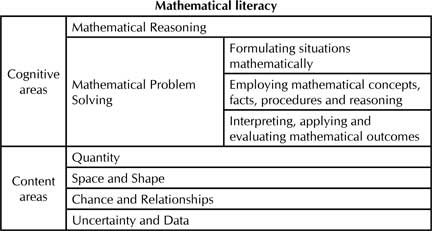

It assesses the following cognitive and content areas.

So what differentiates a PISA question from other questions and why do students struggle on PISA questions?

PISA questions require students to a) understand the information provided, b) find what needs to be determined or solved and then c) apply the appropriate procedure. The questions we use in our Indian tests (including board and school exams) tend to be based on a small number of familiar question types. Thus only c) in the above list is tested. That was probably okay for the well-defined world of the 1950s and 60s, but in today’s circumstances, the ability to absorb new information and define the problem and choose what needs to be solved, is even more important. Let us look at a few PISA and our own PISA-like questions from ASSET to understand this:

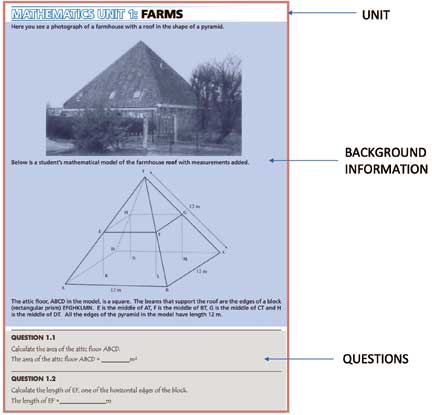

Sample PISA Questions – Mathematics

The purpose of the background information in such questions is to provide a real-life context to the student based on which the questions are asked. That information can be of different types and cover a variety of contexts.

| Different types of background information possible: | Variety of contexts background information may cover: | • passages | • personal (individual, peer group, family) | • tabular information/data | • occupational (the world of work) | • images | • societal (local, national or global community) | • graphs or charts | • scientific (natural or technological world) | • combinations of the above | • some more advanced types of materials involve interactives that PISA uses for computer-based tests |

Importance of good questions and challenges students face

While one may point out that the context used may be unfamiliar and may cause students to struggle to answer the question, it is important to note that this is one of the characteristics of a good question. Many other international assessments including TIMSS and our own ASSET test use questions that are based on unfamiliar contexts or which appear as if they are not something students are used to answering.

For example, consider the following question from ASSET.

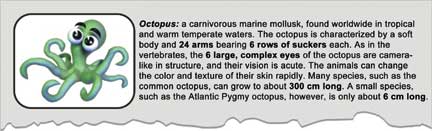

Hiten typed in a paragraph about octopuses for a project. His sister Nandita played a prank and changed all the numbers in the paragraph by multiplying each correct number by the same number, say ‘n’.

Now Hiten has to correct the numbers again. What should he put as the actual length of the Atlantic Pygmy octopus? (Hints are given in the visual of the octopus.)

A) 2 cm

B) 3 cm

C) 6 cm

D) 18 cm

Source: ASSET – https://www.ei-india.com/asset

The question uses a factual piece of information and gives the context of what happened when someone changed the numbers in the factual piece in a certain way. Students are expected to understand this context and use one piece of knowledge that they are familiar with regarding the correct number of arms an octopus has, to solve the problem and answer the question. In fact, even if they don’t know that fact, they can take hint from the image given. While a lot of students may find answering this kind of question interesting and the process enjoyable, the first reaction of many teachers is that this is ‘out of syllabus’ and so students cannot be expected to answer it. In our sample of around 14000 private English medium school students, only 21.5% students were able to answer this question correctly. 31.1% students selected option D, indicating that they didn’t really understand the context and the question and blindly selected the length (incorrect) mentioned in the passage.

It is important to note that the data for the two questions above are from students of private English medium schools whose performance tends to be higher than those of government school students. A large percentage of government school students often struggle in the first step itself, in reading the given text.

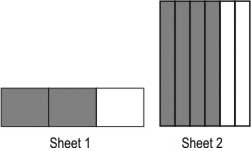

This argument that students fail to answer due to lack of familiar context fails when we look at their performance on some of the basic conceptual questions like the one that follows. This question was given to the same 14000 private English medium school students. Only 30.7% students were able to answer this question correctly. 27.7% students selected D indicating that they were just used to calculating area of such shapes given their dimensions and could not think beyond that procedural knowledge.

Two sheets of different sizes were shaded as shown.

Which of the following is equal for the two sheets?

1. Area of the shaded part.

2. Percentage of the sheet shaded.

3. Ratio of the shaded area to the unshaded area.

A. only 2

B. both 1 and 2

C. both 2 and 3

D. Can’t say unless the dimensions of the sheets are known.

Source: ASSET – https://www.ei-india.com/asset

As seen in the above two examples, a good question is one that challenges and stimulates a child to think deeply and to apply concepts learnt. A good question, correctly framed, can help a teacher understand the thought processes of students and how well a child has internalized a concept or mastered a skill.

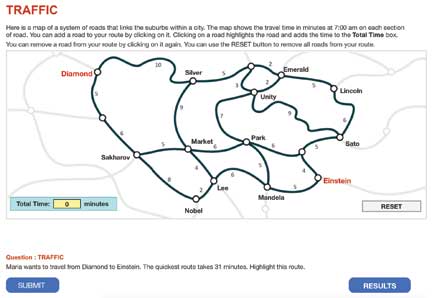

Interestingly, a majority of the countries do the PISA test on the computer. The computer-based version of the test includes MCQs (Multiple Choice Questions) as well as other technology-enhanced item (TEI) types. TEIs typically help elicit responses that otherwise are difficult to do in a traditional MCQ or even a free response question format. Here is an example of one such question that allows students to interact with the map, select/deselect a route and check the time taken to travel through the selected route. It then asks a question that uses this interactivity. The advantage of such a question would be that it would capture not just the final answer (which an MCQ could also have) but also what the student selected, the sequence in which selected and the time taken before the student answered the question.

Interestingly, a majority of the countries do the PISA test on the computer. The computer-based version of the test includes MCQs (Multiple Choice Questions) as well as other technology-enhanced item (TEI) types. TEIs typically help elicit responses that otherwise are difficult to do in a traditional MCQ or even a free response question format. Here is an example of one such question that allows students to interact with the map, select/deselect a route and check the time taken to travel through the selected route. It then asks a question that uses this interactivity. The advantage of such a question would be that it would capture not just the final answer (which an MCQ could also have) but also what the student selected, the sequence in which selected and the time taken before the student answered the question.

Due to the advantages listed above, the use of TEIs in assessments is increasing. Even ASSET’s computer-based version tests students on MCQs as well as TEIs.

Conclusion

Tests like PISA help at multiple levels. While the benchmarking data they provide may serve as a wake-up call, probably even more important is the learning from the type of questions these tests use. If used correctly, a good question can prove to be a highly effective tool in the process of learning and can even enable learning. In that sense, studying tests like PISA and our own tests like ASSET is something every teacher must do. While developing questions like these improve the capacity of teachers, analyzing the student performance shows how children are thinking and the errors they are making. Understanding these and modifying our teaching methods accordingly may be the best way to move towards improved student learning.

Sridhar Rajagopalan is co-founder and Chief Learning Officer of Educational Initiatives Pvt. Ltd. He can be reached at sridhar@ei-india.com.

Nishchal Shukla is Associate Vice President, Pedagogical Research, at Educational Initiatives Pvt. Ltd. He can be reached at nishchal@ei-india.com.